Details

Name: Belfast Celtic

aka: Grand Old Team

Founded: 1891

Closed: 1949

Reference: Ulster based football club playing in IFA league closed down due to sectarian attacks.

Note: Since the closure of Belfast Celtic, certain other local clubs have started or rebranded themselves as ‘Belfast Celtic‘, some even claiming they are a successor or continuation of the old club. However, The Belfast Celtic Society group who have played a leading light in keeping the memory alive of the old club have made it clear that “Its heritage is not for anyone else to acquire or purloin“, and “no claim can be made to the history of the original Belfast Celtic… no matter how tenuous their connection with Belfast Celtic“.

The History of the Grand Old Team from Belfast

(following is taken from a Not the View article: see: link, but the article has been edited by TheCelticWiki contributors for updates & to include further information)

At the foot of the Donegal Road in Belfast there stands a bright, modern shopping complex. But for those old enough to remember, it will always evoke a certain sadness, because the shops were built over the site of Celtic Park – ‘Paradise’ to the faithful – for 58 years the home of Belfast Celtic.

The club was formed in the summer of 1891 and the first Chairman, James Keenan, provided the first and only suggestion for a name, Belfast Celtic.

The origin of his choice stemmed directly from Glasgow Celtic, then three years old, and the Belfast men realised that they would have to live up to all its expectations. The chairman added that the purpose of the team would be to “imitate their Scottish counterparts in style, play and charity” but their main aim was to win the Irish Cup! The ethos of (Glasgow) Celtic was what they wished to replicate in Belfast.

