| Songs and Anthems | Legends and Supporters |

Lyrics

#It was far across the sea,

When the devil got a hold of me,

He wouldn’t set me free,

So he kept me soul for ransom.

Chorus 1

na na na na na na na na na

na na na na na na na na.

I’m a sailor man from Glasgow town,

I’ve roamed this world round and round,

He’s the meanest thing that I have found,

In all my days of wandering.

Chorus 1

And I could see his evil eyes,

It was then he took me by surprise,

Take me to your paradise,

I want to see the Jungle.

Chorus 1

Chorus 2

Here we go again,

We’re on the road again,

We’re on the road again,

We’re on our way to Paradise,

We love the jungle deep,

That’s where the lion sleeps,

For then those evil eyes,

They have no place in Paradise.

Chorus 3

Graffiti on the wall just as the sun was going down,

I seen graffiti on the wall ( Up the CELTS, Up the CELTS),

Graffiti on the wall it says we’re magic, we’re magic,

Graffiti on the wall….I see graffiti on the wall……..

And it says

Ooh ah up the Celts, say ooh ah up the Celts (x5).

We went through each jungle deep,

For the Paradise that we did seek,

Was no trip for the weak,

We’re waltzing with the natives.

Chorus 1

From the Amazon to Borneo,

From Africa to Tokyo,

To the darkest jungles of the world,

But nowhere could i lose him.

Chorus 1

Around in circles every way,

He turned to me and he did say,

I think your leading me astray,

I want your soul me Bhoyo!

Chorus 1

Chorus 2

Chorus 3

With the devil spittin blood,

He said welcome to my neighbourhood,

I’d lose him if I could,

But he was always there beside me.

Chorus 1

He took me back to Glasgow town,

Around the world around and ’round,

The Celts were playing at the Rangers ground,

So I took him up to Ibrox.

Chorus 1

While Mingling with the crowd that day,

I lost him along the way,

You can see him to this very day,

Cheering for the Rangers!

Chorus 1

Chorus 2

Chorus 3#

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ddlRl2AetZ4

Background

“Celtic symphony is not a rebel song, it’s a song about Glasgow Celtic”.

Wolfe Tones (2023) link

It’s a song by the popular Irish celtic folk group “The Wolfe Tones“, which was written around the time of Celtic’s centenary season (1997/98).

It tells the story of a Glasgow sailor possessed by the devil who travels the world trying to exorcise himself from the Devil.

The version generally sung and printed on this page is the popular version. Usually it is just the two choruses 2 & 3 that you will hear being sung on the terraces.

The song began to gain popularity around 2010 or 2011 (via the Green Brigade) before being widely sung by the support on the terraces.

Admittedly the original has a line that some find contentious and is mostly avoided, and so an amendment used as above is “Ooh ah up the Celts” which is the standard amongst most Celtic fans. With all due respect, discussion on that line (and any connotations etc) is left for a more appropriate forum than this one.

However in October 2022, the Irish women’s football side got into hot water over singing the song. After defeating Scotland 1-0 in Glasgow, the players were celebrating in the changing rooms singing the original version of the song with the original contentious line. Worse was the forced apologies made and having to answer to British media who questioned their knowledge of history [sic!], which was quite offensive. More detail in articles below.

The backlash actually led to the song racing up the singles sales charts (if anyone by this point in modern music history even still cared about them). It reached No.1 in the Irish Charts and no.8 in the UK, and up to no.2 in the iTunes UK charts, so ended up making the song even more popular (ironically held off the top spot by a song by ‘Queen’ (the band))!

Articles

Note: All views in these articles below do not necessarily reflect those of this site or any editors/moderators. This is all posted here for reference, and any discussion on related issues (social & political) are best left for a more appropriate forum.

