Coaching Staff | Previous Coaching Staff | Players | Managers | First Team Squad | Jimmy Hogan – “Right Man, Wrong Time”

Details

Fullname: James Hogan

aka: Jimmy Hogan

Born: 16 October 1882

Birthplace: Nelson, England

Died: 30 January 1974

Celtic coach: 1948-50

Ref: Legendary seminal coach who changed the face of football on the continent

The Legendary Coach…

The Legendary Coach…

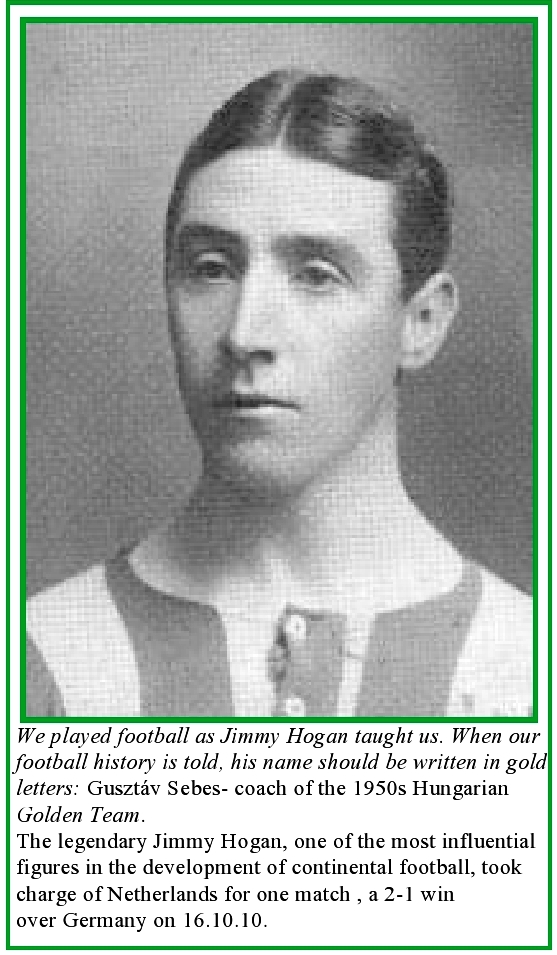

“We played football as Jimmy Hogan taught us. When our football history is told, his name should be written in gold letters”.

Gusztáv Sebes, Hungarian footballer, coach and national team manager

Pioneering football coach Jimmy Hogan was brought to Celtic Park in the late 1940s by the then chairman Robert Kelly.

Perhaps sensing that Celtic’s post-war lack of direction and general state of decline needed radical attention, Kelly viewed the veteran Hogan as an experienced yet innovative coach who was capable of reviving the struggling Hoops. Kelly had enjoyed success with a similar move over a decade earlier when he had brought former player Jimmy McMenemy back to Parkhead. Now, as Celtic entered a new decade, he hoped Lancashire-born Hogan would be a catylst for a much needed change of fortune.

The manager at the time Jimmy McGrory was one of the greatest ever Celtic players and viewed universally as a thoroughly decent and genial man. However he lacked real authority as a coach and didn’t exert a great deal of discipline upon his players. Indeed he very rarely featured in training sessions. Celtic were at a low point and actually missed relegation quite narrowly in recent seasons. The old days of continual success was well behind and the club was in a poor state on the pitch.

When Jimmy Hogan arrived in 1948 he was viewed as one of the finest coaches in world football. A man who could help spark the Celtic team and fire them back to the glory days. He had earned a great European reputation in Austria and Hungary (priorly a great forward thinking nation in football).

But the arrival of Hogan wasn’t the success story Bob Kelly had hoped for. The majority of the players, especially the more senior players, viewed Hogan’s appointment with extreme scepticism and, at times,mocked his methods. Hogan though, ever the gentleman persevered and it became obvious during his short stay at Celtic that he commanded a lot of respect from the younger players there.

