All below articles are by 1) Celtic historian & fan Liam Kelly (@cfcliamk96) and 2) added a few by others with source links.

Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 1)

By Liam Kelly

Celtic have a connected yet complicated history with Hibernian. Some fans have a soft spot for one another, but these are few in number. The more common feeling is one of indifference or dislike between the clubs these days. Certainly, both sets of supporters will be hoping for nothing less than three points next Monday evening!

The first point of contention surrounds Celtic’s founding. The accusation has often been that Celtic simply copied Hibernian, having been encouraged to do so after the Hibee’s Scottish Cup triumph in early 1887. A jubilant reception was held in St Mary’s Church Hall in the Calton that day, and various quotes are reported to have been said by John McFadden (Hibs Secretary) and Dr John Conway (one of Celtic’s founding fathers). These quotes were to the effect of McFadden encouraging those in attendance to “go and do likewise” (establish a football club for the Irish community in Glasgow), with Conway speaking very keenly of the idea “not only for social but for political matters as well, so that the goal of every Irishman’s ambition – legislative independence of his country – will soon be attained.”

The success of Hibernian, and that occasion at St Mary’s, certainly played a major role in the emergence of Celtic Football Club later that year. The gauntlet had been laid down by McFadden, however, other factors cannot be forgotten.

Brother Walfrid and Brother Dorotheus had already been hosting charitable football matches to support the Penny Dinner Scheme, which they operated within The Poor Children’s Dinner and Breakfast Tables (at St Mary’s and Sacred Heart schools). A mark of the problematic overgrowth of the scheme was that Sacred Heart provided 48,500 dinners and 1,150 breakfasts in its debut year. Added to this huge level of service was the fact that the school capacity had quadrupled and was to educate over 1,200 pupils for the school year of 1886. Similarly, St Mary’s started the first six months of 1886 by serving 26,421 meals to students, 17,707 of which were free of charge. Rather than make the suggested donation of a penny compulsory, the decision was made to reach out to other aspects of social assistance.

The Marist Brothers soon branched back into football having seen the enjoyment that not only their pupils, but the working class people of Britain had got from playing the sport. The pair set up youth football leagues for former and current pupils of each school, whilst Walfrid also founded a few teams of his own, which were associated with his other community organisations, including one outfit born from the literary society that he had developed for local Irish linguists.

Walfrid had already invited Edinburgh Hibernians to travel to the east end of Glasgow on 26 September 1885, where a reserve team fulfilled a charity game against a junior club named Glasgow Hibernian. After that match, the Edinburgh side were fed and entertained by the St Vincent De Paul Society at St Mary’s Church Hall. The initial match had been disappointing. On the park, Edinburgh Hibernians won 6-0 and off it a small amount of money had been raised.

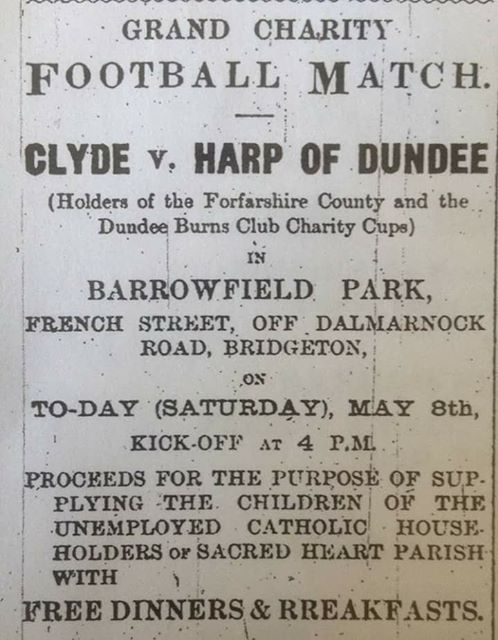

Undeterred, it was on a mid-May afternoon in 1886, that Brother Walfrid managed to get Harp of Dundee, one of approximately 40 Irish teams in Scotland at the time, to accept Clyde’s invitation of a charity match at their former home pitch – Barrowfield Park. Harp of Dundee stole the win with a late goal to make the score line 2-1 in their favour. This time the match’s fundraising success was resounding. All proceeds from the event went towards The Poor Children’s Dinner and Breakfast Tables. Therefore, it was fitting that both teams were invited to Sacred Heart School for a post match meal.

The Marists organised a further match on 18 September 1886, with Walfrid’s Eastern Rovers visiting Glengarry Park to face a St Peter’s Parish team that he had also become involved with, named Columba. Funds continued to roll in thanks to a crowd of over 1,000 on that occasion.

Interestingly, John Glass (who would later become the founding father who Willie Maley claimed Celtic owe their existence) had formed a club named Eastern Hibernians, who also locked horns with Columba in this period, thus bringing Walfrid, Dorotheus and Glass together within the footballing arena.

Another team of note at this time was Western Hibernians, who played in exhibition matches and were also instituted to The Poor Children’s Dinner and Breakfast Tables. The Western Hibernians donned white shirts, black shorts and green and black hooped socks. In an exhibition match in February 1888, they fielded no fewer than seven of the 11 players who would play in Celtic’s first match three months later!

These events outline some of the key happenings as a precursor to the founding of Celtic Football Club. One of the final pieces in the jigsaw, serving as confirmation to the idea, happened through a stroke of good fortune…

A charity exhibition match was organised at Glengarry Park on 26 May 1887. This time it was evident that Brother Walfrid and an embryonic committee of men, who would go on to found Celtic, were behind the match. The organisation was much better than previous charity games in Bridgeton. A trophy had been offered up to the winner, which enabled the clash to be labelled ‘The East End Catholic Charity Cup’. A major coup was also secured, when the competing teams were announced as Edinburgh Hibernians and Renton. The magnitude of this contest should not be understated, for Hibernian were Scottish Cup holders; whilst Renton held the Glasgow Merchant’s Charity Cup (the cup committee invited some teams located on the periphery of Glasgow to compete) and Dunbartonshire Cup trophies.

The improved planning paid off when 12,000 fans paid entry to the fixture, a larger crowd than that which attended the Scottish Cup Final three months earlier. The score finished 1-1, meaning a replay and another pay day beckoned. The replay was penciled in for the beginning of the new season, on 6 August 1887. A reduced, yet respectable crowd of 4,000 arrived excited at what lay in store. They weren’t disappointed as Neil McCallum, who would go on to score Celtic’s first ever goal, struck the net five times in a 6-0 win for Renton.

Following the match, the Renton and Hibernian parties were cordially invited to the Sacred Heart Boys Club for a post-match reception. There, it was revealed that the combined crowds of 16,000 over the course of the two games, had raised some £120 (equivalent of £15,000 in today’s money) which was primarily donated to The Poor Children’s Dinner and Breakfast Tables, but was also dispersed among charities in Edinburgh and West Dunbartonshire.

The Sacred Heart parish had witnessed a revolution of football for good. The football became a leather tool introduced to local school playgrounds as a means of encouraging educational attendance, whilst the charitable fundraising power of the sport had confirmed the convictions of those behind the foundation of Celtic. From this point, nothing could stop the founding of Celtic Football Club in November 1887.

It is evident that Hibs played a massive role in Celtic’s birth. The Bhoys were born out of a need to support The Poor Children’s Dinner and Breakfast Tables, and the idea of using football to do so had been explored by Walfrid, Dorotheus, Glass and others. However, Hibs’ fantastic example, encouragement at the triumphant reception in St Mary’s, and assistance at every step was an essential factor in making the dream a reality.

Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 2)

By Liam Kelly 12 January, 2022

https://thecelticstar.com/celtics-complicated-relationship-with-hibernian-part-2/

(Follows from Part 1) That Hibs played a huge part in Celtic’s formation is a fact which has never been denied. But what many people fail to note is some of the differences in the operation of the clubs, which distinguished the pair.

The founding fathers of Celtic didn’t wish to simply imitate Hibernian, they had seen the struggles of over 40 Irish clubs in Scotland and understood that they needed to be the best to survive.

Celtic immediately set about being the biggest Irish club in Scotland. This was proven when the club attracted the star signing of James Kelly from Renton. So influential was Kelly, that the saying went “No Kelly, No Celtic!”

Beyond lofty ambitions to become top dogs, Celtic differed from Hibernian in two key areas (this is not to say Hibernian were not successful or to detract from the achievement of winning the Scottish Cup within 12 years of formation).

Firstly, the club did not enshrine any exclusivist policy, and the first non-Catholic player to enter Celtic Park did so in the Bhoys’ second ever season. That signing was a goalkeeper named James Bell, who joined from Dumbarton in 1890. Bell was a Protestant, who was replaced in 1891 when another man of the same faith arrived at the club. The latter was named Thomas Duff, better known by his nickname ‘The Cowlairs Orangeman’. This was in contrast to Hibernian (in their original form), who insisted that players were practicing Catholics.