Irish team being ‘persecuted and bullied’ for singing ‘ooh ah up the ‘Ra’, songwriter says

Wolfe Tones member Brian Warfield says he was not necessarily referring to the Provisional IRA in his lyrics

https://www.irishtimes.com/ireland/2022/10/12/irish-team-being-persecuted-and-bullied-for-singing-ooh-ah-up-the-ra-songwriter-says/

Expand

Ireland players celebrate following victory over Scotland at Hampden Park on Tuesday. Photograph: PA

Ronan McGreevy

Wed Oct 12 2022 – 21:17

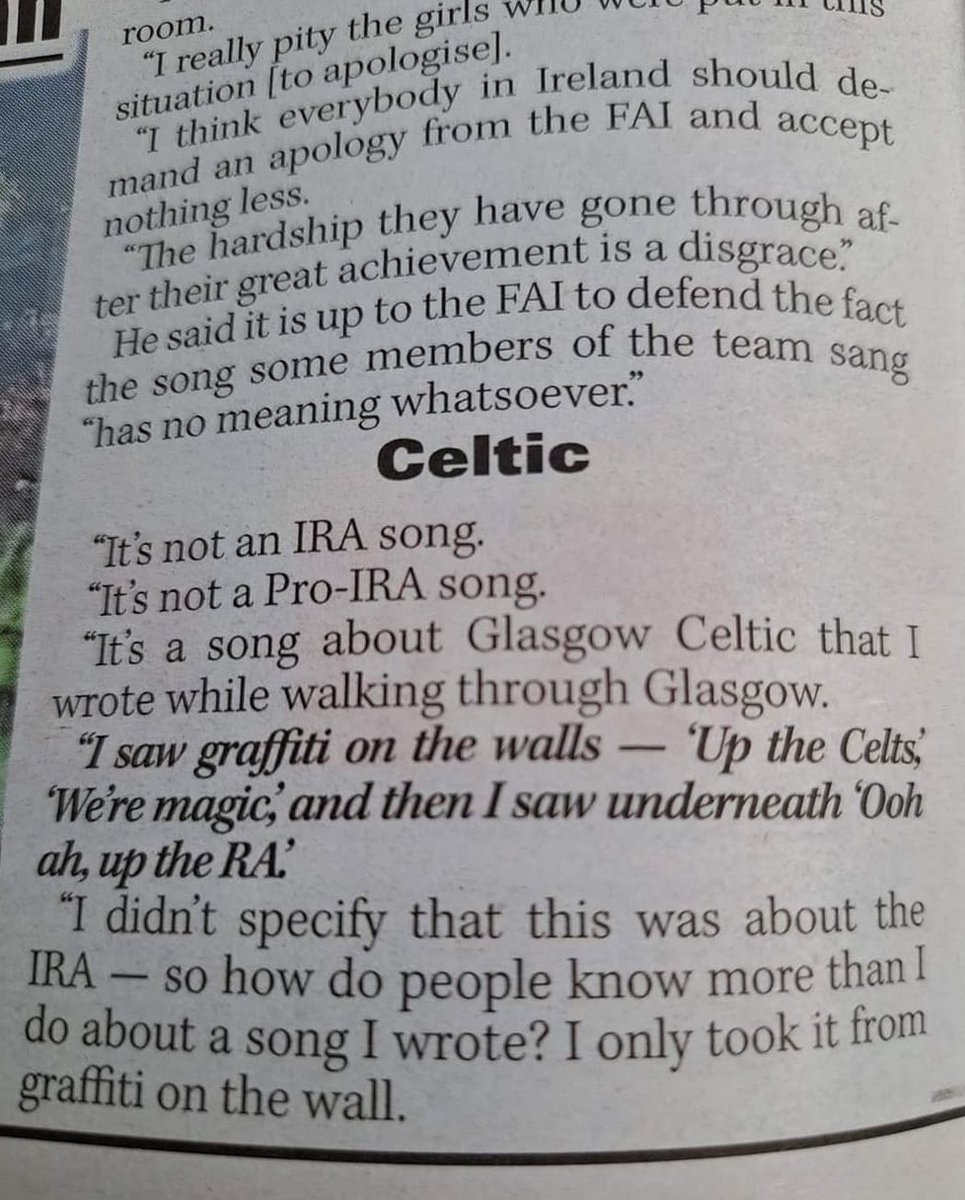

Wolfe Tones songwriter Brian Warfield has accused those who criticise his song Celtic Symphony of being “cranks and unionists or people who side with them” amid controversy over the Irish women’s football team singing along to it.

Warfield wrote the song, which includes the refrain ‘ooh, aah up the ‘Ra’, in 1987 for the centenary of Celtic Football Club, which occurred a year later.

He claims the line was taken from graffiti he saw on a wall in Glasgow around that time, which read ‘we’re magic, up the Celts, ooh, aah up the Ra’. He said he was not necessarily referring to the Provisional IRA in the lyrics.

