THE FOUNDATIONS OF CELTIC: CHARITY, RELIGION, POLITICS OR PROFIT?

by The ShamrockPosted on 09/12/2024

THE FOUNDATIONS OF CELTIC: CHARITY, RELIGION, POLITICS OR PROFIT?

Matthew Marr

(@hailhailhistory/@hailhailhistory.bsky.social)

If Disney made a film about Celtic’s establishment, the storyline can be easily imagined.

It would likely open with a scene in Ireland showing the ravages of famine, and people being forced to seek new lives elsewhere. The movie would then depict one of the migrants, a young Irishman, coming to Glasgow and working as a teacher. He would struggle to deal with the grinding poverty faced by his pupils, and take steps to feed them. Eventually, a football club would be formed to raise funds for this cause, and the team would become a beacon of hope for the entire community.

There is of course a strong element of truth to this, although inevitably the full story is more complex. Celtic’s formation certainly did owe much to a desire to tackle poverty, but other factors loomed large. Religious influences were obvious, with a need to promote and protect the Catholic faith of those who came to call the east end their home. And political causes were evident, as some came to see Celtic as a means of promoting Irish identity and nationalism. In later times, there were even cynical suggestions that personal enrichment had been an influence too.

In the modern era, these arguments continue to play out. Many seek to understand the actual nature of why Celtic first came into being, particularly connected to modern day controversies. For instance, fans often argue about the extent to which political causes and identity should be connected to Celtic, whether in terms of Irish or global events. This article will examine each of the possible causes, and reach a conclusion about the true reason for the creation of Celtic Football Club.

Background

Celtic’s story does not begin in Scotland. Instead, you have to look elsewhere. Ireland is an obvious location, but before this, there are connections to France, and even across the Atlantic.

‘Phytophthora infestans’ is not a phrase many will be familiar with, but without this, there would be no Celtic. This was the scientific name for the potato infection that eventually caused a famine across much of Europe. This pathogen likely developed in Mexico (although some accounts suggest the Andes region) and in the mid-1800s made its way over the Atlantic. This soon wiped out the potato crop in various countries, including France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Scotland and, of course, Ireland.

Given Irish reliance on potatoes, the effects of famine – known in Ireland as ‘An Gorta Mor’ (the Great Hunger) – were especially devastating. At least one million people died from starvation or illnesses stemming from this, and another million were forced to flee their homeland. This meant that Ireland’s population, which had stood at 8.5 million in the early-1840s, was down to only 4.4 million by 1901.

In Scotland, Erin’s exiles made their homes in places across the country, particularly the west coast areas of Glasgow, Ayrshire and Lanarkshire, but also east coast cities such as Dundee and Edinburgh. These immigrants soon faced the same problems of poverty as many native Scots were forced to endure. This included housing overcrowding (with around one-third of Scots living in one-roomed homes), unemployment, low pay and little or no government support to overcome this.

In Glasgow’s east end, conditions were especially crippling. Different groups tried to tackle these problems, providing various types of help and support, including education for local young people. One such organisation was the Marist Brothers. This Catholic organisation had been founded in France in 1817, and spread to provide education in countries around Europe and then the world.

The impact of events in Mexico, Ireland and France would soon coalesce in Glasgow in the figure of Andrew Kerins, a young Irishman. Born in Sligo in 1840, Kerins had grown up during the famine and when aged 15 came to Glasgow to build a new life. Little is known of his early Glasgow years, but it is believed he worked on the railways, before later joining the Marist Brothers. In Glasgow, Walfrid initially worked in St Mungo’s School, before being sent to St Mary’s School and finally, Sacred Heart School.

As head teacher at Sacred Heart, Walfrid recognised that hunger was a major barrier to children’s chances of learning. This was based on concentrating in class, and attending school at all. As such, he introduced the Poor Children’s Dinner Table, a scheme that allowed children to buy a meal each day for one penny (although payment was not insisted upon). This proved to be successful but expensive, and so steps had to be taken to raise funds for this.

Initially, the scheme was supported by a local branch of the Catholic charity, St Vincent de Paul. However, other steps were taken too. One of these was using football teams to hold games, with the proceeds going to the Penny Dinners scheme. Bridgeton team Clyde often did this, playing at their home ground of Barrowfield. Clubs came from further afield too, including Edinburgh Hibernian and Dundee Harp. Walfrid was also responsible for organising a team called Eastern Rovers who were connected to Sacred Heart.

Hibernian were especially popular with local fans, a symbol of Irish success and achievement in Scotland. This was especially the case in February 1887 when the Edinburgh men won the Scottish Cup, then Scotland’s most important football contest. After beating Dumbarton 2-1 to claim the trophy, the Hibs men went to St Mary’s Church in the Calton where a celebration was held. Such was the acclaim given to the cup winners, the question of why Glasgow’s east end did not have their own Irish team soon arose.