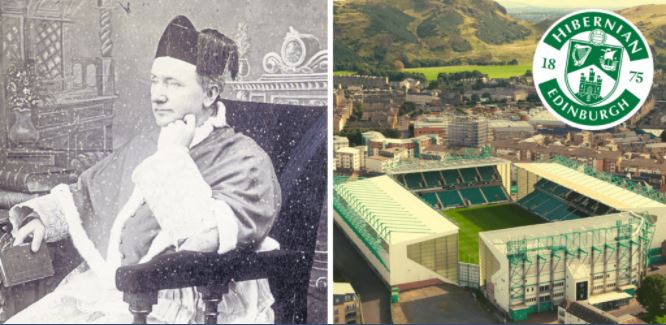

Hibs had been founded by Canon Edward Joseph Hannan and Michael Whelahan in 1875. Hannan was a Limerick man, who had worked to improve the lives of young parishioners in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh and had set up a local branch of The Catholic Young Men’s Society ten years earlier, before becoming a priest at St Patrick’s Church.

READ THIS…Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 1)

Despite starting as a small charitable church team, Hibs were refused entry to Scottish football competitions due to being an Irish club. However, Canon Hannan had done much lobbying to the governing body, which resulted in acceptance of the team eventually participating in the 1877 Scottish Cup, just two years after the club’s foundation.

It is against such a backdrop that Hibernian’s exclusive signing policy has to be set. Therefore, some comments from Celtic fans about Hibs being one of Scotland’s first sectarian clubs can be a little harsh and lacking in context at times. Nevertheless, Celtic Park opening its doors to all people, regardless of their faith, gave the club a more outward looking identity, which Hibs later got on board with.

It is worth noting that Brother Walfrid and his colleagues were actually slammed by Hibernian for choosing the name Celtic. After Hibs’ first game against Celtic on 4 August 1888, an open letter was issued to the media, written by Hibs’ Secretary John McFadden. Part of the text read: “Patriotic Irishmen, truly, the Celtic and its supporters; patriotic Irishmen indeed who, in order to raise the name of Celts – a name which may cover Welsh, Highland Scotch, French, and all the nations of that family – dealt as they thought, and by means which are apparent to everybody, a death blow to the Hibernian club.”

Going on to criticise the “white flag with green crossbar flying triumphantly above” Celtic Park, McFadden turned his attention to the colours of Celtic’s shirt: “The feeling that I had was that the Hibernians did not pretend to be anything else than true Irishmen; who are not ashamed, but proud, to wear the green, and who don’t wear a white shirt and edge the collar with green so that it requires a microscope to detect the colour at all.”

The second notable difference between the early ideals of Celtic and Hibernian concerned politics. Fans of both clubs were vocal supporters of Irish Home Rule, but there was a difference among the respective committees.

Celtic were very publicly supportive of Irish Home Rule. A wanted IRB man (Pat Welsh) was among the founding fathers, convicted Republican Michael Davitt was named as the club’s Patron, and almost every one of the founders was involved in Irish political matters to some degree. In addition to that unified approach, an official Celtic delegation was the only sporting representative(s) at the Irish Race Convention in Dublin, which was designed to plot a way towards Home Rule.

At Hibernian, there was a split regarding the matter of Ireland’s quest for freedom. In 1890, many of the players and officials took part in political meetings and protests during the Home Rule campaign. However, this brought them into conflict with Canon Hannan and the parish church. Consequently, the club was split and committee members were forced to resign. The issues, thought to be centred around the clergy’s fear of matters becoming violent, played a part in the club’s demise.

As an aside, Hibs’ Irish political claim to fame is undoubtedly that James Connolly was a passionate supporter of their club. The iconic Internationalist, Socialist, and Easter Rising leader hailed from the Cowgate. Hibbies should be proud to call him one of their own.

Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 3)

By Liam Kelly 13 January, 2022

Having covered the role of Hibernian in Celtic’s foundation (Part 1), and explored the differences between the clubs in the earliest days (Part 2), this article looks at the demise of the original Hibernian and allegations that Celtic were to blame.

The most commonly heard accusation is that Celtic put the original Hibernian out of business by stealing a number of their best players. Such a claim often goes unchallenged, yet there a number of facts, aspects and hypocrisies that are ignored when broaching the subject.

The first thing to note is that it was not possible to steal a player at the time. Players weren’t employees, there were no contracts, and individuals could play for multiple teams in any given season if they desired. There wasn’t even any official competitions set up, apart from the Scottish Cup, and the majority of matches were friendlies.

The next fact to consider is that five of the six players who played for Celtic after previously being regulars at Hibernian were from Glasgow. They returned to the West of Scotland, no doubt with financial inducements from Celtic. Such underhand payments were illegal, but this practise of ‘shamateurism’ was not invented by Celtic, nor was it a new thing in 1888. Indeed, Hibs were charged with professionalism in 1887 and escaped punishment on a casting vote. In fact, every club outside of Queen’s Park were largely guilty of such conduct.

It is an often forgotten fact that Hibs “stole” six players from Ayrshire club Lugar Boswell during their victorious 1887 Scottish Cup run. Hibernian then replaced the Celtic departees with players from Carfin Shamrock and Whifflet Shamrock – committing the same crime against clubs that Celtic are prosecuted for.

It should be understood that clubs such as Carfin Shamrock were situated in small mining villages. It would not have been financially viable for a football team to operate successfully in that environment in the long run. Therefore, many players understandably moved elsewhere. On a larger scale, this was replicated when the six players swapped the club of the Edinburgh Irish (Hibs) for a more prosperous future at an Irish club with a far bigger community from which to draw support in Glasgow (Celtic). Although, I would contend that Celtic should have steered clear of Hibernian regulars, out of respect for the great role that the Hibees played in our foundation.

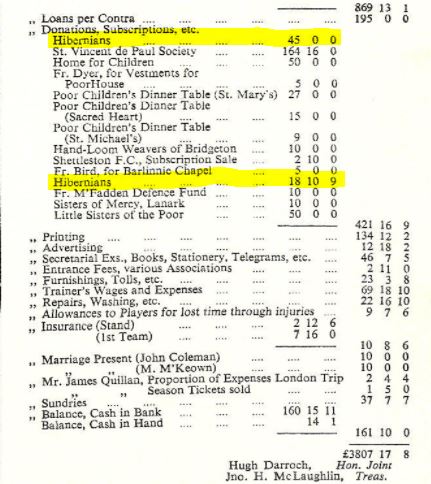

Moving away from the accusations of stealing players and shamateurism, another matter for consideration is that Celtic made two large donations to Hibernian in the Glasgow club’s first season. Not only is this potentially indicative of Hibs being in financial troubles at the time (another reason why players may have jumped ship), but it also suggests that Celtic were not to blame for Hibs disbanding.

Payments to Hibernian on Celtic’s first balance sheet

In terms of the downfall of Hibernian, the key reason for them going bankrupt was that the club Secretary John McFadden absconded abroad with the club’s funds. Furthermore, a disagreement over Irish politics (covered in Part 2) left them with few committee members as conflict between the Church and those in favour of Irish Home Rule caused a split.

Hibernian were resurrected in 1892 and they had a Celtic man to thank in part for that. Thomas Flood, a Celtic member from Dublin, had moved from Coatbridge to Edinburgh by that stage, where he worked as a journalist for the Catholic Herald. While in the capital, Flood helped to resurrect Michael Whelehan and Canon Hannan’s (who passed away in 1891) club. He later returned to Coatbridge, but the role that he and others played had ensured that there was a new Hibernian for the Edinburgh Irish to follow.

To evidence this, Brendan Sweeney’s fantastic Celtic: The Battle For The Club’s Soul books referenced that, at the end of the 1893/94 season, the Scottish Second Division committee held a meeting. During proceedings, the Chairman congratulated Hibernian on winning the title and singled out Thomas Flood for the pivotal part he played in the club’s rebirth.

READ THIS…Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 2)

Sweeney notes the following from the Scottish Sport newspaper at the time: “The Chairman said that the championship had been secured by the Hibernian, and he thought it only right that he should congratulate the club on their splendid performances during the season. He would not think it proper if he did not take that opportunity of saying that he thought a good deal of the success of the Hibs was due to the indefatigable energy of Mr Thomas Flood, the Match Secretary. He hoed there would be no question of Hibernian securing a place in the First Divsion. Mr Flood, who was warmly cheered, said he begged to thank them heartily for their kind expressions. It had always been a pleasure to meet with the gentlemen who represented the clubs in the Second Division, and he could assure them that he was not surprised that they should show their goodwill by congratulating his club on their success.”