No excuses

Celtic Symphony was playing in the dressing room while the Irish team celebrated qualifying for the World Cup after winning at Hampden Park on Tuesday night. Players were filmed singing ‘ooh, aah up the Ra’ and a clip was posted on social media.

Up the ‘Ra: The chant that does not seem to go away

Up the ‘Ra: The chant that does not seem to go away

Ireland manager Vera Pauw said she was not in the dressing-room at the time, but that there were no excuses for the actions of the players.

“From the bottom of our heart, we are so sorry because there is no excuse for hurting people. It was unnecessary,” she said. “I have spoken already with several players about it and the one who posted it is devastated, she is crying in her room. She is so, so sorry. But there is no excuse for it.”

Warfield said the women involved were being “persecuted and bullied for a song they like”.

“What the hell is wrong with IRA? It is the Irish Republican Army. It is the people who put us here and gave us some hope when we had no hope.”

Parachute Regiment

Warfield said critics of the song had no problem with God Save the King even though it now honours King Charles III, who was the honorary colonel of the Parachute Regiment which shot dead 13 civilians on Bloody Sunday in Derry in 1972.

“There were terrible things that happened on both sides, but don’t give me the argument that it was one sided. Don’t tell that you can’t sing Celtic Symphony but you can sing God Save the King? Don’t give the argument that Land of Hope and Glory isn’t a rebel song. It is.

“In England they wear poppies and rise them up to sir this and sir that for killing for English expansionism but to kill to gain Ireland’s freedom is a terrible crime.”

Warfield said he had a family reason for being opposed to British militarism. He said three of his great-uncles died in the first World War – his grandfather’s brothers Henry and George Warfield and their sister’s husband John Misseu, who was Irish of Huguenot extraction. At the time of the first World War the Warfields were a Protestant family who later converted to Catholicism.

Republic of Ireland Women: FAI issue apology for offensive song sang in dressing room after Scotland victory

The Football Association of Ireland (FAI) has issued an apology after a video was shared on social media of the Women’s National Team signing an offensive song following their World Cup win over Scotland on Tuesday.

By Graham Falk

https://www.scotsman.com/sport/football/international/republic-of-ireland-women-fai-issue-apology-for-offensive-song-sang-in-dressing-room-after-scotland-victory-3876867

A number of players posted the team’s celebration on social media as the Ireland Women’s side wildly celebrated their 1-0 victory over Scotland at Hampden Park last night – a result which means they qualify for the World Cup for the first time in their history.

The crunch game between Scotland and Republic of Ireland was decided by a single goal from striker Amber Barrett in the 72nd minute and condemned Pedro Martinez-Losa’s side to an exit from the World Cup play offs.

However, one particular video which circulated on social media appeared to show the team in the dressing room singing “Ooh ah, up the ‘RA” via an Instagram live post – a song associated with support of the Irish Republican Army.

Several social media users condemned the song in the video and now the Football Association of Ireland (FAI), and their manager Vera Pauw, have apologised in a statement released this morning.

The statement read: “The Football Association of Ireland and the Republic of Ireland Ireland Women’s National Team Manager Vera Pauw apologise for any offence caused by a song sung by players in the Ireland dressing room after the FIFA Women’s World Cup Qualifying Play-off win over Scotland at Hampden Park on Tuesday night,” the statement read.

“We apologise from the bottom of our hearts to anyone who has been offended by the content of the post-match celebrations after we had just qualified for the World Cup.

“We will review this with the players and remind them of their responsibilities in this regard. I have spoken with players this morning and we are sorry collectively for any hurt caused, there can be no excuse for that.”

ScotlandHampden ParkInstagram

Una Mullally: What does it mean to say ‘up the ’Ra’? And why does it keep happening?

https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/2022/10/13/una-mullally-what-does-it-mean-to-say-up-the-ra-and-why-does-it-keep-happening/

The women’s soccer team knew what they were doing: it’s just that what they’re doing means something different now

Expand

The Ireland squad celebrates qualifying for the World Cup. Photograph: INPHO/FAI Pool Pictures

Una Mullally’s face

Una Mullally

Thu Oct 13 2022 – 12:16

As the heroes of Irish soccer, the women’s football team, danced in their dressing room, they played the Wolfe Tones’ song, Celtic Symphony, which contains the line, “Ooh ah up the ’Ra”, and they sang along. They then had to apologise for this, and be patronised by a British broadcaster on Sky, who wondered whether there is an issue with education in the team when it comes to Irish history, a ridiculous thing for someone in British media to say, given that nation’s epic blind spots regarding its own history.