Men like Charlie Tully, never the greatest trainer himself, are said to have thought very highly of him, and Tommy Docherty who later went on to manage Scotland and Manchester United, credited his success to the initial school of coaching he received from, as he puts it “The finest coach the world had ever known”. He also described various players’ attitudes as follows: “It was in the days of Charlie Tully and players like that, and they looked upon coaching as a bit of a joke.” Many players wasted the valuable resources in front of them.

Many Celtic historians believe that Hogan arrived at Celtic a little too late to have made any real impact. He was in his late `60s when he came to Glasgow. Previously he had a reputation for being a strict disciplinarian and a man that wouldn’t be crossed. That had waned more than a little upon his appointment at Celtic and the players who just a few seasons earlier had flirted with the very real prospect of relegation, didn’t want to know about Jimmy. It would be the middle of the next decade and the arrival of Jock Stein before the winds of change truly swept through Celtic Park.

Possibly, Jock Stein learned one set of valuable lessons more than others from Jimmy Hogan. Players were at times children and had to be bullied at times (a method in madness) for their own sake. The lack of an iron fist from the club coaching and management meant that the players did not buckle down and learn from this great man. We can only guess now how things could have been so much different if they had paid more attention to him.

Had Jimmy Hogan arrived 10 years earlier or had the players been more receptive to his methods, the course of Celtic’s history may well have been altered. Sadly Jimmy Hogan remains a small footnote in Celtic history. In the history of football however, the name Jimmy Hogan remains as one of the true legends of the game but sadly it won’t be for his time at Celtic.

Grave & Remembrance

In October 2021, a remembrance was held for Jimmy Hogan with a new gravestone laid in respect of him. A badge of each club he had roots with is also engraved on the back of it, which we are all proud to see.

Articles

Books

Articles

Independent on Sunday: Football: Prophet or traitor? How the mastermind behind the Magyars became an outcast in his homeland

Independent on Sunday, The (London, England)

November 16, 2003

Author: Norman Fox

With the memorable exception of 1966, when Alf Ramsey inspired an unremarkable but highly motivated England to win the World Cup, the birthplace of organised football has consistently failed to make a serious impact on the global game. The recent European Championship qualifying draw in Turkey showed commendable spirit but little real artistry or imagination. That has been the story for much of the past 50 years.

On 25 November 1953, a crowd of 100,000 peered through the Wembley murk to see England fall to their first home defeat by Continental opposition. Hungary’s victory was bad enough, a humiliating 6-3, but the margin in skill with the ball could be measured in decades. Those were the decades in which a little Lancastrian, Jimmy Hogan, had been coaching abroad and constantly warning that football in his homeland was about to be overtaken by the more technically proficient sides he had long been teaching. Hungarian players had appreciated and benefited from his instruction even before the First World War, and at the end of the triumph in London the visiting delegation dedicated the victory to him. Their association’s president, Sandor Barcs, said: “He taught us everything we know about football.”

Over the years, occasional references to Hogan in football’s literature have suggested that on that salient day he sat with the VIPs in the Royal Box. In reality the 70-year-old, who was still coaching Aston Villa’s junior players, organised a coach trip for them to see the game. He said they would witness something out of the ordinary, by which they thought he meant that England would demolish the Hungarians, as did most of the press of the time.

Hogan had long tried to convince English administrators that their football had gone backwards. Ball skills, he said, had been lost in kick-and-rush. The Football Association’s detached, superior attitude meant that they failed to recognise “the shining example of the coaching profession” as the West German team manager Helmut Schoen later described him. In his youth, Schoen had been coached by Hogan at Dresden FC.

Hogan’s presence at Wembley made England’s defeat doubly embarrassing. The England captain, Billy Wright, never one to exaggerate, said: “There were people there that day who were of a mind to call him a traitor.” It was not for the first time.

In a remarkable life which had begun as one of 11 children born to Irish parents who moved to Lancashire to find work in the cotton mills of the 1880s, Hogan honed a natural aptitude for skilful football that nevertheless led to only a comparatively modest career with Burnley, Bolton, Swindon and Fulham, where he came under the influence of an artistic group of Scottish players. He formed the opinion that, by and large, English football failed to promote ball skills and had no trust in those players who mastered them. It was true then, and remained so.