Thomas Flood, the @CelticFC member from Dublin who settled in Coatbridge, before work took him to Edinburgh for a few years where he helped resurrect @HibernianFC in 1892, before returning to Coatbridge. pic.twitter.com/HA9C9YHMjC

— CelticEarlyYears (@EarlyCeltic) January 2, 2019

*For the Hibs fans who have commented about the proprietorship of public houses, which John Glass and the Celtic committee were known to entice players with at times; my use of the term ‘financial inducements’ in Part 3 was intended to cover all forms of enticement from monetary offerings to ownership of pubs. To be more specific, this practise of gifting pub ownership did happen for certain star players. If memory serves me correct, this was the case for the likes of James Kelly and Dan Doyle among others.

In regard to the six Hibs players who joined Celtic, Willie Groves was set up with a public house by the club after he had signed and he is listed as applying for license of that premises (29 Taylor St, Townhead) in August 1890. However, Groves would depart for the wages offered by West Bromwich Albion, in England’s professional league, two months later! Michael Dunbar owned multiple pubs, but his licenses appear to have been secured in 1913 when he was a Celtic Director rather than during his playing days. The others – Tom Maley, Johnny Coleman, Michael McKeown, James McLaren – did not own pubs to my knowledge.

Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 4)

By Liam Kelly 14 January, 2022 5 Comments

Celtic and Hibernian have had some tempestuous moments over the last century and beyond. Fact and fiction combine in supporters’ analysis of these moments, particularly where Harry Swan is concerned. This article seeks to redress matters by giving an objective analysis of two key points of contention.

Celtic fans often slander Hibs for their role in the infamous flag controversy of the early 1950s. Additionally, Harry Swan is often described as an anti-Irish bigot but the story is a little more complex than that. Before delving into the character of Swan and that flag furore, it has to be noted that Celtic were guilty of doing Hibs a disservice with a different vote in 1894.

At the end of Part 3 of this series, I referenced the findings of Brendan Sweeney in his books Celtic: The Battle For The Club’s Soul. The article concluded with quotes from the Scottish Sport newspaper when former Celtic member, Thomas Flood, had been congratulated for his role in the rebirth of Hibernian after they had won the Second Division. Flood responded by graciously accepting the praise and stressed that he hoped they would have no issues in being admitted to the First Division. Continuing from the quotes in Part 3, the report went on to state: “He hoped that the Hibs, having by hard work and consistency now won the championship of the Second Division, would be favoured with a sure passage into the First. If they did not, he believed there would be more than his club disappointed, for admission to the senior body was the only thing worth striving for in the Second Division.”

In that era of football, promotion and relegation wasn’t a simple matter. The process meant that the bottom three teams of the First Division went into a ballot with the top three teams of the Second Division, and three of the six teams were admitted to the top flight after all member clubs had their say via a vote.

On 1 June 1894, the Scottish League met and the ballot took place with all members present. The bottom three teams in the First Division were Dundee, Renton and Leith Athletic, whilst the top three teams in the Second Division were Hibs, Cowlairs, and Clyde. Brendan Sweeney, in his aforementioned books, writes: “After the first ballot, Dundee and Clyde were favourites for the First Division and the second ballot confirmed this with an equal share of the votes for both in the top two places of 14 each. Hibernian were forced to drop out of proceedings after the first ballot having only received one vote. This only left one place to be filled and it went to Leith Athletic on 8 points, with Cowlairs on 4 points and Renton on 2 votes. Hibernian’s single vote in the first ballot went to Leith Athletic in the second ballot, but no other votes changed.”

Dundee had been admitted to the First Division the previous season in an effort to improve the standard of the game in that city and they were commended in their efforts in which they finished in eighth place out of ten, so there was no surprise that they were re-elected. However, it was astounding that Hibs weren’t granted entry. To make matters worse, they had only won one vote out of 42! Not even fierce rivals Hearts, who would have reaped the financial rewards of the derby game, voted for Hibs’ admission.

The reasons listed for why Hibernian were not favoured in the vote were many, the main being that a rumour had gathered pace that the club would disband if they were not promoted. The gossip was untrue, but a strong sense of anti-Irishness no doubt motivated others to try and kill the Hibees, while it would also have been galling for many Scots to have two well supported Irish clubs in the top flight. That said, Celtic did not vote in Hibernian’s favour either, so they too take some blame. This was probably because it would help Celtic to maintain their position as Scotland’s main Irish club if they remained in a higher division than Hibernian.

Strangely, Hibs won the League again the next season and did gain promotion that time. The two clubs met in several friendlies that summer and buried the hatchet. The new Hibernian’s first season in the top flight saw them fetch crowds of 17,000 at Easter Road for a meeting against Hearts, with the Hibees playing in front of 20,000 at Celtic Park the following week.

Celtic’s misdemeanour in not lending their vote to Hibs in the 1890s was superseded by the Hibees’ own voting misdemeanour in 1952. It was then that there had been major crowd trouble between Celtic and Rangers at the New Year’s derby. In response to this incident, the Glasgow Magistrates invited representatives of the Scottish Football Association and the Scottish League to consider the following proposals:

1: The Rangers and Celtic clubs should not again be paired on New Year’s Day, when passions are likely to be inflamed by drink and more bottles are likely to be carried than on any other day.

2: On every occasion when the clubs meet admission should be by ticket only and the attendance limited to a number consistent with public safety, the number to be decided by the chief constable.

3: In the interests of safety of the public Celtic F.C. should be asked to construct numbered passage-ways in the terracing at each end of Celtic Park.

4: The two clubs should avoid displaying flags which might incite feeling among the spectators.

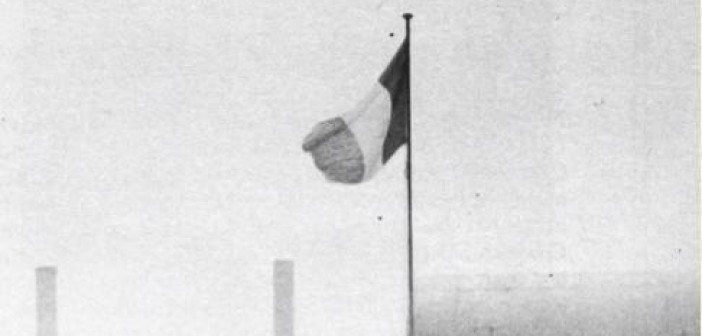

The final point was the one that was taken forth by the SFA, courting immeasurable controversy with its vague wording and likely reference to the tricolour. The national flag of Ireland was, and still is, an essential symbol of Celtic’s Irish heritage. The particular flag flown at the stadium at the time had been handed to Celtic Football Club by the first Taoiseach of Ireland, Eamon De Valera. It was not a gift that would be readily removed.

Knowing the value of Irish identity to Celtic, many fans were concerned that some within the SFA would seize the opportunity to use the recommendations against the club. Those fears were realised when, after consideration, the Referee Committee of the SFA ruled that ‘Celtic be asked to refrain from displaying in its park any flag or emblem that had no association with the country or the sport on match days.’ While expressing dissatisfaction that other recommendations had not been adopted, the Glasgow Magistrates endorsed the decision of the Referee Committee, as did the SFA council (Hibs’ Chairman, Harry Swan was then the acting SFA President), by 26 votes to 7. However, Mr. John F Wilson, Chairman of Rangers, told the council: “The emblem has never been of any annoyance to Rangers. Don’t delude yourselves.” Wilson’s stern contention that the flag of Ireland should be permitted to ripple in the wind above Celtic Park should not come as any surprise. Indeed, for Rangers to prosper they needed that badge of Irishness across the city: a representation of the very thing that their club had become the antithesis of in order to manufacture an identity and attract support.

The Irish flag at Celtic Park

Bob Kelly defended Celtic’s traditions in less than phlegmatic fashion. He claimed that he would rather remove Celtic from Scottish football and start playing Gaelic games at Celtic Park than comply with the order. Kelly felt that to ignore the historical significance of the club would render its existence meaningless. This was not a mere matter of a flag. It was the surface of a wider battle against anti-Irish racism and institutionalised bigotry.

Kelly’s abrasive resistance ultimately led to the flag issue being voted on by all teams in the league. Hibernian voted in support of the SFA, a disappointing move from a fellow Irish inaugurated club. Amid incredible irony, the deciding vote lay in the hands of Rangers. As previously alluded, Rangers had the foresight to consider the financial implications of the situation and determined that they wished for the tricolour to stay at Paradise.

The SFA Council convened a meeting to discuss the outcome of the vote (chaired by Harry Swan), which had favoured Celtic’s stance. Despite the Hoops having a mandate from the rest of Scottish football, the council decided to hold a vote of their own, as to whether they should reverse their ruling on the flag issue. It was a disgraceful mark of the organisation’s bigotry that their internal vote rejected the democratic voice of Scottish football.