Later that year, this situation would change. On 6 November 1887, a group of people went to mass at St Mary’s Church. Afterwards, they decanted to a nearby hall – located at 67 East Rose Street – where they discussed plans for a new football team. This club was to be named Celtic. Up to now, the facts are all fairly simple and without dispute. But why exactly did this happen? What were the specific motivations and aims of the group that met in East Rose Street?

Brother Walfrid

Poverty/charity

In Celtic lore, the story of the club being formed to feed the poor and the hungry is well-known, so that would seem to be an obvious first point of discussion. Just what is the evidence that charity and tackling poverty were indeed the club’s principal motives?

It is not difficult to find a range of sources to support this view. Perhaps the most obvious starting point would be the earliest official statement from Celtic. In January 1888, a circular was issued which told of the new club’s formation, and sought help from different people to make it a success. The opening paragraph gives a clear as statement as is surely possible about why Celtic were established:

“The main objective of the club is to supply the East End conferences of the St. Vincent de Paul Society with funds for the maintenance of the ‘Dinner Tables’ of our needy children in the Missions of St Mary’s, Sacred Heart, and St. Michael’s. Many cases of sheer poverty are left unaided through lack of means. It is therefore with this principle object that we have set afloat the ‘Celtic’, and we invite you as one of our ever-ready friends to assist in putting our new park in proper working order for the coming football season.”

There is little more to add to this. The men that set up Celtic made it clear that their main goal was to feed poor children in Glasgow’s east end. In fact, this and other charities were at the heart of the club’s thinking, evidenced by a report in Celtic’s first ever annual general meeting, held in June 1889. This gave a breakdown of various types of expenditure associated with the club. Celtic’s turnover since its foundation had been around £3800; just over £420 of this went to charity, including £51 to different branches of the Poor Children’s Dinner Table, and other Catholic charities too, such as the Saint Vincent de Paul Society, and Little Sisters of the Poor.

In fact, there is even more evidence of the charitable mission which helped create Celtic. In the club’s opening years, many other good causes benefitted from Celtic’s contributions, locally and further afield. For instance, after the Templeton Factory Disaster of 1889 – when a wall collapse killed 29 women weavers – it was Celtic who were one of the first to donate to the fund set up to assist the survivors. The Bhoys also became well-known visitors across Britain, playing games in various towns and cities that aimed to support a range of different causes.

This charitable commitment was acknowledged by those outwith the club too. In their first season, Celtic reached three finals, losing in the Scottish Cup and Glasgow Exhibition Cup, and winning the Bhoys’ first trophy, the Glasgow North Eastern Cup. The Scottish Referee publication wrote that “If it were only for the good they have done to poor suffering humanity the Celts deserved better luck. They should remember that small beginnings make big endings,” suggesting that Celtic’s donations made them a club worth celebrating and that deserved success. An 1892 edition of the Scottish Football Annual also said that “The primal object of [Celtic’s] formation was charity.”

However, there is also evidence that this support for good causes later began to wane, which some people have interpreted as evidence that charity was not truly the club’s founding goal. There were multiple complaints that Celtic’s committee was not giving enough money to charity and was instead focusing on paying players (technically illegal until 1893) and building the ground. This was even part of the reason that a rival Irish team was established – Glasgow Hibernian – although this new side died a quick death.

Most symbolically, this was evident in 1893. Brother Walfrid – renowned as the club’s founder – had departed Glasgow in 1892, going to work in London. In the season he left, Celtic failed to make any donation to the Poor Children’s Dinner Table, the very cause that Celtic were supposed to help. This was particularly galling given that Walfrid himself later wrote about the importance of this funding, saying “The expenses for some time were met by subscriptions and collections, sermons, etc, til the Celtic FC was started.”

To a point, this was inevitable. The costs of running an increasingly professional team (officially so from 1893) put huge pressure on club finances. In particular, the building of a new Celtic Park – at a cost of more than £3000, then an enormous sum – meant that Celtic’s debts necessitated a change in how it spent its money. The Catholic newspaper Glasgow Observer was especially scathing of this shift from the original commitments. They later wrote a pleading editorial demanding that “Can we not get a club that will carry out the original idea of Brother Walfrid?” The inference was clear; Celtic may have once had charitable goals but these were being eroded by the men now running the club.

Celtic stepped even further away from charity when they became a private company. For years, there had been proposals that Celtic should cease to be a member-owned organisation and instead become a limited company. Part of the reasons for this were understandable – club owners were themselves liable for debts – but others saw this as a power and finance grab. Once more the Glasgow Observer criticised this, saying such a move would “annihilate charity – the original article in the club’s creed.”