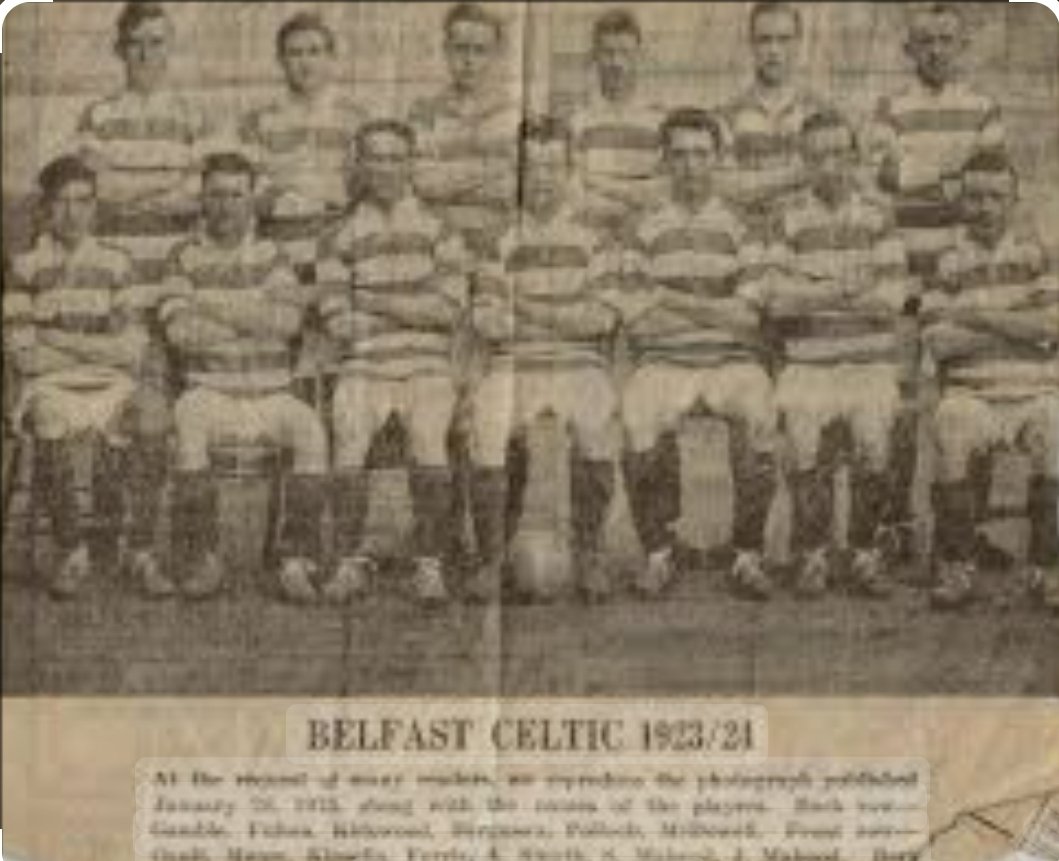

They didn’t have long to wait before they won their first league title, which came in season 1899-1900, the first of fourteen leagues and eight Irish Cups. The club became an institution on the Falls Road and in the Twenties they were certainly the team to beat. At one time Belfast Celtic had five international goalies on their books at the same time, and no international select was complete without two or three Belfast Celtic players.

Celtic & Belfast Celtic together had a very healthy relationship with numerous players having played for both clubs, including the great Charlie Tully, Willie McStay and Mickey Hammill. Friendly matches were also organised and played between the sides to cement the relationship. Curiously, all the matches were played in Belfast and not once at Parkhead.

Of interest to all Celtic fans is that the origin of the Celtic anthem “Hail Hail” is likely from Belfast. In a 1927 Belfast Celtic programme the words are given to the tune beginning: “What a grand old team to play for” and ending “And the Belfast Celtic will be there“. Some put it down to Charlie Tully having popularised the song in Glasgow on his transfer over, and is a wonderful gift to the Celtic support and all should remember Belfast Celtic for a moment when they hear it.

Towards the end of the First World War, Belfast Celtic had broken most of the records in Irish football and things seemed set for continued domination after World War II, until disaster struck in 1948. Unlike their local rivals Linfield, Belfast Celtic were never a sectarian club, but the fact that they and the majority of their supporters came from west Belfast meant that derby matches were inevitably fraught with tension.

Society was changing, their island was now divided and tensions were deepening between the differing communities in Belfast.

Until Boxing Day 1948, terracing violence had never affected the players, but on this day that was all about to change.

Notably, the Belfast correspondent of the Irish Times reported that police moved through the terraces with batons drawn to try and stamp out any disorder before the game began. Not a good sign.

As for the match, the Belfast Celtic v Linfield game had been a scrappy affair, with a player from each side being sent off. But the storm broke ten minutes from time. With Linfield leading by a goal to nil Celtic were awarded a penalty. As Walker stepped up to take it hundreds of Linfield supporters rushed on to the pitch and attacked some of the Belfast Celtic players, resulting in a broken ankle for one of them.

Rumours that Belfast Celtic were going to withdraw from the league were soon confirmed, and Belfast Celtic ceased to grace the competitive scene at the end of the 1948-49 season. Thereafter they played only exhibition games, one of which was against the Scotland national team, which Belfast Celtic won by 2:1.

After this tour Belfast Celtic ex-stars came together just twice more. The first occasion was an emotional match at Celtic Park on 17th May 1952 against Glasgow Celtic, whose team included ex-Belfast Celtic man Charlie Tully and the great Jock Stein. Note that for this game (Glasgow) Celtic were actually playing a Belfast Celtic Select who played under the banner of Newry Town (a team affiliated to the Irish League). For the record: (Glasgow) Celtic won 3-2.

It has been widely agreed that, since the departure of Belfast Celtic, Irish club football has generally never recovered from the loss. The fighting spirit seemed to go out of the game and attendances sank dramatically.

Every Irish football fan wanted to see the Belfast Celtic because they knew they would see football at its best. There are no such events now, no crowds and no local club team even remotely similar in style. The club game in Northern Ireland is dying and has been since 1949, despite some grand stands at the international level.

In any history of Irish football there will be a chapter devoted to the glory and triumph of Belfast Celtic, 1891-1949. For it is only the glory that remains – the glory, the memories and and a shopping centre built on what was once (Belfast) Celtic Park.

It was also a warning to (Glasgow) Celtic about the rising tensions and the potential repercussions if the club didn’t manage their similar situation too. One Celtic may have gone but the other was to build on in the other’s place, and a repeat was to never happen.