The battle lines were well and truly drawn. If Celtic continued to fly the Irish flag in defiance of the SFA ruling, and any misconduct by their supporters took place, then the club would face a fine, closure of the ground, or suspension from the league. As ever, the Celtic board would not give in. Desmond White (Celtic Chairman in the late 70s) commented to The Evening Times: “It is indeed a sad commentary on the bigotry which still exists in the West of Scotland that this flag should be looked upon as an act of provocation. Eire is after all, a friendly country. Many of our supporters are wholly or part of Irish origin and naturally are proud of their Irish ancestry and would have every right to feel slighted if the tricolour was singled out for removal.”

The genuine threat of expulsion hung over the club for the remainder of the 1951/1952 season. George Graham (SFA Secretary, Grandmason, and Orangeman) led attempts to punish Celtic further, a move which Desmond White later said: “Will see him roast in hell.” The bitter clique led by Graham continued to press for Celtic to take down the flag and submit to the SFA’s demands. Celtic had taken legal advice on the matter and were confident about the outcome. However, Graham was not an easy man to tackle with his masonic connections.

Surprisingly, Hibernian Chairman Harry Swan publicly backed the SFA Secretary at this time. The position was largely held because of Swan being acting SFA President. Swan was also thought to be a Freemason himself, but contrary to popular belief in Celtic circles, it appears that he was simply acting to further his personal ambitions and strengthen his relationship with the top brass of the game’s governing body in Scotland.

Indeed, Swan’s masonic links have been assumed to be anti-Irish/anti-Catholic by many Celtic supporters, which would then explain why he wanted Celtic to remove the tricolour. This theory is also assumed, by some Celtic fans, to be the reason behind Swan removing the harp badge from Easter Road. However, a closer examination of the man suggests different.

The large motif on the entrance at Easter Road was lost on demolition due to rebuilding part of the stadium. This destruction was necessary, and it occurred several years into Swan’s tenure. He commissioned works from Ireland for Hibs, including commissioning a new Hibs’ crest to replace the motif that had been lost. This sat in the boardroom at the stadium and upon Swan’s passing, it was gifted to his widow.

Much like Hibernian’s eventual prevailing with promotion in the 1890s, Bob Kelly’s persistence finally paid off when clubs and authorities alike realised that Celtic were not going to budge, and their expulsion would have huge financial repercussions for Scottish football. Speaking to a lay Catholic organisation years later, Bob Kelly stated: “We had no need to be ashamed of our fathers, nor had we any cause to be ashamed that those founders (of Celtic) came from that country that has provided protagonists for liberty wherever they have settled.”

It has been brought to my attention that some Hibs fans on Hibees Bounce forum have been following the series and comments have been very positive thus far. So, thank you to the Hibs supporters getting involved in the stories of our complicated relationship!

Here’s some of the comments:

Liam drifts into the world of player stealing, again pretty fair although no mention of the pubs Celtic supposedly gifted the Glasgow based Hibs players to entice them back, and the the classic old firm whattaboutery of Hibs doing the same thing to other wee clubs. Best appraisal of the early days of our illegitimate offspring written by a Celtic man so far imo.

There are some real gems in this material such as Celtic twice giving donations to help prop up a financially ailing Hibs evidenced with precise details that’s nothing less than outstanding historical research.

The author’s general conclusion that the original Hibs club was racked by Irish political turmoil and factional infighting and financially bankrupt due to the theft of the club funds is very accurate as is his outline description of how “backhanders” and “inducements” paved the way towards early professional football contracts.

There is a Celtic slant to his writing as you would expect but he acknowledges the huge part Hibs played in Celtics foundation I don’t have a problem with any of his conclusions.

Its light years ahead of the “Celtic stole all oor players” garbage you hear from the Hibs pub bores which should have been put to bed years ago as the real story is far more complex, fascinating and interesting.

Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 5)

By Liam Kelly 15 January, 2022 No Comments

The first four parts of this series have covered the historical events between Celtic and Hibernian at committee/boardroom level. Our clubs have been on different trajectories at different points in the last 130 plus years or so. Part 5 is about some of the fallout associated with those differing directions.

It goes without saying that Celtic are now a much bigger and much more successful club than Hibernian. Consequently, many Hibs fans have slapped a ‘glory hunter’ tag on Celtic supporters outside of Glasgow. However, Celtic attracted the support of the worldwide Irish diaspora for a variety of reasons.

The first factor to consider is that the Glasgow Irish community was far larger than the Edinburgh Irish population. As such, Celtic quickly became a bigger supported club. Furthermore, lots of towns in the West of Scotland, such as Greenock, Port Glasgow, Coatbridge and Dumbarton, had (and still have) large multi-generational Irish communities. These people added to Celtic’s organic support in Glasgow as they were particularly drawn to this big (reasonably local) Irish club, whose sizable fanbase was combined with exciting players like James Kelly, who performed in a fantastic stadium.

Certainly, the club’s natural support gave it a great platform from which to build, but the ambition of the founding committee took it to the next level. To lease land for a stadium from a private landowner within a week of the club being formed spoke volumes. Then, to construct that stadium (by a volunteer workforce) of the highest standard within six months was astounding. The original Celtic Park boasted a pitch measuring 110 yards x 66 yards, terracing around three sides of the stadium and an open air stand, capable of accommodating 1,000 spectators, with a pavilion, a referee’s room, an office, dressing rooms and toilet facilities inside.

Celtic’s significant support from inception, its first class stadium, and the enticement of entertaining star players had immediately differentiated the club from parochial sides such as Whifflet Shamrock and many like them. It is unsurprising that people of Irish birth or origin in the West of Scotland flocked to Parkhead over their parish church teams. What Celtic had created was the modern day equivalent of someone supporting a nearby professional club rather than an amateur village team. The fact that the club also gave the Irish community something to be proud of, a place to express their culture and faith, and raised funds for their needy children only strengthened the feelings of adoration.

Celtic Graves Society plaque to mark the site of the original stadium

While continuing to capture the interest of ethnic Irish people in Scotland, Celtic began to secure support in Ireland by visiting the Emerald Isle for a short tour of Belfast in 1889 (within a year of playing their first ever match). The Bhoys’ trips to Eire soon inspired the creation of Belfast Celtic Football Club, which further publicised Celtic’s name across the 32 counties.

The above factors meant that Celtic simply became a bigger club than Hibernian, and thus they were soon seen as the main beacon of Irishness in football. Irish immigrants in the USA (where Celtic first toured in 1931), Canada, and Australia etc. began to support them. They did so because the club was a symbol of their heritage, culture and identity. It is unlikely that many within the Irish diaspora decided that they’d choose Celtic over other clubs with Irish connections (such as Hibs) just because they win more trophies. Instead, and I mean this with no disrespect, Celtic were the main sporting symbol of the Irish diaspora and Hibs were not viewed with as much significance. The enduring support in Ireland and among the global Irish communities continues in this way, though is now more commonly passed down the generations rather than choice being involved. Similarly, as Celtic were quickly viewed as the main Irish club in Scotland, many Scots born Irish descendants also identified with the club more than any other, subsequently bequeathing following generations with support for the team.

Studies into the ethnoreligious make up of the Scottish based Celtic support tend to suggest a very high percentage have ancestral roots matching the club’s own history. Although that fact would indicate that the majority of Celtic fans have a genuine connection to the club, there is a suggestion among Hibs fans that Celtic supporters, when drawing on their Irish roots, are glory hunting – or that they select the Hoops over the Hibees due to the different fortunes of the clubs. This is further assumed to be the crime of Celtic supporters in Edinburgh. However, generally speaking, few Celtic fans, particularly those with an Irish heritage, tend to decide to support the club. Most are born into it; a gift (or curse as some may see it) handed down the generations. Furthermore, there are other factors beyond glory to consider when distinguishing the clubs (which will be covered in Part 6).

Despite what I have written thus far, I am not naïve enough to think that there were originally no Celtic supporters who latched on to the club because it was the most successful team with which they could identify in Scotland, or that Hibs wouldn’t enjoy a bigger support from the Irish community if they had won more trophies. Being a bigger supported club and becoming that main sporting representation of Irishness went hand in hand with success, but it is not as straightforward as fans picking winners, as the previous (and latter) paragraphs hopefully explain.

There is another contentious part to the particular suggestion that those outside of Glasgow, who back the Hoops rather than Hibs, are glory hunters. It should be noted that Hibernian haven’t always been less successful than Celtic. Indeed, Celtic endured an abysmal period beginning at the outbreak of WWII and were almost relegated in 1948. The club then went through a difficult time in the 1950s (minus some memorably unexpected cup triumphs like the Coronation Cup and iconic 1957 League Cup final) and early 60s, before Jock Stein’s arrival heralded a new era of unparalleled success. In those same periods, Hibs were enjoying their golden years.