Finally, in 1897, Celtic members voted to become a private company, and 5000 shares were issued in the club. In the future, this required that a 5% dividend be paid to shareholders before charity donations were made. Although contributions would continue to be given to various causes, the need to first pay money to shareholders clearly shifted the club away from any early mission it once had.

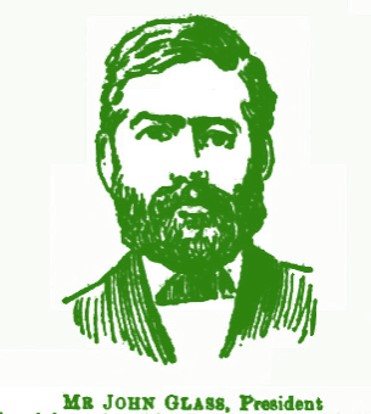

It is undeniable that the principal spark which ignited Celtic into existence came from a drive to help the less fortunate. In the words of club President John Glass at one annual meeting: “But for charity, the Celtic club would never have been organised.” However it is equally evident that this mission did not remain the club’s sole purpose as the years advanced.

Religion

Charity and tackling poverty were clearly an intrinsic part of Celtic’s founding goals. But there are other factors to be considered too, not least the influence of religion.

If the club’s opening circular (issued in January 1888) can be used as evidence of Celtic’s early commitment to good causes, it can also be used to emphasise the religious influence. This features five direct references to the word “Catholic”, highlighting the need to represent Catholics in the west of Scotland and give young Catholic men a sporting activity in which to participate. In fact, there are multiple references to “Catholic” and religion before any link is made with poverty.

This circular also identified the men who were the driving force behind the club’s establishment. Its opening line has an overt religious link, stating that the patrons were “His Grace the Archbishop of Glasgow and the Clergy of St. Mary’s, Sacred Heart and St. Michael’s Missions, and the principal Catholic laymen of the East End.” It also makes it clear that the “needy children” to be fed are those from “the Missions of St Mary’s, Sacred Heart, and St. Michael’s.”

As a result of this circular – which aimed not simply to announce Celtic’s arrival but also solicit donations to fund the club’s establishment – numerous people committed money. These people were almost exclusively Catholic and five of them were notable members of the Catholic clergy in Glasgow. And of course it was well-known that priests were to be found amongst the Celtic Park crowds.

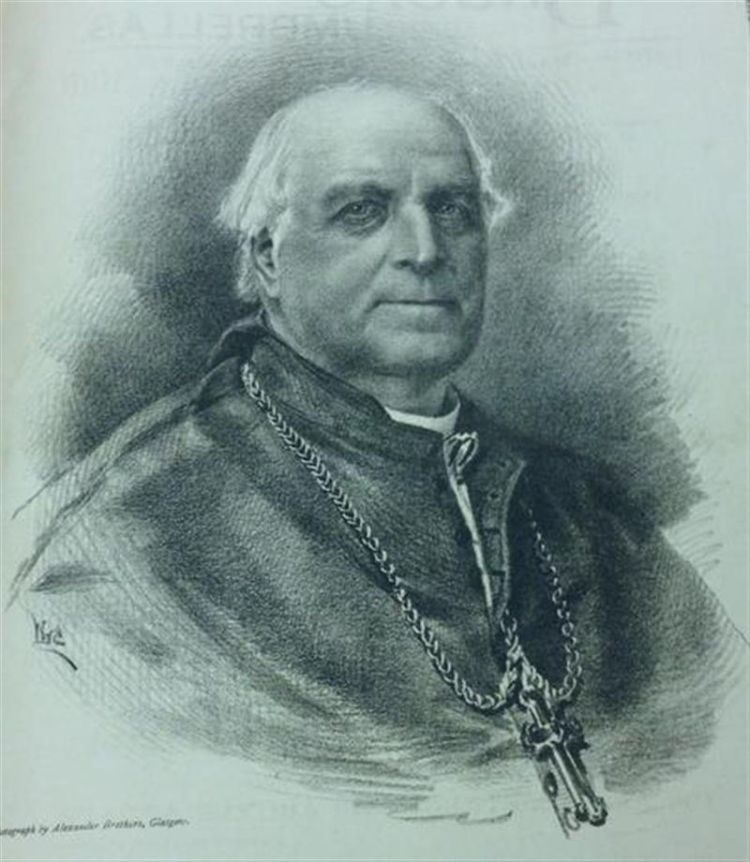

These men would no doubt have been driven by a desire to tackle poverty, but spiritual concerns would have influenced them too. After all, Archbishop Charles Eyre – Glasgow’s most senior Catholic and the first Catholic Archbishop in Glasgow since the Reformation – was from an English Catholic background. He would have little interest in Celtic’s Irish identity but would certainly have worried about the religious challenges facing Catholics in Glasgow.