The ties between the clubs have remained. In 2001, in honour of our then Northern Irish manager (Martin O’Neil) for the title clincher against St Mirren, a host of former Belfast Celtic players were invited including Jimmy Jones, Jimmy Donnelly, Leo McGuigan, Ossie Baillie, Alex Moore and George Hazlett (who actually played for both clubs). Charlie Tully Jr represented his father. A proud day for all.

Picture from the 1952 friendly to honour the late Belfast Celtic

Quotes

“After our Glasgow friends and that our aim should be to imitate them in their style of play, win the Irish Cup, and follow their example, especially in the cause of Charity.”

Chairman James Keenan suggested ‘Belfast Celtic’ should be adopted

Players & Managers to have been at both Celtic & Belfast Celtic

- Tom Barber

- John Black

- John Blair

- James Blessington (player for Celtic, manager for Belfast Celtic)

- William Crone

- Bob Davidson

- Willie Donnelly

- Patrick Farrell

- Jim Foley

- James Gallagher

- Michael Hamill

- George Hazlett

- Willie Loney

- Gerald McAloon

- Daniel McColgan

- Jimmy McColl (player for Celtic, manager for Belfast Celtic)

- Charles McGinlay

- Harry McIlvenny

- Willie McStay

- Con Tierney

- Charlie Tully

- John Wallace

- Hugh Watson

- Jim Welford

Also, Tom Colgan was on the boards of both clubs.

External Links

Matches

- 1897-04-20: Belfast Celtic 0-4 Celtic, Friendly

- 1902-04-01: Belfast Celtic 0-1 Celtic, Friendly

- 1904-03-18: Belfast Celtic 1-0 Celtic, Friendly

- 1910-12-27: Belfast Celtic 0-1 Celtic, Friendly

- 1915-01-23: Celtic 4-0 Belfast Celtic, Friendly

- 1925-04-27: Belfast Celtic 0-3 Celtic, Friendly

- 1926-04-19: Belfast Celtic 2-3 Celtic, Friendly

- 1927-05-03: Belfast Celtic 4-2 Celtic, Friendly

- 1928-05-01: Belfast Celtic 0-1 Celtic, Friendly

- 1929-04-29: Belfast Celtic 4-7 Celtic, Friendly

- 1930-04-24: Belfast Celtic 1-2 Celtic, Friendly

- 1932-04-18: Belfast Celtic 0-3 Celtic, Friendly

- 1936-04-28: Belfast Celtic 1-2 Celtic, Friendly

- 1947-04-05: Belfast Celtic 4-4 Celtic, Friendly

- 1952-05-17: Belfast Celtic 2-3 Celtic, Friendly

Articles

Belfast Celtic Museum

Sixty one years after Belfast Celtic left the footballing stage, they have returned to Paradise.

The Belfast Celtic museum opened at the Park Centre shopping complex in Belfast on Saturday July 3 2010 to commemorate and promote the history and story of the club and the sad circumstances that led to its premature closure.

The Belfast Celtic Society’s museum space was officially opened by star striker Jimmy Jones, Paddy Bonnar’s daughter Heidi Boyle and Mayor of Belfast Pat Convery.

Situated in a major unit inside the Park shopping centre, on the site of the old Celtic Park on the Donegall Road, the museum opening was tremendously received by hundreds of well-wishers and grand old fans.

Filled with memorabilia and items of nostalgia, the museum is the culmination of a major push by the Society to raise awareness on the history of Belfast Celtic. Belfast Celtic’s great rivals Linfield were represented on the day by their Chairman Jim Kerr and other Board members – and they came bearing gifts, a £100 donation to help fund the museum.

The organisers are in the throes of a fund-raising campaign to help keep it open,and so if you wish to donate then please use the ‘donate’ feature on the website below, that would be very helpful.

We wish the project all the success in the world.

More details can be found here: http://www.belfastceltic.org/

The day the mighty Belfast Celtic died

Saturday, December 27 marked the 60th anniversary of one of the ugliest moments in the history of Irish football, when severe sectarian violence spilt onto the pitch at a Belfast Celtic v Linfield match at Windsor Park. The events of that day were the beginning of the end of one of the most successful Irish football teams ever. Sports historian and writer Barry Flynn looks back….