In the early part of the last century he went with Bolton on a summer tour of Holland, where they overwhelmed Dordrecht. He promised himself that one day he would go back and teach them technique. He kept his vow, and in his early thirties became the youngest English coach ever to work full-time on the Continent, starting at Dordrecht. His reputation both as a teacher (his favourite description of how he thought the game should be played was “on-the-carpet football”) spread throughout the Continent.

He was talking about a form of Total Football generations before the Dutch and Germans of the Johan Cruyff and Franz Beckenbauer era; he encouraged correct diets, persuaded cynical senior professionals to get together before games in what is now called “bonding”, and whereas in England the cloth-capped “trainers” continued to insist that a player deprived of the ball all week would be all the more hungry for it on a Saturday, he made sure that almost all training was done with one.

His work took him to Austria, where in partnership with Hugo Meisl he created the foundation of the great “Wunderteam” who astounded England with their skill at Stamford Bridge in 1932 when losing by only 4-3. Then to Hungary, where his inspirational work spawned the “Magic Magyars” who beat England. He worked in France, Germany and even Africa, where in the 1930s he predicted that one day “these players will shock the world with their skill”. But in addition to coaching thousands of players and discovering talented ones on local parks, his life was an adventure.

Shortly before the start of the First World War he was coaching in Austria but was told there was no need to worry about returning home to England. It was poor advice. On the opening day of war he was arrested and thrown into prison. He was released but interned, working as a gardener, odd- job man and tennis coach (he was of national standard himself) for two British businessmen who were married to Austrians. On his return to Britain he was almost destitute, but heard that football people who had fallen on hard times could apply to the FA for a benefit of pounds 200. He went along but the secretary, Frederick Wall, offered him only a pair of khaki socks. “We gave these to the boys in the war and they were very grateful,” he told Hogan. The clear message was “traitor”.

A few years before the Second World War began he had to get out of Germany quickly and escaped into France with his family’s life savings sewn into his plus fours. On his return to England he managed Aston Villa and Fulham and was the subject of a press campaign to be made England manager after the 1953 debacle. But at heart he remained a coach of rare influence. Tommy Docherty, whom he taught at Celtic, said: “It was in the days of Charlie Tully and players like that, and they looked upon coaching as a bit of a joke. But Jimmy was a fantastic man. I was amazed by his practical ability. Even as an old man he could still hit a bucket from 30 yards. He was a very religious Roman Catholic, he never swore. His arrival at Celtic Park was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

He says: ”A lot of people were shocked when Hungary beat England in 1953. But I wasn’t.

”Jimmy, who originally came from Nelson outside Burnley, hadn’t been a great player. But when he hung up his boots he got involved in coaching through the FA in England and did well.

”He went over to coach in Hungary before he came to Celtic. He coached Puskas as a boy and told us how some of his players didn’t have so much as a pair of boots. But they wanted to learn.”

Equally, Ron Atkinson, who was a junior player at Villa, said: “His coaching was revolutionary at the time. We did everything with the ball, which was foreign to coaching in those days. You talk about people being ahead of their time, well he was certainly that. People called him Uncle Jimmy. You always looked forward to being in his group. I can’t remember him ever once raising his voice, but he got all of the respect.”

The great Irish winger Peter McParland recalls that Hogan carried on coaching at Villa Park until he was 76, and “even at that age he could do anything with the ball except make it talk”.

Hogan died in 1974 aged 91. Tributes poured in from all over the Continent, but in England his achievements remained largely unrecognised.

`Prophet or Traitor?’ by Norman Fox is published by The Parrs Wood Press at pounds 9.95 ( 0161 226 446). You also can purchase the book from Independent Books Direct (0870 800 1122).