There is a question about whether it’s objectively offensive to chant “up the ’Ra”, and the answer is pretty obvious: yes it is. It is offensive to victims of the Troubles-era IRA. But the broader question is, why does a context exist in which it is not just still chanted, but in fact becoming more common?

[ ‘It shouldn’t have happened’ – Vera Pauw apologises for players’ IRA chant]

There’s another question, too, about diversity of thought in our social bubbles. I personally exist in a context where I sometimes hear “up the ’Ra” and “tiocfaidh ár lá” socially, often jokingly, but often as an umbrella toast to republicanism. But clearly many other people don’t. I also exist in a social context where many people I know abhor such rhetoric. I don’t say “up the ’Ra”, because I think it diminishes and collapses complex things into an edgy soundbite. I think it is offensive to victims of the Troubles-era IRA. By the same token, I think anti-Irish songs are also appalling, and I find English football fans singing “Rule Britannia” offensive.

What a lot of the media and the political establishment doesn’t understand is how dominant Irish pride, patriotism and indeed republicanism is as a backdrop to new generations in their thinking, identity and in their popular culture

Republic of Ireland players celebrate following victory over Scotland at Hampden Park. Photograph: Andrew Milligan/PA

The evolution of contemporary rhetoric, terminology, and discourse is driven by youth culture. But in Ireland, we have a situation where younger people are reclaiming and reinventing republican sloganeering and are then admonished by many within older generations, which is a weird exercise in political correctness in reverse.

READ MORE

In fairness, saying “I don’t mean to endorse the IRA by chanting ‘Up the ’Ra’,” is the same sort of thin defence as, “I don’t mean to be homophobic by calling something ‘gay’.” You kind of have to own it if you’re going to say it. The scary thing for older generations is that a lot of younger Irish people do actually own it. Maybe because they didn’t live through it. But maybe it’s also because an incredible amount of young Irish people identify as republican. Look at the polls in political party support. It’s right there.

[ Irish team being ‘persecuted and bullied’ for singing ‘ooh ah up the ‘Ra’, songwriter says ]

Often, our own interpretations and disassociations regarding slogans may be honestly innocent and throwaway, but that’s not how they’re received, and it’s certainly not how similar utterances were previously contextualised. But contexts change. Younger generations are aware of the older generations’ squeamishness regarding republicanism, and this in turn consolidates their gravitation towards republicanism, because it allows for something every generation wants: a differentiating factor between generations that evokes defiance.

Terms like “pearl-clutching” are thrown around to diminish the concerns of the older generation. That’s unfair, probably, but the shocked-and-appalled reactions to cultural realities are also tedious to many young people. Additionally, the context that has been created for Irish republicanism to be culturally connected to new generations is also to do with how many of the tropes that previously made Irish republicanism unfashionable, and which many in older generations still think of when it comes to republicanism — macho culture, violence, sectarianism, Catholic fundamentalism — have been dismantled.

[ Up the ‘Ra: The chant that does not seem to go away ]

Alongside all of this, one of the unspoken generational shifts that has occurred in Ireland is the lack of deference young Irish people have towards Britain. This has to do with an Irish pride that is rooted in confidence, not fear, or shame, or feelings of inadequacy created through comparison. The balance of comparisons between both countries has changed: why would someone in Ireland be envious of someone in Britain right now? Ireland is no longer backward, and Britain is going backwards.

It is a fact that anti-Britishness is increasingly acceptable socially in Ireland, but that also has a context. It’s about disliking the British state and establishment — not British people. The British political establishment hasn’t been doing itself any favours in recent years. Simultaneously, a re-examination of British colonialism across the water has been driven by young people there, and this British discourse is also available to younger people in Ireland.

It is incredibly patronising to say young people in Ireland don’t understand their history or the past. If anything, these new generations are profoundly engaged with the past

Younger generations are embarking upon a decontextualisation of republicanism that is messy, complex, and to some, wrong-headed and shocking. But it is happening because we are living in a culture where Irish republicanism is ascendant. Paulie Doyle’s 2019 piece for Vice, in which he examined the viral nature of Irish republican slogans as memes, and his 2017 piece on Gerry Adams as a meme, are well worth a read or reread for those who are out of touch with this culture.