For two teams whose grounds were less that half a mile apart, Belfast Celtic and Linfield could well have existed in different universes.

The sectarian divide kept both communities encased within their own areas, while for both sets of supporters political and religious pride was at stake when Celtic and Linfield clashed. In front of 27,000 feverish spectators, a bruising and bad-tempered encounter ensued.

By the end of the game, the teams were level at one goal apiece, and while Linfield finished the encounter with eight players to Celtic’s ten, those statistics were made irrelevant by the scenes that followed the final whistle.

One player’s name became synonymous with the events that fateful day; his name was Jimmy Jones, the bustling Celtic forward from the Co Armagh town of Lurgan.

In a twist of terrible fate, an accidental collision between Jones and the Linfield defender Bob Bryson in the thirty-fifth minute of the game, led to Bryson being stretchered off the field with a broken ankle.

Mid-way through the second half, it was announced on the public address system that Bryson’s ankle had been broken. Given the tinderbox that existed within the ground, it was, to say the very least, an irresponsible act.

In reality, Jimmy Jones was now on borrowed time as the atmosphere in the ground became poisoned and at the final whistle a section of the Linfield fans exacted shameful retribution.

The ‘Match of the Season’ that had been expected ended in a bitter and nasty display of hooliganism that was to set in motion a chain of events that saw the demise of Belfast Celtic.

Whether Irish football has recovered from that day is open to debate but it became a poorer entity after the events of 27th of December 1948.

Surprisingly, segregation was not imposed within the ground, but supporters of both sides congregated in parts of the terraces where they felt safe in numbers.

The most vociferous of the Linfield supporters gathered on the extensive Spion Kop terrace which overlooked the goalmouth at the Bog Meadows end of the ground. It was from this area that the trouble was to later originate.

Celtic fans were housed in significant pockets around the ground, but they kept away from the unruly elements among the home fans.

Given the festive season, there could be no doubt that a significant number of supporters had ‘drink taken’ before the match and many came with bottles to fortify themselves against the cold.

A small detachment of RUC officers patrolled the ground and kept their eyes on the spectators but nothing untoward was expected that December day.

By 1.30pm the ground was filling up and as usual the ‘party songs’ began, it was reported, mainly among the home fans on the Spion Kop end of the ground.

The Belfast correspondent of the Irish Times reported that police moved through the terraces with batons drawn to try and stamp out any disorder before the game began.

Both teams were afforded a typical ‘Windsor welcome’ from the fans as oaths and insults rained down from the enclosures. The signs were ominous as referee Norman Boal blew his whistle in the cauldron that was Windsor Park.

The game kicked off at 2.30pm and Linfield were the first to show and forced two early corners which the Celtic defence had difficulty dealing with. The visitors soon gained their composure and George Hazlett and Johnny Campbell led the attack, while Jones came close to opening the scoring on twenty minutes.

The game intensified and the tension in the ground rose considerably as rain began to fall and the light began to disappear. Ten minutes from the interval, the crowd erupted as a clash between Jones and Bob Bryson saw the Linfield defender writhe in agony as a stretcher was called for to take him from the field.

The incident arose when Jones fouled Bryson and as the Linfield player went to kick the ball at his opponent the crack of Bryson’s ankle was heard across the ground. Bryson had caught Jones’ foot with his own ankle and received a bad break.

Tempers on and off the pitch became frayed and referee Boal was forced to caution a number of players, while the police were again forced to go on to the terraces to break-up some scuffles.

The net result, given that no substitutes were then permitted, was that Linfield were now down to ten men and at a disadvantage as the game approached half-time.

Shortly afterwards, Linfield forward Jackie Russell was pole-axed and taken from the field after he had been hit full-on by the football and as the whistle blew for the break, Linfield had only nine fit players on the field.

The opening forty-five minutes had laid the foundations for the chaos to come. The ground possessed an undertone of serious violence and sectarian hatred was bubbling below the surface.

When Linfield announced over the public address system that Bryson’s leg, rather than his ankle, had been broken, the genie was most certainly out of the bottle.

This act of folly shortened considerably the odds of a backlash against Jones and the Celtic players. Why they felt the need to do this has never been resolved but it was, at best, totally irresponsible in the circumstances.