Jimmy Hogan – The Parson

by The ShamrockPosted on 05/10/2021

https://the-shamrock.net/2021/10/05/jimmy-hogan-the-parson/

“He never forgot the Hungarians. Neither did any of us. But unlike us, at least Stein was in a position through the years to pursue the hope that he could field a team which would bear comparison with them. The green and white hoops of Lisbon were not shaped precisely on the model of the cherry shirts that had swarmed all over England thirteen and a half years before, but Puskas, Hidegkuti and company put a gleam in Stein’s eye and an ideal in his sights that stirred his imagination, and that in itself was to rub off on anyone who would put boots on for him at any stage.”

Jock Stein – The Definitive Biography by Archie MacPherson

England 3 Hungary 6. It was renowned as ‘the match of the century’. It was the first time that England – the country that had boasted for so long of ‘gifting’ football to the world – had been defeated at home by a foreign country (other than Ireland and the home nations). It was a day that shook the sport of football across the globe as the traditional British approach to the game the English air of superiority was ripped asunder by a passing game shaped by tactics and strategies. This was a new dawn.

Jock Stein was at Wembley that day in November 1953 to witness a football revolution which would radically shape his own views on how the game should be played. He was Celtic captain at the time and attended the game with his team-mates as a thank you from the club for that summer’s Coronation Cup success. Many of those Celtic players present at Wembley had previously been coached at Celtic Park by the very man who was credited with creating Hungary’s style and success – and changing the direction in which football was going.

“We played football as Jimmy Hogan taught us” said the Hungarian coach Gusztav Sebes. “When our football history is told, his name should be written in gold letters.” Hungary was not alone in owing a debt of gratitude to Jimmy Hogan. He was credited with helping Hugo Meisl shape the famous Austrian ‘Wunderteam’ of the 1930s. The German coach Helmut Schoen, the man who led West Germany to World Cup success in 1974, had been taught by Hogan and described him as “a shining example for the coaching profession.” As recently as 2008, in his ground-breaking book on the history of football tactics Inverting the Pyramid, the writer Jonathan Wilson described Hogan simply as “the most influential coach there has ever been.”

That is quite a legacy for a man whose association with Celtic is little-known in the modern era.

Born in 1882 in Nelson, near Burnley, Lancashire to Irish parents, Jimmy Hogan was to prove an unremarkable footballer. He had defied the wishes of his father to take up professional football rather then enter the priesthood, although he remained a devout Catholic throughout his life and earned the nickname of ‘The Parson’ from team-mates who were surprised at his aversion to drinking and swearing.

He was a skilful inside-right who made his way through the local semi-professional ranks to Burnley FC aged 20. He demonstrated a commitment to training and self-improvement that helped him win a move to Fulham, which was key to later developments: “My football knowledge improved tremendously at Craven Cottage where I found myself amongst the great Scottish players who were playing the style I had been longing for.”

The Scottish style – which had been pioneered by Queen’s Park in the 1870s and 1880s – favoured quick, short passing in preference to the long-ball and overtly physical approach traditionally adopted by most English clubs. Hogan’s time at Fulham was successful, winning promotion and making it to an FA Cup semi-final in 1908, before a knee injury side-lined him. While he attended Mass one Sunday he received a tap on the shoulder – it was two directors from Bolton Wanderers who (after Mass was over!) enticed him to return home to Lancashire.

He spent 4 years at Burnden Park, helping the club win promotion in his last season, but it was a pre-season tour to Holland that led to him being invited – aged 28 – to cross the North Sea to take up a coaching position there. He was considered to be the youngest British coach to have worked abroad by that time and Hogan attacked his new career with a missionary zeal. In 1912 he was offered a position – via a referee friend – to assist the Austrian national team in their preparations for the Olympic Finals in Sweden. The Austrians made it to the quarter-finals and the head of the Austrian FA, Hugo Meisl, offered Hogan a full-time job to work with clubs in the Austrian capital and prepare the national team for the 1916 Olympics. Hogan did not hesitate and had no regrets: “To leave my dark, gloomy, industrial Lancashire for gay Vienna was just like stepping into Paradise.”