Hibernian had the likes of Matt Busby and Jimmy Caskie playing for them in the War and then went on to win three championships, 1948, 1951 and 1952, in four seasons. The Hibees also reached the semi final of the European Cup in 1956. That incredible record was largely attributed to the heroics of the Edinburgh club’s iconic forward line of Gordon Smith, Bobby Johnstone, Lawrie Reilly, Eddie Turnbull and Willie Ormond – nicknamed the Famous Five. Excitement continued into the early 1960s as Hibernian regularly enjoyed European football at Easter Road, defeating Barcelona and Real Madrid under the floodlights in the capital. The Hibees’ victory over Barcelona (3-2) at Easter Road in 1961, after recording a 4-4 draw in the Camp Nou, subsequently saw them reach the semi final of the Fairs Cup, before losing to AS Roma in a third match decider at Rome’s Olympic Stadium.

If Celtic fans are mostly glory hunters, then why didn’t they, their ensuing generations, and those from Irish communities swap Parkhead for Easter Road when the Bhoys went through the bleakest periods in their history (40s, 50s and early 60s), while Hibs were at their imperious best in that era? Given that the overall Celtic fanbase remained bigger during that extended time (average match attendances were also similar between the clubs), and also stayed large throughout the miserable 1990s, it leads one to deduce that support for many Celtic fans must be based on more than glory.

On the other hand, Hibernian were almost able to fill half of Hampden for the Premier Sports Cup final this season, yet they only attracted a fraction of that support for the semi final and league games. Therefore, Celtic fans could flip the script and assert that perhaps this could be an argument for glory hunting. For those who indulge in this needless bickering, it certainly highlights difficulties for supporters to pin the tag on others.

Outside of the Irish domain, there are numerous Celtic supporters from various walks of life. As stated, many are born supporting the team. However, some make a choice as they are attracted by political factors, some for football reasons, some find a connection to Celtic through their faith, some take inspiration from Celtic’s long held inclusive signing policy, some live in Glasgow and prefer the club to any other in the city, some were introduced to Celtic by their friends or family, some grew up in close proximity to Celtic Park. Like most football clubs, the list is endless. To label them glory supporters would be quite presumptuous as well.

Contentions that the faithful are glory merchants is one aspect of the digs between fans of each club. Sometimes this is banter, but at other times it can become quite vitriolic. Regardless, it is far from the only jibe heard.

One of the common wind ups thrown Celtic’s way is the remark: ‘if it wasn’t for the Hibees you’d be current buns’. This comment is probably not something with much serious thought behind it, but it is not rooted in any historical reality either. The song refers to the huge helping hand that Hibernian had in Celtic’s formation (covered in Part 1), assuming that if the Hibees didn’t help Celtic to come into existence then our fans would have supported the other big club in Glasgow – Rangers. Ignoring the fact that Queen’s Park were actually the biggest Glasgow club at the time, there was little chance of the city’s Irish community supporting Rangers. A Catholic was not signed at Ibrox for almost two decades, and a prominent Conservative/Unionist and freemason who made a public stand against Irish Home Rule (John Ure Primrose) was named Rangers Patron in 1888; dispelling the myth that the influx of Loyalist workers to Govan’s Harland & Wolff shipyards was the catalyst for Rangers adopting a sectarian signing policy. In that sense, the truth is probably a better wind up. Before Celtic arrived, the Irish community in Glasgow supported Hibernian from afar. Reports of the time suggest that they were delighted at the Edinburgh Irishmen’s Scottish Cup victory in 1887. So, in reality, if it wasn’t for the Hibees we would be Hibees ourselves!

Another bit of banter aimed at Celtic fans is the fact that Hibernian wore the hoops first. That statement is absolutely true, not that many Celts are concerned by it. But the claim, which sometimes accompanies this statement, that Celtic stole Hibs’ kit, is not accurate. Celtic did not become the Hoops until 1903, some 15 years after the club played it’s first match. The Bhoys’ first kit saw the players don a white shirt, adorned with a Celtic cross set against a red circle on the breast. It also had green on the collar (as mentioned in Part 3, this was something Hibs’ Secretary John McFadden slammed Celtic for as the kit was not Irish enough). In 1899 the kit was changed to vertical green and white stripes, a harp being emblazoned on the breast, before the hoops finally emerged. Alongside these kit changes at Parkhead, Hibs ceased to wear hooped jerseys as of 1879 – before Celtic were even formed.

*For the Hibs fans who have commented about the proprietorship of public houses, which John Glass and the Celtic committee were known to entice players with at times; my use of the term ‘financial inducements’ in Part 3 was intended to cover all forms of enticement from monetary offerings to ownership of pubs. To be more specific, this practise of gifting pub ownership did happen for certain star players. If memory serves me correct, this was the case for the likes of James Kelly and Dan Doyle among others.

In regard to the six Hibs players who joined Celtic, Willie Groves was set up with a public house by the club after he had signed and he is listed as applying for license of that premises (29 Taylor St, Townhead) in August 1890. However, Groves would depart for the wages offered by West Bromwich Albion, in England’s professional league, two months later! Michael Dunbar owned multiple pubs, but his licenses appear to have been secured in 1913 when he was a Celtic Director rather than during his playing days. The others – Tom Maley, Johnny Coleman, Michael McKeown, James McLaren – did not own pubs to my knowledge.

Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 6)

By Liam Kelly 16 January, 2022 2 Comments

Part 5 challenged some of the narratives perpetuated by supporters when it comes to Celtic and Hibernian. This article touches on aspects of those narratives again, by looking at the complexity of the different identities expressed by fans of the two clubs. Given that both share a similar history, it is perhaps surprising to see how differently that history manifests at Celtic Park and Easter Road, respectively.

When looking at the identity of Celtic and Hibernian fans, there are two things that immediately stand out. The first is that celebration of Irish heritage is much more prominent among the Celtic faithful than the Hibs support, and the second is that a considerable section of the Celtic fanbase are known for political expression, whereas Irish Republican songs have not featured in the Hibernian songbook since the late 1970s.

It makes sense to begin any analysis of identity by looking at the development of the communities for which the clubs were formed. It is a very complex topic, so cannot be covered in full comprehensivity in this article, but I hope to provide a basic synopsis.

The Edinburgh Irish assimilated into Scottish society in the first half of the 20th century. This was partly because the community was small in size, partly because intermarriage made it indistinguishable, and possibly because the lived experience of the Irish diaspora on the east coast was not always one with the same intensity of sectarianism and anti-Irish racism as that experienced by their counterparts in the west. Accordingly, Hibs began to lose a strong sense of Irish identity and, generally speaking, its supporters began to look upon Ireland as a distant connection, with the main relevance being a historic nod to their founding fathers. A few tri-colours can be seen dotted in the stands, and the club’s crest has featured a harp since the turn of the millennium; a balance between being a Scottish club and having Irish roots which most Hibs fans seem comfortable with. However, these developments have led to Celtic supporters hitting them with the jibe of being ‘soup takers’ (people who converted for food during the Famine) due to a perception that the Hibees have abandoned their Irish heritage or ‘taken the soup’ if you will. Unsurprisingly, this cold remark is seldom well received.

In terms of the Glasgow Irish, they were much larger in number which has enabled the community to persist. Another wave of Irish immigration to the city in the 1920s maintained the link too. In regard to intermarriage, although this continues to occur at an increasing rate today, historically it wasn’t as prevalent as in other parts of Scotland. This comparative lack of mixed marriages also played a considerable role in the perseverance of Irish identity. Meanwhile, the level of sectarian bigotry and anti-Irish racism demonstrated in the west (though far from exclusive to the region) has impacted immensely. Indeed, occupational parity was not achieved by the Irish and their descendants in Glasgow (under the age of 55) until 1991. When extended to cover the entire working population (under 65s), parity was not achieved until 2001! Those socio-economic barriers, combined with a number of Orange marches taking place in the region, the historic presence of an anti-Catholic fascist razor gang in the city (The Billy Boys) and bigoted songs by a nearby club’s sizable support (such as the Famine Song), all played a further part in the Glasgow Irish holding their ethnic background dear in an unwelcoming host environment.

The Irish were once de-humanised and depicted as apes in the press

In the context of Celtic, the supporters’ sense of Irish identity has strong cultural relevance. Music and song provided the link to home for the first exiled Irish men and women, something that was evident on the slopes of Paradise and among Brake Clubs from the earliest days. Naturally, that musical heritage was handed to the successors and has never stopped being enjoyed by the faithful. It is not only a celebration of those who founded the club, but a celebration of many within the support’s own familial history.