The game resumed in gathering darkness with Linfield still two players short. Russell had been sent to the Royal Victoria Hospital with severe bruising, while Bryson had a broken ankle.

Undeterred, the Linfield supporters willed their team to keep the Celtic attack at bay with inside left Isaac McDowell starring for the Blues.

With the game poised and scoreless, the temperature reached perilous heights when Celtic’s Paddy Bonnar and Linfield’s Albert Currie were sent off after they clashed with eighteen minutes left.

By this stage, most observers felt that others on the field should have ‘walked’, but referee Boal’s hand was forced and the crowds reacted in turn.

Gaps opened up on the terraces as fighting broke out among spectators on the Spion Kop and the police again drew their batons.

Within minutes, it seemed that an uneasy calm had been restored, but with ten minutes to go Linfield full-back Jimmy McCune upended Celtic’s Jackie Denver in the box.

To the roar of the Celtic fans, Boal awarded a penalty from which Harry Walker scored. The situation was now bordering on the brink of chaos as Celtic seemed certain to take the points.

Many thousands of supporters sensed that there would be trouble and headed for the exits as the match entered its closing stages.

However, Linfield attacked in search of an equaliser and were rewarded four minutes from time when Isaac McDowell burst down the wing and found Billy Simpson in the box.

The Linfield forward made no mistake as he finished past Kevin McAlinden to square the game. Immediately, masses of Linfield fans surged from the terraces and invaded the pitch in celebration.

Celtic goalkeeper McAlinden was manhandled by the mob, while Jones and Aherne received some close attention also. The police present battled to clear the field and the remainder of the game was played out amid a deafening roar.

At the death, Linfield almost stole the game but the players’ minds were now set on making the dressing rooms as the game concluded.

The final whistle saw the Linfield mob on the Spion Kop invade the field and they began again to attack the Celtic players.

Furthest from the pavilion, at the far end of the field, was the solitary figure of Celtic’s Jimmy Jones. In addition to the ‘sin’ of being involved in the Bryson incident, Jones was targeted as he was, quite simply, a sublime footballer who had already scored twenty-six goals that season.

Add to this that he was a Protestant and to the Linfield mob he was fair game as he was also a ‘traitor’ to his, and their, religion.

Whilst many of the spectators from the unreserved enclosure were intent on congratulating the Linfield players, initial banter of Jones soon turned to abuse as members of the mob accused him of deliberately setting out to injure Bryson.

By the time Jones had made his way to the running track at the side of the pitch, the ringleaders from the Spion Kop had reached him and he was dragged over the parapet into the terrace below the main stand.

The 20-year-old was now at the mercy of the baying mob as police elsewhere tried to clear the field. In the stand watching in horror were Jones’ mother and father who had travelled up from Lurgan for the occasion.

What followed in the terrace was brutal and prolonged. Jones was trapped and hidden in a sea of bodies while the rest of the Celtic team battled through the raging crowd.

The beating was merciless on the Jones. He was punched in the back of the head. However, as he tried to make his way up the terrace away from his attackers, he was tripped and dragged back down the steps.

The core of the mob now consisted of about thirty men and unhindered they set about the prostrate Jones.

The attackers knew what they were doing and immediately began to jump on the legs of the player to ensure maximum damage was inflicted on his career.

Heavy hob-nailed boots danced on Jones’ leg and ankle as the frenzied crowd took turns to jump on the hapless player. He was kicked around the terraces like a rag doll.

After what seemed like an age, a police constable arrived and tried to intervene.

Immediately, he shouted at the mob, ‘If you don’t stop kicking him I’ll use my baton!’ Not surprisingly, he too was beaten back as the attack continued unabated.

Meanwhile, in the pavilion, the Celtic players became aware that Jones was missing and vowed to return to the pitch to rescue him.

Celtic officials and directors calmed the players and sought help to get Jones. Despite the danger, a close friend of Jones – Ballymena goalkeeper Sean McCann – waded into the madness from his seat in the grandstand.