The Great War interrupted, leaving Hogan with his wife and child stranded in Vienna where he was arrested as a foreign national. In early 1915, the British Government arranged safe passage home for his family while, a year later, Hogan was allowed to leave Austria for Hungary where he took up position as coach of MTK Budapest. He set about establishing a coaching template: mastery of basic ball skills throughout the team; emphasising ball control and passing over physical endurance; using effective passing – both short and long – to retain possession and undermine the opposition rather than relying on dribbling wingers, kick-and-rush and the high ball; and moving away from the restrictive tactical formations of old to consider new roles for key individuals in the team.

Success was instant: his team won two league titles in succession playing the ‘Scottish style’ that Hogan advocated. MTK would go on to win an incredible 9-in-a-row and establishing themselves as Central Europe’s most successful team. Hogan returned home to England to be re-united with his family in 1918, yet the Hungarians were grateful for the lessons he had taught.

His achievements as a coach had been ignored at home and after an incident in which he felt he’d been branded a traitor by the Secretary of the English FA, Hogan headed back to the mainland. Switzerland was his next destination where he coached Young Boys of Berne and Lausanne and helped the Swiss national team prepare for the 1924 Olympics in Paris (where they reached the quarter-finals). A return to Budapest followed (where MTK were now known as FC Hungaria and still dominant) before Hogan moved on to Germany in the late 1920s where he led the highly successful SC Dresden (which featured Helmut Schoen) before being appointed as an adviser to the German FA. This job saw him conduct massive lecture tours around the country espousing the doctrine of the passing game, the importance of learning and developing skills (which he adeptly demonstrated) and the significance of strategies in winning matches.

1930 saw Jimmy Hogan depart Germany for brief spells in Paris and then Lausanne before he returned to Vienna to work with Meisl once again. The Austrians, known for their short passing style and tactical innovations such as an attacking centre-half, went on a 14 game winning streak between 1931 and 1932 which led to them being labelled the ‘Wunderteam.’ They headed to the 1934 World Cup in Italy as favourites but were knocked out by the host nation (and eventual winners) by a single goal in a controversial semi-final tie in Milan.

Spreading the football gospel

At last, there was recognition for Hogan in his homeland later in 1934 when he was appointed the manager of former club, Fulham. This time at Craven Cottage was to prove less happy with players resistant to Hogan’s attempts to change their playing style. He was sacked after only 31 games in charge while in hospital recovering after an operation. He returned to the Austrian fold and was in charge of the Wunderteam at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin where they made it to the final – only to lose again to Italy. This was followed by the offer of another hot-seat at a leading English club in the shape of struggling Aston Villa.

The Birmingham club had been relegated from Division 1 the previous season. When Hogan took charge in November 1936, at the age of 54, he faced an uphill struggle in persuading the existing team of the value in adopting a close-passing game. Villa finished 9th that season but the following year it was a different story. Hogan’s teaching and intensive training brought about a transformation. Villa won the Second Division by four points from Manchester United and also made it to the FA Cup semi-finals. On their return to the First Division, Hogan led his team to a comfortable mid-table position of 12th. When war brought the next football season to a crashing halt, Villa decided to terminate Hogan’s contract. Despite his relative success he had failed to win over a Chairman who had once told him: “I’ve no time for all these theories about football. Get the ball in the bloody net, that’s what I want.”

Jimmy demonstrating his skills at an FA training course, 1939

It appeared that Jimmy Hogan’s days as a coach and football missionary were finally over. During the war years he moved back to Lancashire and joined the backroom staff in his hometown of Burnley. Now in his 60s he was happily winding down and back with his family after his extensive travels stretching over three decades. Yet football was forever in his veins. In 1947 he accepted an offer from Brentford, who were languishing at the bottom of the Second Division after losing the first four games of the new season. He helped stabilise the team and they ended the season in mid-table safety. There was another club out there who were in dire need of Jimmy Hogan’s assistance though.

Season 1947-8 had been the worst in Celtic’s history. The team went in to the last league game of the season knowing that a win against Dundee was required to stave off the very real threat of relegation for the first time. Manager Jimmy McGrory intending on resigning if the game was lost. A 3-2 victory and other results in Celtic’s favour meant that humiliation was avoided. It was agreed though that drastic action was needed, having finished in joint 12th position with Queen of the South and four points above relegated Airdrie. In practice, this meant that Jimmy McGrory ceded control over team selection to Chairman Bob Kelly – who had no football playing or management experience to speak of – and that a full-time coach would be appointed to improve the playing squad.