The poverty endured by the migrants created an issue that concerned the Catholic hierarchy; Protestant soup kitchens. These institutions offered sustenance to those in need, but it could be at the expense of renouncing their Catholic faith. Such an action would have concerned senior Catholics in Glasgow, worried about the loss of their flock. This meant providing a Catholic alternative to these Protestant charities, shown through initiatives such as the Penny Dinners scheme.

Indeed, this involvement with other Catholic organisations was one that united many of Celtic’s founders. Archbishop Eyre and figures such as Dr John Conway (the first man to ever kick a ball at the original Celtic Park) were involved in the Whitevale Children’s Refuge, not far from Celtic Park. Other Celtic figures were part of Catholic community groups, such as the Catholic Literary Society. In addition, many of the tickets for Celtic games were sold and promoted through the Catholic charity St Vincent de Paul, which had been the original source of funding for the Poor Children’s Dinner Table.

Celtic’s reputation as a Catholic club was something strongly recognised in wider society. Different newspapers sometimes referenced the Bhoys as being the “Catholic club” in match reports. This could be done with a critical edge – the Scottish Referee publication once bemoaned Celtic’s commitment to Catholic charities, rather than general good causes – but often it was just used as an alternate title for the Celts, in the same way as journalists would write “the green team” or “the Parkhead men.”

Even off the field, this club and religion connection was noted. One notable part of Glasgow’s social calendar was the Catholic Charity Ball. Many key Celtic organisers – such as William McKillop – helped host this event, and other club founders attended, including Joseph Shaughnessy and John H McLaughlin. At another time, the annual ball held by Celtic FC was described by the Glasgow Examiner as being “the only Catholic dance of the season.”

It may be that this recognition about Celtic’s Catholic links came from the club’s charity priorities. When Celtic first entered the Glasgow Charity Cup, they did so on the understanding that proceeds from this competition would now be given to Catholic charities, which had not been the case beforehand. In addition, when Celtic went across Britain playing charity friendlies, many of these tended to be for Catholic causes, including a church in Stoke and school in Manchester. Parishes in other parts of Glasgow recognised this and even considered setting up their own Celtic-type club.

Nevertheless, despite these strong links, Celtic were not founded as an exclusively Catholic club. The existence of Glasgow Hibernian – referred to the in the previous section – provides evidence for this. Some of the people involved with Glasgow Hibs wanted Celtic to mirror Edinburgh Hibs’ initial policy of playing only Catholics, but this was never a plan pursued by Celtic, with examples of Protestant players turning out in Celtic’s green-and-white early in the club’s history.

This was also something acknowledged by contemporary newspapers. An 1892 article in the Scottish Referee summarised Celtic’s identity as: “The Celtic players are Scotsmen of Irish extraction, and although a preference is shown for members of the Roman Catholic Church, several Protestants have been members of the team.” And one 1889 report in the Scottish Sport said “The difference between the Celtic and Hibernians is that the latter was both a religious and a political organisation. The majority of the members of the Celtic, it is true, belong to one religion but adherents of other religions are not debarred from joining the club and playing in the team.”

Archbishop Charles Eyre, Celtic FC’s first patron

Politics/Irish identity

There is a very clear connection between Celtic’s foundation and the causes of charity and religion. However, other people have suggested that politics also played a role, not least Irish political causes of the era. This is a view particularly relevant nowadays given the political campaigns of many Celtic fans, including groups such as the Green Brigade.

Part of the problem with this issue is an understanding of what would have been meant by politics in the late-1800s. It could be argued that the establishment of a football club to help tackle poverty was a political act, designed to challenge the failure of governments to act. However, some believers in Marxism may argue that in fact charity is essentially an endorsement of capitalism, in that it seeks to limit the damage of that ideology, not end that system.

On the other hand, others contend that Celtic’s formation was more about Irish politics. Again, this can be read in different ways. It could be seen as an organisation that simply promotes Irish identity in Scotland, as well as the diaspora’s developing position in their new home. Or it could be connected to Irish constitutional debates of the time, not least that of Home Rule. That would also open up a further avenue of contention; what change was desired? Officially, Home Rule meant Ireland having its own government whilst remaining part of the British Empire, a view many Celtic figures backed. However others favoured a more radical approach of genuine Irish independence, although this did not become the dominant demand until after World War One.

Almost to a man, every notable early Celt (both founders and players) was Irish-born or second- or third-generation Irishmen. Newspapers recognised this and repeatedly described Celtic as “the Irish club” or “the Irishmen” in match reports. This was not simply the case in Scotland. It can be argued that in the absence of a dominant and famous football team in Ireland meant that Celtic came to be seen as the main symbol of Irish football. When Celtic travelled across England, local newspapers were amazed at the huge crowds drawn to watch them, a phenomenon which was generally attributed to Celtic’s Irish heritage and the way this encouraged diaspora communities across England to turn out to see ‘their’ team.