He wrapped himself around the screaming player, guarding his leg, which was badly mangled. Finally, a dozen police officers arrived to aid Jones and the mob dispersed post-haste. It was too late, the damage had been done and the repercussions were about to begin.

On his rescue, Jones was rushed to the Musgrave Park Hospital where surgeons fought to save his leg – to this day his right leg is an inch and a half shorter than his left.

The Belfast Celtic Board met that very evening and it is thought that the decision to withdraw from the game was taken at that meeting.

For Linfield, their punishment was not long in coming. The IFA met on 4th January and deemed that Windsor Park be closed for a month.

This meant that Linfield were forced to play two games ‘away’ at Solitude in North Belfast.

Meanwhile, the directors of Celtic noted the soft treatment afforded to Linfield and, eventually, on 21st April they forwarded a letter to the football authorities advising that the club was, after 58 years of existence, to leave Irish football for good.

Taken from ‘Political Football – the Rise and Fall of Belfast Celtic’ by Barry Flynn.

Belfast Celtic Football Club 1939/40 – Team Photograph

Belfast Celtic

Memories of Belfast Celtic reawakened as IFA tries to soothe old wounds

A groundshare between Protestant Crusaders and Catholic Newington could see football unite segregated communities

David Conn

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 23 February 2011 12.52 GMT

There looks to be nothing extraordinary in two groups of young footballers training on the gleaming artificial pitch at Crusaders’ Seaview stadium, on a freezing night in north Belfast. Yet in view of Seaview’s tired stands and ageing terraces, the session represents the green shoots of remarkable change: the Under-13s of Crusaders, once a Protestant, loyalist stronghold, are sharing their pitch with the Under-16s of Newington, a Catholic club.

Crusaders – lying second in the Irish Premiership, behind Protestant Linfield – have entered a close, formal partnership with Newington, which they hope will lead to a landmark shared stadium in a still highly segregated neighbourhood. Crusaders do not try to deny the brutal recent past, explicitly acknowledging two grim records which mark the Seaview ground. In 1979, to guard against trouble when Crusaders played Cliftonville, there were more police officers on duty – 1,900 – than had ever been recorded at a UK football match. Then on 12 January 1980 the Royal Ulster Constabulary constable David Purse was shot on duty, the only murder at a football ground during the Troubles.

“This club was a very unwelcoming place during the Troubles,” Mark Langhammer, a Crusaders board member, says. “If a Roman Catholic had walked into our bar just 10 years ago he would have been shot dead.

“North Belfast is still very divided but through the two clubs’ alliance we have held mutual respect sessions for the youth players, anti-racism and suicide awareness. This area, because of the sectarian troubles, has Europe’s highest rate of suicide for young men. We are looking to build a partnership, bringing people together through football.”

The Crusaders and Newington initiative is at the visionary end of wider efforts by the Irish Football Association to steer the game out of the sectarian divide, with which the IFA, predominantly Protestant, has long been associated. The governing body began its Football for All programme 10 years ago, after Neil Lennon was relentlessly booed by a loyalist section of Northern Ireland fans in a 4-0 defeat by Norway. The date, 27 February 2001, is etched into the memory of Michael Boyd, the IFA’s head of community relations, then fresh out of Ulster University and new in his post.

“That was a catalyst to tackle sectarianism,” Boyd says. “It was a big moment, when many people involved in football decided they wanted better for the game.”

The IFA began to pursue a culture change, despite being widely mistrusted then by many Catholic football followers, who still resent the IFA’s staggering 100-year agreement, signed in 1985, to play home internationals at Linfield’s Windsor Park, which gives the club a major financial advantage over other clubs.

The IFA has worked intensively, with the Amalgamation of Official Northern Ireland Supporters Clubs, to counter sectarian chanting and flags at international matches, a campaign hailed in a 2005 evaluation by the Belfast-based Institute for Conflict Research as “remarkably effective in transforming the atmosphere at international games”.

With funding from the EU’s Programme for Peace & Reconciliation in Northern Ireland and from Uefa the IFA has extended this community relations effort into clubs which for decades were strongholds of segregation. The IFA conducts “community audits”, advising clubs, many of which are in financial difficulties with dwindling crowds, on widening their appeal and accessing public grants for partnership initiatives.