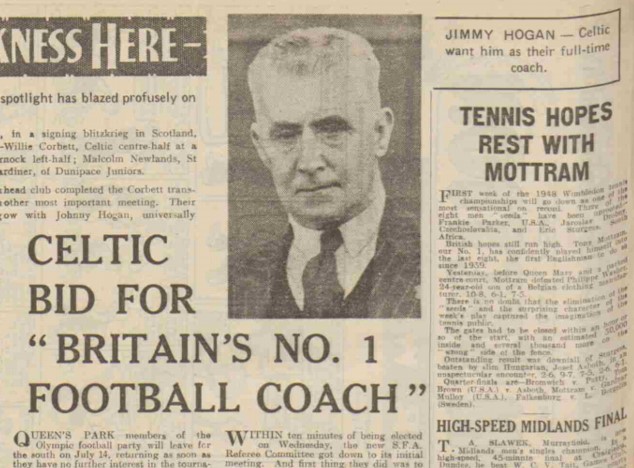

Celtic make their move for Hogan

Celtic could not be faulted in the choice that they made. The Hogan pedigree was second-to-none. He had long advocated elements of ‘the Celtic way’ of playing football, accentuating skill and passing over brawn and relentless high balls. The Daily Record of 5th August 1948 reported: ‘Make no mistake about it, Jimmy is Scots by football adoption and has come here on a year’s contract to help Celtic re-discover their traditional style of play.’ It certainly felt like something of a homecoming for Hogan: “I feel at last that I have come hame. I’ve mixed with Scots footballers ever since I kicked leather and such has been my admiration for their play that I have come to think of myself as a Scot.”

He was realistic to appreciate that there might some resistance to his appointment among the experienced first-team players, as he’d come across at Fulham and Aston Villa, and that his age (he would turn 66 a few months later) was a factor working against him, noting that among the squad he had felt “as if each and every one was saying ‘what can this old codger show us?’” Tommy Docherty was a reserve player for Celtic at the time and recalled that at the first home game the new coach had “sat us down in the dressing room and said: ‘This is the day the good ship Celtic will be launched.’ One of the players quipped in response: ‘You’ll find there’s a few passengers.’ Once again, it would not be plain sailing for the Burnley man back in British football.

He threw himself into the job with vigour. As well as coaching the first-team squad, he was involved in scouting for new talent and also took the reserves for specialist training too, as he’d done at other clubs, realising that his football philosophy worked best on those who were not already imbued with the worst of professional attitudes and habits. In young players like Docherty, outside-left Johnny Paton and inside-forward Jimmy Sirrel he found willing pupils who became advocates of the Hogan approach. Docherty still remembers the Hogan philsophy: “He used to say football was like a Viennese waltz, a rhapsody. ‘One-two-three, one-two-three, pass-move-pass, pass-move-pass.’ We were sat there, glued to our seats, because we were so keen to learn.”

Charlie Tully, newly arrived from Belfast Celtic, recalled how the players got the “surprise of their lives” when their new coach was “the great Hogan . . . probably the greatest football brain in the world.” Arriving two weeks before the start of the 1948-9 season “he promptly doubled our schedule. We got all the ball play we needed but we still had to do our programme of lapping and staminal building exercises. Suddenly, all the slackness stopped. Jimmy Hogan was here for a purpose.” Years later Celtic’s Cheeky Charlie could still chant the Hogan mantra: “At all times play football. Rather lose possession than make a faulty pass.”