Celtic’s players certainly saw themselves in such a light. An 1893 article in the Scottish Sport conducted interviews with the Celtic team during an after-match reception in a Glasgow city centre restaurant. One of the questions asked if “the Celtic football team [was] comprised entirely of Irishmen?” To which the players answered “Yes. All Irishmen.” Even if there was any humour in this response – the same article acknowledges that all were actually born in Scotland to Irish parents – it does suggest an identity issue which would presumably have been felt by many fans too.

This association between Celtic’s fans and Irish political causes can be seen in newspaper articles. One obvious one stems from Celtic’s first ever cup success, the Glasgow North Eastern Cup, which was won in May 1889. The Scottish Referee wrote of this achievement that “Had a present of Home Rule been made to the ‘distressful country across the way’ on Saturday afternoon, Irish Bridgeton could not have been more jubilant on Saturday night.” Leaving aside the amusing connection between Irishness and Bridgeton – given twenty-first century reputations – it also shows Home Rule was an issue strongly connected with all Irish people, which would include prominent Celts.

Many of Celtic’s founders were heavily involved not simply in football or religious activities, but Irish nationalist causes too. John Glass was one key example. Glass was a Glasgow builder who hailed from a Donegal family. He was a major figure in Celtic’s formation – arguably just as important to the club’s rise as Brother Walfrid – and also at the heart of Irish political campaigns. This included being the Secretary of a branch of the Irish National League, whose events he regularly attended. Another example of was William McKillop, who was born in Scotland to Irish parents and later became an Irish nationalist MP.

A further illustration relates to John Conway. As well as many Catholic groups, he was also involved in Irish organisations. After Hibernian won the 1887 Scottish Cup and came to St Mary’s Church for a celebration, Conway gave a speech where he noted the positive role that Hibs were playing in boosting Irish identity. He said that “The effect of [Hibernian’s victory] on our own happiness will not be the only good result derived for each advance will vastly increase the weight of our influence and so enable us to render more efficient assistance towards obtaining for our country that which the united political sagacity of our trusted leaders has indicated as the first essential to her happiness – namely Home Government.”

Various other club actions connected them to politics, including an association with the Irish National Foresters. This charitable organisation was a strong supporter of Irish nationalism. Founding Fathers such as John H McLaughlin spoke at Foresters events. On different occasions, groups of Foresters attended Celtic games, sometimes being given free tickets by the club. Other Celts – such as club officials and players like captain James Kelly – attended notable events focused on the Irish Home Rule campaign, including the 1896 ‘Irish Race Convention’ in Dublin. This mass meeting aimed to unite various factions around the world to campaign for constitutional change in Ireland.

The Bhoys also supported those actively involved in political campaigns. This includes donating money to the legal defence fund for Father James McFadden, a Donegal priest imprisoned for his campaigns against unfair rent. In addition, in 1895, the club held a fundraising event to support the Irish National League, a pro-Ireland political party founded by Charles Stewart Parnell. Taking place in Old Barracks Carnival on the Gallowgate, a “Grand demonstration night … was held under the auspices of Celtic Football Club.” It included various attractions, including a monkey house, water chute, high diving, balloon ascents and parachutists.

An added example of Celtic’s financial support for Irish political causes comes in the final game played at the original Celtic Park. In an irony which was noted at the time, Celtic had been formed partly because of the greed of landlords forcing out the Irish from their homes. Then in 1892, Celtic were forced to do the same as there was an attempt to increase their rent ninefold, leading to them moving to second (and current) Celtic Park.

Celtic’s closing game at their first ground (which actually continued to be used for other football games for years after this) came versus Clyde in July 1892. Apart from it being the last match, it was a game which was otherwise lacking interest and ended 1-1. The final man to score for Celtic on this ground was Johnny Madden. All the proceeds from this went to the ‘Evictions Fund’ which aimed to support Irish families that had been forced from their homes.

The most famous political link between Celtic and Ireland comes in the form of Michael Davitt. He was one of the foremost Irish politicians of the age, a former Fenian prisoner who became a well-known campaigner on land rights. This was not simply in Ireland but also in Scotland – particularly in the Highlands – and around the world too. Davitt was not even the first Fenian attached to Celtic; Pat Welsh had also been an activist and later had a major role in the club’s establishment, including bringing Willie and Tom Maley to the club.

At the club’s first annual meeting – held in June 1889 – Michael Davitt was chosen to be a patron of Celtic. This was a hugely significant action, which firmly tied Celtic to political causes of the time. Davitt’s most high-profile association with the club came at the second Celtic Park. In March 1892, he laid a sod of turf at the ground to mark its construction, ahead of it being properly opened later that year. Sadly, it was dug up that same night and stolen! During this visit, he attended a dinner as Celtic’s representative and was presented with the Glasgow Cup, following the Bhoys’ recent victory in the competition.