At the cutting edge of this community relations work has been the disinterment of the extraordinary story of Belfast Celtic, the predominantly Catholic club and former great rivals to Linfield. Celtic folded in 1949 after a sectarian riot at Windsor Park in which a section of Linfield fans invaded the pitch and attacked Celtic’s players. Jimmy Jones, a goalscoring inside-forward who was attracting interest from English clubs including Matt Busby’s Manchester United, was chased, thrown to the ground and violently assaulted, breaking a leg.

Padraig Coyle, a Belfast writer and broadcaster, records in his excellent history of Celtic, Paradise Lost and Found, how the club complained that the police stood by, arresting nobody, and the IFA was wholly inadequate in its response. The Celtic directors, without ceremony or much public statement, gradually sold all the players, then withdrew from football forever.

The Belfast Celtic Society has established a museum, to keep the club’s memory alive, at the Park Centre, a shopping mall built on the site of Celtic Park after it was demolished in 1985. There Jimmy Overend, a Celtic fan back then and now 86, says he can “still smell the match whenever I come here, the tobacco and oranges”.

Of the demise of the club, which had lit up the lives of politically oppressed, impoverished Catholics such as himself, a general labourer, Overend laments: “It was like a black cloud coming down, as if there was nothing to live for or look forward to on a Saturday. It’s a grief which never went away.”

Northern Irish football, some argue, never recovered. Crusaders took Celtic’s place in the league but many fans used to leave Belfast on weekend cattle ships to watch Glasgow Celtic or Rangers, voyages which saw hand-to-hand fighting in the years of the Troubles.

Coyle wrote a play about Belfast Celtic, Lish and Gerry, which was performed to acclaim at Windsor Park last year, supported by the IFA and Linfield.

Coyle says he found the history unexpectedly subtle; the Lish character is Elisha Scott, a Celtic goalkeeper who moved to Liverpool where he became a legend, then returned and was Celtic’s driven manager when the club folded. He was Protestant, while the Gerry character, Gerry Morgan, Linfield’s trainer, was Catholic. The two embody the more mixed Belfast community which existed before the Troubles began in the late 1960s, and Coyle says Celtic’s directors were themselves not beyond reproach.

“The violence against the Celtic players was appalling,” Coyle says, “but it was reprehensible that the club folded with no real explanation given to supporters, who were left with a void.”

Last week the IFA supported a performance of the play in the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont, in front of an audience of politicians whose parties still largely divide along sectarian lines. A community organisation, Healing Through Remembering, helped facilitate discussions afterwards about the issues and emotions provoked.

Chris Lyttle, of the cross-community Alliance party, one of three assembly members supporting the Stormont performance, described the event as “remarkably powerful” for excavating a buried story from Belfast’s past. Lyttle believes such remembrance of Northern Ireland’s troubled, but also nuanced, history should be much more widespread in the province.

“Although a line has been drawn under the violence here, there is a culture of not talking about the past, not having a truth recovery process as they did in South Africa,” he says, speaking in his east Belfast constituency office. “That means stories are told in black and white in separate communities, tensions can remain in place and we are managing differences rather than bringing communities together. With this the IFA is giving a lead which many politicians struggle to provide themselves, to say we can understand the past and move towards a shared, more constructive society.”

Boyd says opening the Belfast Celtic sore is “probably the riskiest thing we have done”, adding: “It is like the old adage: if you do not understand your history, you could be condemned to relive it. Part of the Belfast Celtic tragedy is that we at the IFA let the club and its supporters down. We want people to understand that we have changed, we do not intend to let any section of the community down again. We are determined that in this small part of the world, football should bring people together and be a force for good.”

The Original Corteo

Does the below prove that the modern Corteo fan tradition was really first begun by Belfast Celtic? Possibly, or at least a precursor.

Took 100 years or so for it to return it restart again at Celtic.

An Irish Invasion – Daily Record & Mail – Thursday, January 1st, 1914 – The Original Corteo?

https://photobhoy.wordpress.com/2018/10/27/an-irish-invasion-daily-record-mail-thursday-january-1st-1914-the-original-corteo/…