On the point of cherishing heritage, whilst the Celtic support is vast, studies have repeatedly shown that the majority of fans hail from Irish stock. One ethnoreligious survey in Glasgow put the number at 74%. This leaves room for many fans from outwith the Irish tradition, but an overwhelming number do have ancestral connections to the Emerald Isle, meaning that the cultural ties go beyond the founding fathers of the football club and extend to the fans’ own roots. Quite poignantly, a certain interrelatedness can be found in this respect because of the community for whom Celtic was primarily founded. With that in mind, common references to the Celtic support as “plastic paddies” are somewhat disappointing to hear from Hibees.

At Hibernian, the support is not derived from the Irish diaspora to the same extent. As a speculative figure, there have been unscientific estimates suggesting that 50% of Hibs fans hail from Irish extraction, with a smaller percentage attaching significance to that ancestry. Geography has probably played a greater role in luring fans to Easter Road over the years, the simplistic generalisation being that those north and east of Princes Street tend to support Hibs, as opposed to those in the south and west of the city favouring Hearts. Therefore, it is unsurprising that Irish culture isn’t as prominent among the Hibernian fanbase as it is at Celtic Park.

External factors impact upon identity too. For example, in comparison to Hibs, Celtic enjoys huge support from the global Irish diaspora and across Ireland itself. These people solidify ties to the country. However, the most influential cohort from a historical perspective has been those who previously followed Belfast Celtic until the Ulster club’s demise in 1949. It was then that Paradise was lost in Antrim and found in Glasgow. As a result, Celtic inherited the sole allegiance of a fervent support, who would soon become politicised by the emergence of the Civil Rights movement and the unfolding of the Troubles. Celtic was to become their social outlet, and a place to freely express themselves, as the Flags & Emblems Act had criminalised Irish identity in the statelet known as Northern Ireland. The presence of so many Belfast Celtic fans, and subsequently their descendants, at Parkhead added to the eminence of Irish culture and further radicalised an already politically minded diaspora.

The matter of politics is probably the biggest chasm between the identities of Celtic and Hibernian. In the early years, Hibs fans were keenly supportive of Irish Home Rule. As the situation in Ireland changed through the Tan War, partition, civil rights protests, and armed struggle for a reunified Republic – songs of rebellion could be heard at times inside Easter Road. These songs were sung intermittently in the 1970s, but were dropped by the Hibs support after the bombing campaign against economic and military targets made its way to mainland Britain. No doubt the media coverage (or lack of) of events throughout the political conflict also affected things.

By contrast, Irish rebel songs continue to be heard by sections of the Celtic support to this day and are a major part of the matchday experience on supporter’s buses and in pubs. The reasons for this are many. The freedom of Ireland was never far away from the mind’s of those involved in Celtic’s beginnings. The likes of William McKillop (Irish Parliamentary Party MP for North Sligo and South Armagh) and Patrick Welsh (IRB volunteer on the run) were among the founding fathers, whilst Michael Davitt (famous Irish Patriot and convicted Republican) was named Club Patron and was invited to lay the first sod of turf at the new Celtic Park in 1892. During said turf laying ceremony, God Save Ireland, a controversial rebel song of the time, was performed by its composer T.D Sullivan. This was nothing unexpected as songs of an Irish Nationalist nature were sung by committee members at functions, and Celtic were the only sporting organisation to send an official delegation to the 1896 Irish Race Convention in Dublin, which was designed to plot a route towards Irish Home Rule.

Those same Nationalist songs, A Nation Once Again, Wearing of the Green, and the Dear Little Shamrock, were sung by supporters on the terraces and aboard Brake Club carts before being passed down the generations. With a keen eye on the ancestral home, the Irish diaspora were inspired by the main cause moving from Nationalism to Republicanism and the quest for Home Rule being replaced by outright independence after the Easter Rising. The Scots-Irish were enraged by the undemocratic partition of Ireland (as they saw it), just a few short years after the majority of the country had demonstrated its desire for an independent 32 County Republic in the 1918 general election. Witnessing six counties being torn from the other 26, Irish national sovereignty and democracy being violated, incensed those among the diaspora. Meanwhile, the subsequent pogroms, internment, and the Special Powers Act being inflicted upon Northern Nationalists did little to quell their boiling indignation as the new state violently rumbled through its infancy.

It must be remembered that there was another wave of Irish immigration to Glasgow in the 1920s (time of partition). These immigrants particularly came from border counties such as Donegal, Sligo, and Cavan. Anti-partition feelings were very strong in those regions of Eire and Eamon De Valera, President of the Irish Republic from 1919 to 1922, once remarked: “The financial contribution to the Irish struggle from among the Scottish communities was in excess of funds from any other country, including Ireland.” To reinforce this point, Glasgow and the West of Scotland boasted more Republican volunteers and Sinn Fein members than Belfast in the 1940s!

The politics, songs and culture of Ireland continued to be inherited by the offspring of Irish immigrants. After the Civil War ended across the water, 50 years of discrimination against Northern Catholics in housing, voting and employment rarely went unnoticed. The emergence of the Civil Rights movement, followed by the Battle of the Bogside, burning of Bombay Street and long struggle for a United Ireland, radicalised the Irish around the world to varying degrees. Throughout these times the ongoing presence of Ulster based fans at Parkhead, and the Glasgow Irish experience of discrimination mirroring the oppressive hardships endured (to a lesser extent) by those in the North of Ireland, made songs about these events feel relevant to the Celtic faithful.

Political songs were once the mainstay of the Celtic songbook, but since the mid-90s they have become the preserve of the away support and small pockets at home games. Those who sing them would contend that Irish Rebel songs tell the story of the struggle for Irish freedom, commemorate patriots, and remember the hardships endured by the Irish over the years. Famous musician Derek Warfield, in his Celtic & Ireland in Song and Story book, describes them in the following way: “These historical songs and ballads have been used by the Irish people to defend and propagate the many related causes of Ireland. They have been known to educate and inform, to bring knowledge and truth through literature and poetry. Above all, the lyrics and tunes in Celtic & Ireland in Song and Story (which are sung by the Celtic support) are far reaching, educational, and of course, provide a great source of pleasure.”

For a considerable section of Celtic fans, rebel songs were and are the foundation of Irish identity and rebellion, whilst they combine with non-political Irish cultural songs too. This has caused disagreements within the support, has outraged unsympathetic people in the Irish Free State, and has coveted a lot of controversy in Britain. Although these songs do not contain sectarian literature in their lyrics, they are believed to be sectarian songs by many in Scotland. More accurately, they remember and laud those who are viewed as terrorists by most in British society. To explain why sections of Celtic fans (and the Irish diaspora around the globe) disagree with such an opinion, even if they share a disdain for some of the individual actions undertaken by the organisations they sing about, it would require an analysis of Irish history, delving into the policy of Ulsterisation and suchlike, which is impossible to suitably provide here. Political websites or books would be more appropriate platforms for such complex content to be digested, and to get a greater insight into the accurate nature of the recent conflict in Ireland, but suffice it to say that the Hibernian support and sections of the Celtic support differ somewhat on the matter!

Politics is one of the distinct things about Celtic, probably the main differentiator between the identity of the Hoops and the Hibees, and is the reason why the club’s Irish based support is more concentrated in the North of Ireland. In that sense, away games are probably more reflective of a subgenre within Irish culture, with the home matches reflecting the type of folk songs that the wider Irish population may enjoy – the likes of the Fields of Athenry, Let The People Sing, Lonesome Boatman etc. It is also important to point out that politics in Paradise are far from limited to Ireland. Indeed, an extension of the Republicanism among Celtic fans has seen visible displays regarding other Anti-Imperialist causes (the plight of the Palestinians), Socialist matters and Labour politics.

Many Hibs supporters don’t want to be associated with the baggage of the above mentioned controversy, which in Scotland, is generally viewed as being part of an ‘Old Firm’ feud. As such, there has been a reluctance from some Hibees to display the Irish tricolour or to celebrate the club’s Irish roots at times. Indeed, such expression is often incorrectly conflated with sectarianism, whilst some people have become fearful of the stigma associated with it. That wider Irish culture isn’t always distinguished from politics or sectarianism is a sad indictment of Scottish society. Meanwhile, it is also saddening that many believe celebrating one’s own Irish roots is somehow anti-Scottish. This bemusing position has created a perception that the majority of Celtic fans view themselves as Irish rather Scottish, and is, anecdotally speaking, another reason why some Hibs fans don’t want to be tarred with this brush.

In an extensive study by John Kelly at the University of Edinburgh, titled Hibernian: The Forgotten Irish?, it was particularly dispiriting to read comments from Hibs fans accusing the Celtic faithful of being bigoted for flying the Irish flag and, without a hint of irony, suggesting that waving tri-colours should not happen at Easter Road because it is an intolerant action.