The association of Celtic and Davitt gave the club a very clear political dimension, and the turf-laying event lent further emphasis too. The politician’s presence assured this, as was the decision to use imported Donegal turf for the sod laying ceremony. Davitt was also not the only Irish politician in attendance, so too was Timothy Daniel Sullivan, then a Dublin MP. Sullivan is best remembered for writing the song ‘God Save Ireland’, and this was sung at the end of the ceremony.

This was not the only occasion that Davitt attended Celtic Park, or that the Bhoys expressed a political preference. In August 1894, he came back to Glasgow to attend a friendly game between Celtic and Queen’s Park. Davitt’s five-year-old son – wearing a Celtic badge and a cap bearing the word ‘Celtic’ – kicked off the match, which ended in a 1-1 draw. Afterwards, Celtic presented Davitt with a cheque for £60 to be donated to the Irish Parliamentary Fund. In fact, various Irish MPs would often attend Celtic fixtures as guests of the club, including notable figures such as John Redmond and John Dillon.

Davitt was clearly interested in sport. He was once quoted as saying that he did not watch football more for fear that “if I were to be too much exposed to it, I would likely to become so infatuated altogether, and forget about politics.” However it is also important to not overestimate Davitt’s footballing links. For instance, a recent book by Cormac Moore looking at the history of Irish football fails to make any direct reference to him.

Michael Davitt was also a patron of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). This is perhaps a much more obvious link, given the modern day perceptions of this game as being nationalist. For years, football (soccer) was controversial in Ireland. It was sometimes referred to as a “garrison game” associated with the British Army’s presence in Ireland. And until relatively recently, football was not allowed to be played at prominent GAA grounds, such as Croke Park. This might make it seem strange that football and Celtic would become such prominent symbols of Irishness, and also explain why Scotland-formed Celtic came to be the biggest ‘Irish’ team in Britain.

In the modern era, there are different examples of incorrect claims about Davitt and his Celtic connections. Some of these are based on dates, such as confusing the fact that Davitt helped open the second Celtic Park in 1892, not the original one in 1888. More significantly, the Michael Davitt Museum in Mayo claims on their website that it was the Irish political leader who named Celtic. Given that Davitt’s first official involvement with Celtic comes in June 1889 (his AGM appointment as patron) – almost two years after the club was formed in November 1887 – this would appear to be wrong.

The actual origin of Celtic’s name is one of debate. One oft repeated belief is that it was chosen to suggest a link between the Scots and the Irish; this may be the case although no documents exist which specifically support this. There certainly were other footballing Celtics and noted club researcher Brendan Sweeney has suggested the idea may have come from another Marist Brother based in Glasgow, Brother Ezekiel. Whatever the origin, the pronunciation is something which changed. Walfrid wanted the name to be spoken as ‘Keltic’, which did not happen. An 1892 newspaper article said this was also the way that Davitt pronounced the name, although again it certainly was not a title that he gave the club.

Some people even argue that this specific name undermines the idea of Celtic’s formation being designed to promote Irishness and political causes. Irish club names in Scotland tended to have very overt homeland links – such as Erin, Shamrock, Hibernian, Emmett and so on – whereas Celtic was not so explicit. The term ‘Celtic’ of course connects not simply Ireland and Scotland but also other areas including Wales and France.

Furthermore, unlike religion and charity, politics was not immediately referenced in Celtic’s formation. The opening circular of 1888 which repeatedly cites religion and charity makes no mention of politics, or even the words ‘Ireland’ or ‘Irish’. This perhaps suggests that, at least at first, Celtic were not seen as a vehicle to promote these issues or ideas, although this did change reasonably quickly. This lack of direct reference does not automatically mean that such sentiments were not held by Celtic founders, simply that it was not a primary goal of the club when formed.

Another argument against politics being a key part of Celtic’s foundation is the question of the type of politics being promoted. In much the same way as modern day arguments exist, the early Celtic founders were divided on contemporary issues. One example relates to the Boer Wars of the late-1800s and early-1900s, which saw British forces engage in conflict in the south of Africa. Some Celts publicly opposed the hostilities, including figures like John Glass, and also club patron Michael Davitt who resigned as an MP on account of this. However others – such as John H McLaughlin and another of Celtic’s early patrons, Archbishop Eyre – donated money to support the British forces. In fact, when a ‘Patriotic Sports’ event was held in 1900 to raise funds for Britain’s soldiers (and victims of the Indian famine), Celtic Park was chosen as the host venue.

This was the same divide which arose during the First World War (1914-18). Whilst many Irish were split on supporting Britain during this conflict, others backed the British military. Various Celtic players and fans served overseas during this time. Recruitment events took place at Celtic Park, including tannoy announcements encouraging fans to join the army, and various types of financial support to help the war effort came from Celtic.