The impact was immediate. By early September the Glasgow Herald reported that Hogan’s influence could be seen in the changed playing style of the team: “Most of their players are now obviously following a pattern of thought which seems to lay down as a basic principle that constructive football will, in the long run, pay handsome dividends.” A 3-1 victory over Rangers in the League Cup saw Bobby Evans and Charlie Tully run the show in midfield. Tully put on an incredible display of skill, the Glasgow Herald noting that at one point “the Irishman beat three would-be tacklers in the space of as many yards, and each time by a different manoeuvre. His ability was tantalizing.” His colleague Johnny Paton remembered the moment Tully announced his arrival in Scottish football well: “Tully would put his foot on the ball and virtually invite two Rangers players to take it off him. Then he sidestepped them both. He gave Hogan credit for perfecting that technique.”

Cover Star – v Morton, 1948

Attendances were up significantly and the defeat of Third Lanark in the Glasgow Cup Final at the end of September before a crowd of 87,000 suggested that a corner had been turned, as Celtic historian Tom Campbell noted in his book Glasgow Celtic 1947-70: “For Celtic and the supporters, the trophy was the tangible proof that the side had finally broken through after the war. It had been a long wait but most of the crowd, a record for the tournament, were confident of even greater success in the near future.”

Hogan was credited with being influential in the signings of Bobby Collins and Bertie Peacock who would go on to prove great Celtic servants. He persuaded Bobby Evans that his future lay in midfield rather than as a forward and within two months Evans had won international honours and went on to become a legendary half-back for the club. He felt that Tommy Docherty had the makings of an excellent half-back also but he could not persuade Bob Kelly – as opposed to manager McGrory – of this. Docherty soon left Celtic for Preston North End where he played with distinction for 9 years before joining Arsenal, winning 25 Scotland caps in total: all in the position of half-back. As goalkeeper Johnny Bonnar said: “There was only ever one god in Jimmy Hogan’s time and that was Bob Kelly . . . It was very hard in that era to become continental-orientated. This is to take nothing away from Jimmy. Jimmy Hogan was a very good coach but limited by all sorts of factors at Parkhead.”

As well as Bob Kelly having final say on team selection and player development, Hogan met with resistance from senior players who were not impressed with his coaching credentials or the sight of a white-haired old man showing them where they had (clearly) been going wrong – these after all were the players who almost relegated Celtic. Centre-forward Frank Walsh later confirmed in the excellent Eugene McBride book Talking With Celtic: “You know, John McPhail, Pat McAuley, Jimmy Mallan, they wouldn’t listen to him.” This was a squad that needed discipline as well as coaching, yet there was no-one in authority at Celtic Park prepared to assume that responsibility.

There was no doubt that, for all of Jimmy Hogan’s amiable persona, his age was a sticking point with some of the established Celtic players – as were some of his frequent sayings and the strange practices he indulged in. “We don’t need a gardener here at Celtic Park – our football will cut the grass with the ball” was a popular Hogan phrase which would be met with wry smiles. “Keep the high balls low” was another. The Huddle is now a Celtic institution yet it was first introduced to the club by Hogan with somewhat mixed results, as Tommy Docherty recalled in 2003: “These days we see players huddled together – bonding they call it – in the middle of the field before the game; well Jimmy Hogan used to have them do that in the dressing room before we went out so it didn’t cause any embarrassment on the pitch.”

Jimmy’s Catholic faith was by no means unusual at Celtic Park but his observance of it caused some consternation among the players. Sean Fallon’s debut against Clyde was marked by an own goal but it was not the only memory that the big Sligoman retained of that game. In the changing room before the game started Jimmy Hogan “was going round the players, and I felt something wet on the back of my neck. I looked up, you know, but Jimmy had moved on. I looked at Tully and Tully looked back at me. “Don’t worry”, he said, “it’s only holy water.” Jimmy’s holy water didn’t do me any good that day, I can tell you.”

Jimmy McGrory’s biographer John Cairney noted that Hogan had “the disconcerting habit of frequently blessing himself” and he would also perform a prayer over the Celtic goalkeeper’s hands before the team took to the field. Making the sign of the cross on each player’s forehead – regardless of their religious affiliation – was another practice that even the Catholics in the first eleven found peculiar. In Johnny Paton’s view “He seemed incapable of realising or accepting that the playing staff was not entirely Catholic. He talked as if they were and expected them all to go along with his religious beliefs. In that respect he was very naïve. You can’t expect a whole group of footballers to go to Mass with you – but he did.” Paradise was not the pious place that The Parson anticipated.