Conflicting identities in the modern day reached a moment of great strain when the Hibernian faithful proceeded to boo the Fields of Athenry and the Soldiers Song during the 2013 Scottish Cup Final against Celtic. There are still some Hibees who are less than phlegmatic about their desires to maintain the relevance of the club’s Irish background without the politics, but for the national anthem (as sung in its original form and by the Easter Rising leaders before anyone comments) and an inoffensive song about the famine (an intrinsic event to formation of our clubs) to be disavowed suggests disparity between the supports. From shared history to divided present indeed.

Celtic’s Complicated Relationship With Hibernian – (Part 7)

By Liam Kelly 17 January, 2022 No Comments

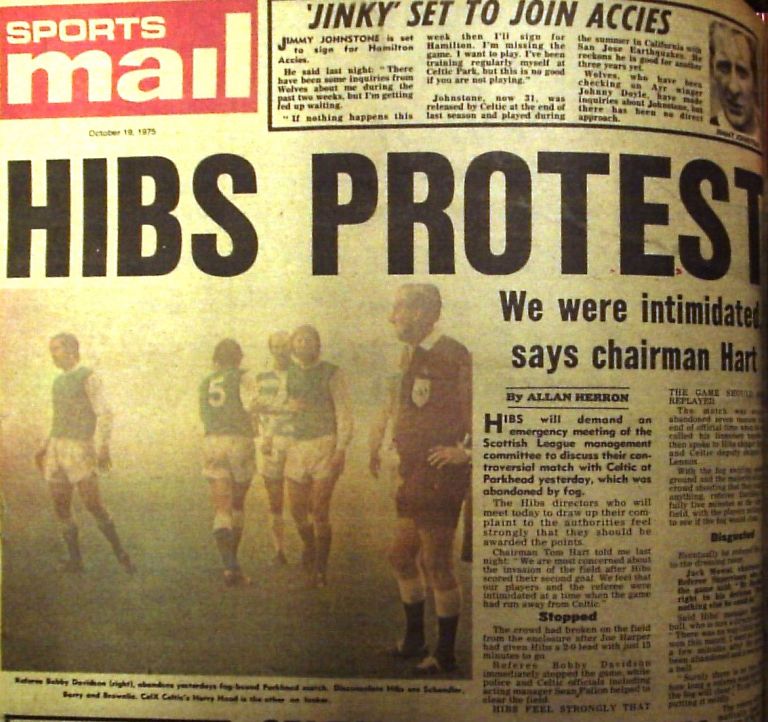

Matchday looms tonight and thus this series is drawing to a close. In this penultimate article, we rewind to the 1970s for an incredible incident which angered Hibernian and helped the Celts. In all the cracking Celtic v Hibs encounters over the years, this event has largely been forgotten. However, it is one occasion when there can be no doubt that the Hibees were right to feel aggrieved with Celtic.

Glasgow was buried beneath a blanket of mist for two days prior to 18 October 1975, yet the game against Hibs went ahead at Celtic Park. The Hoops would have been glad to play, considering that they were unbeaten in their last ten matches in all competitions. Sean Fallon had really got his Celtic side on song, after initially struggling when he took over the reigns from Jock Stein, who sat out the season due to a serious car crash in early July.

Ten minutes into the match, Celtic probably wished that the match was in fact called off. A Pat Stanton inspired Hibs team dominated proceedings and were making things difficult for the Bhoys. The dominance of the Edinburgh side was reflected on the scoreboard in the 26th minute, when Des Bremner put the visitors in front after capitalising on a poor back pass by Johannes Edvaldsson. The Hibernian attacker couldn’t believe his luck as the ball fell at his feet; he rounded Peter Latchford and slotted into an empty net.

Thick fog quickly descended, prompting fans at either end of the stadium to chant to one another, so as to inform fellow supporters of the unfolding action. One need not imagine the polite nature in which the Jungle described a missed opportunity to supporters housed at the opposite end of the stand.

Play continued and the visitor’s lead was deservedly doubled by Joe Harper in the 76th minute. The goal was reportedly an absolute peach, which silenced Celtic Park. Along with the silence, increasing mist fell across the stadium. Fans began to wonder, ‘could the conditions save Celtic at this late stage?’ To their shame, some frustrated supporters in the Jungle took the opportunity to force things in the Hoops’ favour. Unbeknown to the referee (Bobby Davidson), behind the thickening layers of fog, several Celtic fans had leapt the barrier and entered the field of play. Davidson was preparing for the restart when he looked to his horror as faint silhouettes revealed themselves in his peripheral vision. The police immediately pursued the pitch invaders, whilst Sean Fallon also left his dugout to assist in clearing the field.

Alarm bells were ringing in the mind of the referee, but play did eventually continue. A further nine minutes elapsed without Celtic posing any threat to the Hibernian defence. It was looking like two points dropped for the Hoops, which would put a dent in their quest for the title. Although, Rangers would remain level on 11 points due to their 2-1 loss v Motherwell at Fir Park that day, victory would send Hibernian top with 12 points.

In the 85th minute, the unthinkable happened. Bobby Davidson put the whistle to his mouth and abandoned the match due to the worsening fog. The Celtic support cheered the great escape as if they had scored a last minute winner. By contrast, the incensed Hibees’ winger, Alex Edwards, headed to the Jungle as a matter of priority. When faced with the vociferous Celtic support, he presented them with a less than warmly received V-sign gesture!

In the wake of the abandonment, Hibs launched a protest, demanding that the Scottish League Management Committee convene a meeting to discuss the issue. Their wish was granted a day later, on 19 October 1975, when Hibs directors voiced their complaints to the Scottish football authorities. The Capital club’s Chairman, Tom Hart, is noted as saying: “We are most concerned about the invasion of the field after we scored our second goal. We feel that our players and the referee were intimidated at a time when the game was running away from Celtic.” The Hibernian delegation went on to demand that the points be awarded their club’s way. However, it wasn’t to be. The view taken by the Scottish League was that awarding the points would be an entirely presumptuous position to take, as Celtic could theoretically have equalised in the short time that remained.

Few could have complained in the Celtic camp if the points were taken, though they were certainly not going to decline the opportunity to replay the match at Celtic Park seven weeks later. The replay took place on Wednesday 10th December. By this time, Celtic were joint top of the table with Motherwell on 20 points, and two points in front of third placed Hibernian. It comes as no surprise that Hibernian were out to reclaim the points robbed in October, particularly as victory would move them into pole position. The Hibees started fast, forcing Peter Latchford to make a number of saves in the Celtic goal. Twice Latchford denied Pat Stanton, before clutching a Des Bremner header, which was bound for the top corner. However, the shot-stopper was eventually beaten in the 45th minute, when Ian Munro chipped a pass out wide to Arthur Duncan. The winger caught the Celtic keeper by surprise when he shot from the by-line, but Parkhead breathed a collective sigh of relief as the linesman correctly raised his flag to signal for offside.

Celtic dusted themselves down during the break and Fallon’s men returned to the field a different proposition. On the stroke of 60 minutes, Harry Hood played a driven pass into the feet of Dixie Deans at the edge of the box. Just when it appeared that the forward would be tackled, he stabbed a low shot past Jim McArthur in the Hibernian net. The majority of the 33,000 crowd were sent into delirium.

Celtic’s joy was short lived, as in the 72nd minute, Tom Callaghan clashed with Alex Edwards, resulting in a Hibernian free kick. Eric Schaedlar looped the set play into the penalty area and Latchford came to claim the ball. Unfortunately, Edvaldsson in the Celtic defence, ignored the call of his keeper and thrust his head into the mix. A goalmouth scramble followed, with Joe Harper getting the telling touch to equalise. The balance of play was very even thereafter, and the two teams remained locked at 1-1. The point was enough to put Celtic clear at the top of the table, overtaking Motherwell by the most slender of margins. They could thank their lucky stars, or perhaps the foggy dew for that!

From Celtic The Early Years by Brendan Sweeney

Hibs historian laments ‘disastrous effect’ of Celtic in 1880s

http://local.stv.tv/edinburgh/magazine/226800-hibs-historian-on-the-disastrous-effect-from-founding-of-celtic/

By Graham Fraser 25 May 2013 12:49 BST

Facebook Tweet Google

New team: Celtic in the late 1880s with many former Hibs players in the side.Scottish Football Museum

When the players of Hibs and Celtic run on to the Hampden pitch on Sunday for the Scottish Cup Final, they will only have one thing on their minds.

For Celtic, winning the trophy will be the culmination of a successful season that has seen the Glasgow giants retain the league title and qualify for the last 16 of the Champions League, Europe’s elite football competition.