The idea of Celtic being widely recognised as an Irish nationalist club may also be undermined by events surrounding the purchase of Celtic Park. In 1892, the Bhoys were forced to move from their original home. The new land to which they moved was owned by James Hozier, then a Conservative MP. He later became Lord Newlands, and was also a Grand Master Mason of Scotland. Despite this background, Hozier agreed to sell the land for the second Celtic Park to the club. Whilst money can open many doors, it might be argued that such an avowed unionist would have been less likely to sell the land if Celtic were truly seen as a vehicle for Irish nationalism.

There is little doubt that Celtic and Irish identity came to be strongly linked, and with the growth of Celtic, many saw the opportunities it gave to promote political causes. However, this would appear to be something which happened after Celtic’s formation, rather being than a driving purpose of its initial establishment.

Green Brigade display at Celtic Park honouring Michael Davitt

Business interests

It is discussed less, but there is potentially a more cynical explanation to the formation of Celtic – that of personal enrichment. For all the romantic stories of Celtic’s establishment, within a short period of time there was a clear business focus which would see Celtic become a private company within a decade. In consequence, it has been suggested – sometimes by people who do not wish Celtic well – that the club’s foundation was not as altruistic as it seems.

As noted earlier, Celtic’s initial formation was not an especially newsworthy event. Edinburgh Hibernian were already an established side, and Dundee Harp had a prominent reputation too. In addition, there were multiple examples to be found across Scotland of other local Irish clubs. Celtic would have simply merged into this mosaic of clubs, and it would not have been a shock had they become yet another Irish footballing casualty. Instead, the opposite happened. Celtic’s rise was meteoric; even by late-1888 – just months after their first game – newspapers were describing them as the “already famous Glasgow Celtic.”

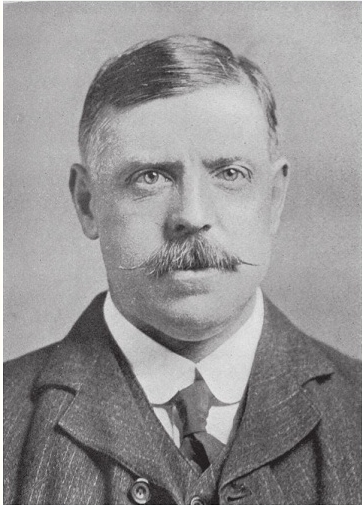

The reason for this was the substantial organisation and financial backing which underpinned the new club. Within one week of Celtic’s 6 November 1887 establishment date, the Bhoys had rented land (near the modern day Celtic Park) that would become their first ground. This was later followed up by an influx of the top Irish diaspora players in Scotland, including men like James Kelly and Neil McCallum, who were crowned as ‘World Champions’ with Renton earlier in 1888.

Celtic’s financial strength – shown in their ability to quickly secure land and top players – has led to some speculation that richer Irish businessmen may have seen the club as a vehicle for purposes other than charity. It could feasibly be the Irish dimension discussed previously, but it could also have been a wish to tap the growing finances that were available as football became established as the country’s top sport and pastime.

Celtic’s ability to attract many of these players, and persuade others from moving south to England’s relative riches, was clear evidence of money available to the club. Until 1893, it was against football rules to pay players, although in reality most clubs secretly did this, including Celtic. There were various routes to achieve this, although Celtic made particular use of pub licences. Thus, James Kelly – a joiner by trade – was able to afford a £650 pub licence. Such an approach often drew criticism for Celtic, not least from people who opined that one reason for the poverty many children faced was the alcoholism of their parents.

Different Celtic figures were the heart of allowing players to legally be paid. People like John H McLaughlin pushed to have a Scottish League, and then followed this with a demand for professionalism. This was formally introduced in May 1893. After this, it naturally led to an increase in the wages paid to players, taken from club finances. Inevitably, this reduced the funds available for charities. Such a move was often criticised in the Catholic press, with complaint letters describing players as living in “lazy idleness,” doing little work and taking money from charitable causes.

The paying of club officials drew opposition too. From the early-1890s, Celtic’s committee agreed to pay different figures involved in the running of the club, something others saw as anathema to the club’s charitable foundations. However, many others – including Brother Walfrid, of all people – backed this move, recognising that it was necessary to secure the growth of the club, including its ability to make money which could be given to good causes.

The issue of charitable donations can be used as evidence for and against the view that Celtic were just a vehicle to make money. Certainly donations did decline over time, particularly the early failure to give funds to the Penny Dinners scheme. However, Celtic still made significant contributions to a range of good causes. In the first year alone, more than 10% of club turnover (not profits) went to charity, a significant sum.

Even more significant as evidence of business motives in Celtic’s formation is the fact that there were repeated steps to change from a member-owned club to a private company. This caused various fights between Celtic members. Giving Celtic Limited Liability status would mean shares were issued by the club, and this finally happened in 1897. 5000 shares – valued at £1 each – were sold, giving a small number of people a dominant control of Celtic, one that lingered a century later into the 1990s.