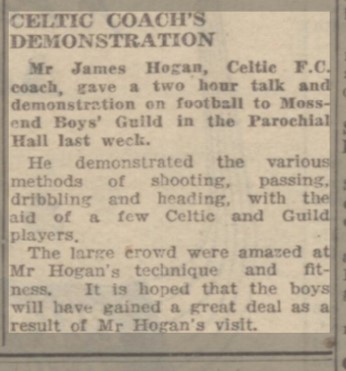

There was little doubt that Jimmy Hogan left a favourable impression on the younger Celtic players of the time however. As well as dedicated training sessions, he encouraged them to accompany him on his visits to Celtic supporter clubs and youth clubs where, in the role of the evangelical, Hogan expounded his theories on football – and gave dynamic demonstrations of the art. Many were left in awe at this elderly gentlemen whose ball skills, even in his late 60s, were jaw-dropping. In Johnny Paton’s view “He probably was a better passer of the ball than Charlie Tully – and Charlie was our most gifted player by far.”

Mossend gets the Hogan treatment

Tommy Docherty remembered the nights well: “I used to chip the balls up and he would trap and pass. His accuracy was magnificent. From thirty or forty yards he could hit a bucket – wonderful skill.” These events proved popular with the Celtic support. Frank Walsh remembered one night out in Govan where the Celtic coach added a song taking the mickey out of Rangers to his repertoire: “Hogan was a great turn, he used to really get the audience going.”

At the end of the two seasons that Jimmy Hogan spent at Celtic Park there was little significant improvement in the team’s performances. Relegation did not threaten again but finishing sixth in season 1948-9 and fifth the next season, while failing to capture any major trophies, suggested this was a squad of players who were not prepared to listen and learn from a living legend. From that squad at Celtic Park, only four individuals went on to have a have a career in the game when their playing days were over: Docherty, Paton, Sirrel and Fallon. The Hogan influence would prove obvious in at least three of them.

Jimmy Hogan returned to Brentford for a short time and then took over the youth team at Aston Villa. The football writer Brian Glanville recalled attending a Hogan coaching session in a London school in the early 1950s where he was again showing off his skills – while wearing a Celtic tracksuit. He was offered the post of Republic of Ireland manager by the FAI, but his missionary days were over. He attended the ‘Match of the Century’ at Wembley in 1953 in the company of some of the Villa youth players – and turned down an invite to a celebration lunch the next day with the Hungarians, instead taking a coaching session with the youngsters back at Villa Park.

In the fifteen years that followed Hogan’s departure, Celtic won only 5 major honours in total including 1 league title. Jock Stein was captain when four of those trophies were captured and he, with Sean Fallon and Bertie Peacock, exerted an influence on the team’s structure and tactics that the club’s management remained incapable of. When he returned as Manager in 1965 and insisted on taking control of team selection from Bob Kelly, Celtic reached heights that had never previously been imagined. Jock Stein never did forget the flamboyant Hungarians who were taught the art of pure, beautiful, inventive football by Jimmy Hogan.

———-

Footnote Jimmy Hogan’s last game as a Celtic coach was a friendly away to Lazio in Rome in May 1950. This most religious of footballing men was part of the Celtic party which enjoyed a Papal audience, as Jimmy told the Scottish Catholic Observer: “We were a matter of only a few yards from the Pope. When the Celtic team was announced he looked at us directly and blessed us all.”

The Parson (front left) visits the Vatican with the Celtic squad

Jimmy passed away at the age of 91 in 1974. For his 90th birthday his family took him on a surprise visit to Turf Moor to see Burnley for what would prove the last time. Even then, Celtic were still in his thoughts, as he told a local reporter who had visited the Hogan family home to cover the birthday celebration: “I am very keen on the League just now, because Celtic and Aston Villa, of which I was both coach and manager, are my favourite teams after the Clarets.”