For Hibs, lifting the Scottish Cup would bring an end to 111 years of pain for their supporters, all of whom have waited all of their lives to sing Sunshine on Leith in Easter Road while the players hold the trophy in the air.

But Hibs and Celtic are more than just opponents in this year’s showpiece event. Their histories are linked all the way back to the days when Celtic were formed in 1888.

“If there hadn’t been a Hibernian FC there certainly wouldn’t have been a Celtic FC,” comments Alan Lugton, a Hibs historian who has published three books on his team entitled The Making of Hibernian.

Alan, who has watched the Easter Road men for over 60 years, looks back to a period when he believes Hibs went from being a major force in British football to a shadow of its former self due to the ambitions of Celtic, the new kid on the block.

In the 1880s, with football an amateur pursuit of players, Hibs played a number of a charity matches across Scotland to raise money for those in need.

Alan contends a key moment in the club’s history, and Celtic’s, occurred in September, 1885 when a second string Hibs side took on a team brought together under the banner Glasgow Hibs. The proceeds of the match went to poor children living in Glasgow’s East End.

One of those who helped those children was Brother Walfrid. Many Celtic fans will recognise this figure and the founder of their club, the subject of a statue outside Parkhead, and Alan, who used to work as an international air freight supervisor at Edinburgh Airport, believes this match was the event that Brother Walfrid decided that Glasgow, with its much larger Catholic population, should have its own team to raise money for those in need.

Hibs went on to win the Scottish Cup in 1887, attracted a crowd of 12,000 to a charity match against Renton in Glasgow that year, and would go on to become ‘World Champions’ after defeating English FA Cup winners Preston North End.

Alan said: “1887 was the climax for Brother Walfrid. 12,000 at a game was quite incredible.

“Brother Walfrid was saying surely, in Glasgow, we can get a team together along the same lines as Hibs to do all this good work.

“There was final meeting of Brother Walfrid and his colleagues on the 6th of November 1887 and they formed a football club. Brother Walfrid got his own way and the football team were called Glasgow Celtic.”

Another man thought to be at that meeting was John Glass. The Irish businessman and others, Alan argues, had a very different outlook for Celtic.

The author added: “While Brother Walfrid was looked upon as the founding father, a lot of the people in the background were Irish Glasgow businessmen, particularly John Glass.

“They had a different view of how this new club were going to be. It wasn’t going to be along the lines of Hibs, a church amateur team. They were going to have a professional team as professionalism was on the horizon. They had this vision, and they weren’t going to be interfered with.”

Hibs, quite happy to see another Irish team in Scotland, opened Celltic’s ground with a match against Cowlairs in 1888 but Glass was already looking forward.

“Glass and his cohorts were eyeing up the Hibs players who had been on loan,” said Alan. “He wanted to poach these players.

“In the summer, they made payments to six Hibs players who were amateurs. Willie Groves – probably the greatest football player Scotland has ever produced – James McLaren, Paddy Gallagher, Mick McKeown, John Coleman and Mick Dunbar.

“They were six members of a fantastic Hibs team. There was a bitterly humorous thing said at the time – ‘When these men were with Hibernian football club, they played only for faith and Ireland. When they went to Celtic, they played for 30 shillings’.

It would be eight years until Hibs would make another real mark in the Scottish game, finishing runner up in the 1896 Scottish Cup.

Celtic, meanwhile, grew quickly and won its first Scottish Cup in 1892 and its first Scottish league championship the following year. The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

“It had a disastrous effect on Hibs,” said Alan.

“It left Hibs in a terribly weak position with the rise of Celtic and their immediate popularity.

“They (Celtic) were able to get all the up and coming Irish lads in the west of Scotland. There was bitterness, but Hibs didn’t want to see a division in the Irish camp in Scotland.

“Hibernian Football Club was the pride of the Irish in Scotland. They were the premier team. They won the Scottish Cup and put the Irish in Scotland on a public platform.

“With Celtic’s rise to success, they had an immediate impact and they became the dominant Irish team.”

Of course, very little of this history will matter to the 22 men who run out to the cheers of 52,000 supporters in Glasgow on Sunday.

For Alan though, who will be in the crowd with his wife for the game, the history matters.

Whose grass-roots are the greener?

https://www.scotsman.com/sport/football/whose-grass-roots-are-greener-2476259

Those of a Hibernian persuasion are all too aware that history is against them. They recently celebrated the 99th anniversary of their most recent Scottish Cup win – Glasgow wags say that next year will be the centenary.

By The Newsroom

Sunday, 20th May 2001, 2:00 am

If Hibs players and fans are seeking inspiration, they could do worse than turn to their club’s long history, not least in their role as innovators. They were the first Scottish club to play in the European Cup, for instance, and first to arrange shirt sponsors.

There is also much history linking Celtic and Hibs, and the Edinburgh team are senior partners in developing the Irish influence on Scottish football. But the argument about who stole who and what from whom has yet to be resolved, finally.

Sign up to our Football newsletter

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Sitting last week in the fine new Scottish Football Museum which is largely his creation, director Ged O’Brien effortlessly recalls early spats between Hibs and Celtic, and makes important points about that interconnection with Ireland. Born in north Cork, but raised in Southampton, he is an expert on such diverse subjects as Venetian art and American architecture, but football has always been “the most important thing” in his life.

Hence his permanent move to Glasgow 13 years ago after years of travelling north to watch matches. Next week sees the opening of the museum at Hampden, the culmination of his crusade to build a facility that he says will entertain and educate, and explain a significant influence on the world game. “Scotland invented the running and passing game that underpins all modern football, so in a real sense we can say that Scots invented football.”

O’Brien reels off the countries where Scottish coaches taught the populace to play – Brazil and most of central Europe, apparently – and shows off the world’s oldest surviving trophy, a ticket for the first international match and a display featuring the first world champions – Renton FC from Dunbartonshire. Long since defunct, Renton beat West Bromwich Albion, champions of England, to claim the title in 1888.

But other, perhaps sinister, events of that year still rankle in Sunny Leith, because that was when Glasgow Celtic came into existence, largely by poaching the best players from Hibs, Renton and other teams.

O’Brien ventures: “If I was a Hibs fan, which I’m not, and I had a long memory, I would be saying that we were responsible for the birth of you Celtic guys, given that you stole most of our team, especially when we were only trying to help you by coming over to play at Cowlairs, and isn’t it a shame that Brother Walfrid [the Celtic founder] didn’t mind his own business?

“Then, in the early 1890s, the Celtic board was split, and some of them went off temporarily to form Glasgow Hibernian. Guess which Edinburgh club they got their players from?

“Funnily enough, there had been attempts to persuade Hibs to move to Glasgow prior to Celtic starting. Had things not gone differently, it might well have been Glasgow Hibernian which won the 1967 European Cup.”

In football, as in the country generally, the Irish sometimes had it rough in Victorian Scotland, the fledgling Scottish Football Association refusing to allow Hibs to join because they were “only for Scotchmen”. O’Brien recalls: “But Hearts had already clocked that there was money to be made in playing Hibs, so they got them into the Edinburgh FA, and that made it a fait accompli that Hibs would join the SFA.”

O’Brien suggests that it should be a matter of pride to their fans that the first Irish club in Scotland were Hibernian of Edinburgh, and they certainly had one of the Emerald Isle’s notable figures among early supporters – socialist leader James Connolly. “If he heard that Hibs had lost, he was absolutely sick for the weekend,” adds O’Brien.

Connolly was the son of Irish immigrants, and the influx meant that there were enough Irish people in Edinburgh to create Hibs in 1875. “The team was sectarian – you had to be a church-going Catholic to play,” O’Brien confirms. “But sectarian in those days obviously meant something completely different. Journalists wrote that what Dundee needed was a sectarian team, like its brothers in Edinburgh and Glasgow, and they used the term like they were talking about niche markets – clubs that satisfied the need for a local populace in the cities which would not support the existing teams because of their associations. It was only after the First World War, when sectarianism really got going, that the term took on a different, darker meaning.

“Hibs had already thrown off sectarianism as far back as 1893, when anybody was allowed to join the club. But they kept their culture, though they have gone through periods of questioning exactly what they stood for. For instance, when the harp was removed from the club crest in the 1950s.”

O’Brien contends that the duality of the two clubs has led to much soul-seaching in recent years, and he feels that Hibs are happier with their culture. “For some years now, Celtic and Hibs fans have been asking themselves, ‘Can we have an Irish tradition without being accused of being IRA sympathisers and anti-Scottish?’

“I’ve seen the new Hibs crest [the harp was re-introduced last year] and it looks to me as though they are comfortable with all the strands of their tradition – it has Leith, Edinburgh and Ireland in it.