It is clearly possible to read these facts and assume a cynical motive behind these actions. In fact, Limited Liability status was one being gradually pursued by most British clubs. The reasons for this were partly about personal protection for committee members, who otherwise faced being personally liable for debts incurred through the football club. This was especially daunting as clubs invested in their grounds, often at great cost. Celtic’s committee especially may have seen the example of Glasgow Hibernian – whose collapse resulted in court cases for their funders – and wanted to protect their own interests.

As well as this, a look at many of the key men who drove Celtic’s formation further undermines the notion that their motive was profit. The most obvious of these is Brother Walfrid, whose life was devoted to the Church, and who took a ‘vow of poverty’ as part of joining the Marist Brotherhood. This same sentiment can be expressed for people such as Archbishop Charles Eyre. In addition, there are accounts of Michael Davitt being given expenses to organise events and then handing back unused funds, again proving that personal enrichment was not a driver of Celtic’s backers.

There is little doubt that Celtic’s focus eventually moved away from charity and began to have a clear business focus. This was inevitable if the club was to grow. The rise of professionalism (in England as well as Scotland) created competition for players and failure by Celtic to adapt to these conditions could have seen the club’s demise, in the same way as many other Irish teams experienced. The Celtic committee (and later Board) instead responded to footballing demands – and perhaps also a desire for personal control – which led to changes in how the club was run. However, there is no evidence that the wish to make money was the purpose for which the club was originally formed.

James Kelly: Celtic player, captain, Chairman

Conclusion

The issue of what drove Celtic from the very start has always been a slightly ambiguous one. For one thing, the answer partly depends on the time period to which this refers. Does it mean simply the initial formation on 6 November 1887? Or is it more relevant to look at the early years of the club’s existence and the various influences which existed?

In understanding why Celtic were originally established (based on the 6 November 1887 date), there is little need to look further than the club’s opening circular. This spells out in very simple terms what drove such matters; it was a commitment to tackling poverty in the east end area, allied to a need to protect and promote the Catholic faith. The fact that it makes numerous references to both those issues, without making any mention of Ireland, is beyond dispute.

However, it is also the case that after formation, Celtic’s goals began to alter. For one thing, there was a clear shift away from charity, especially once Celtic became a private company. There is also an obvious rise in political links and associations, not least when Irish nationalist politician Michael Davitt was invited to become a club patron. However, the fact he was the second patron (the first being Archbishop Charles Eyre) possibly illustrates the order of the club’s earliest priorities. Furthermore, whereas Celtic’s founders all hailed from a Catholic background, it would be wrong to assume that they were united on every political topic, with multiple disputes evident as the club grew older.

It is often the case that people who strongly argue for a particular issue as being Celtic’s reason for existence are simply mirroring their own views. Instead, when it comes to the factors which led to Celtic’s establishment and rise to prominence, the most accurate opinion is that there is no ‘exclusive’ answer. Charity needs were to the forefront, but not an ‘exclusive’ factor influencing affairs. The need to defend the Catholic faith was also of significance, but again, not ‘exclusively’. Politics and Irish identity were not immediate priorities but soon came to the fore, although once more, not as an ‘exclusive’ concern. Instead, all three of these issues – likely in that order of importance – were what drove Celtic’s earliest days.

It’s also worth saying that the question could even be posed: “does it actually matter?” In the modern era, Celtic’s own Social Charter says that it is “An inclusive organisation being open to all regardless of age, sex, race, religion or disability.” This means that there is no requirement to be Irish or Catholic – or any other background – to follow the club. This is certainly true. Equally, if Celtic is to be more than simply a football team or money-making venture, it helps to have some ideals to which it is anchored, whether it is the fans or club itself which most embody these values.

As further evidence of the confusion surrounding this matter, there is a famous quote that is associated with Celtic’s inception, which begins: “A football club will be formed…” In fact, there’s no evidence for this statement ever being uttered or written down, but it does cut to the heart of what matters most on this topic. Instead, let’s look at an actual excerpt from the Bhoys’ first circular: “Celtic Football and Athletic Club … was formed in November 1887.” Ultimately, Celtic came into being, and that’s the most important thing, regardless of what anyone – including Mickey Mouse – has to say about it.

———-

Matthew Marr is a Celtic historian who contributes to a range of publications and online sites including The Celtic Underground, The Celtic Blog and The Shamrock.

Matthew’s first book is The Bold Bhoys: “Glory to their name” The Story of Celtic’s first Title. More information here: https://x.com/celtsfirsttitle

Matthew also organises free Celtic Walking Tours throughout Glasgow documenting Celtic history. More information can be found at: https://celticwalkingtours.wordpress.com/