What a lot of the media and the political establishment doesn’t understand is how dominant Irish pride, patriotism and indeed republicanism is as a backdrop to new generations in their thinking, identity and in their popular culture. For the media, the absence of clarity on this issue is due to a generation gap and a conservatism in the commentariat that often sits in a pro-status-quo anti-republicanism, filtered through an anti-Sinn Féin bias.

Fianna Fáil calls itself a republican party, but the dominance of Sinn Féin has usurped its republicanism. A couple of years ago, I heard from a middle-class first-time voter that to be politically engaged in Ireland among his peers in their late teens was to be a Sinn Féin supporter. I think many journalists, for example, think that Sinn Féin has loads of support despite their republicanism, and in spite of their primary policy being Irish unity. I understand why this mental gymnastics is happening, because it would be overwhelming for many people to actually contend with the reality that Sinn Féin’s overt republicanism is part of their popularity.

Contemporary Irish nationalism is complex, but it does dovetail with an optimistic, forward-looking pride. This pride has emerged not from an oppressive context, but from a context that has opened up, where new generations have attempted to peel away oppressive forces — primarily Irish theocracy and social conservatism — and create instead a context of equality, the central tenet of republicanism anywhere.

This pride, I believe, is nonsectarian, and yet the framework of national pride that we have to work with historically was sectarian, was anti-English, and did orientate around republicanism and concepts of Irish “freedom”. It is inevitable that as this pride morphs and evolves and is distanced from the past, things will become distorted, twisted, and there will be weird outcomes, such as a group of young women footballers in a dressing room with a Spotify playlist that’s just as likely to contain the Wolfe Tones as it is Taylor Swift. It’s worth mentioning that “Up the ‘Ra” is not a new slogan to Irish soccer. Indeed, one of the most famous Irish player chants, celebrating Paul McGrath, emerged from it.

The idea that young Irish people don’t know their history is ridiculous. Yes, of course, time passes. The memories of the Troubles are not live for new generations. How could they be? That can be incredibly difficult to take for people who lived through that time, suffered during it, were victims of it, and lost loved ones to IRA violence. It requires reminding that IRA violence — as abhorrent as it was, had a context. That’s not a defence, but it is a reason.

It also requires reminding that the IRA wasn’t the only entity maiming and killing people. There is a strange, even hurtful positivity in the contemporary context. Republican slogans and memes and chants being said, sung and shared by post-Belfast Agreement generations, demonstrate the bittersweet evidence of the absence of frequent sectarian violence on this island, that the potency of these slogans has been lost because the violence has waned.

There remains a disconnect between North and South. There is a frivolity to republican sloganeering in the South that does not exist in the North. Go figure. This is perhaps yet more evidence of southern ignorance in relation to the North. How odd to see this ignorance reborn as republicanism — the very thing the nationalist community in the North failed to see evidence of from the South in terms of connection or solidarity for decades. What a strange journey for southern apathy to take.

Questions of Irish identity abound today, and the political establishment does not answer them. If the old forces of authority — the Catholic Church, the Fianna Fáil-Fine Gael binary — have had their grip loosened, then what do we cling on to now, when those old forces of control floundered in framing identity and direction, and are therefore deemed irrelevant?

Yet it was the State that instigated something that contributed to the rise of new republicanism. The success and impact of the cultural activity and national discourse in 2016 regarding the 1916 centenary is still in the air. You cannot spend a year talking about our patriot dead, the great heroes of republicanism, offering new insights — particularly feminist framings — of revolution, literally have military parades in the Irish capital, display iconography everywhere, create multiple new avenues into this history, make it accessible, talk big ideas, and then expect people not to engage with republicanism.

It is incredibly patronising to say young people in Ireland don’t understand their history or the past. If anything, these new generations are profoundly engaged with the past (and with the future) because they have been made reassess and reimagine in ways previous generations could not, such was those generations’ experiences of oppression and indoctrination.

We are witnessing a profound cultural shift in this country that has emerged from a confluence of factors underpinned by generational change, one that is under-recognised and misunderstood. Patronising young people for their engagement with republicanism — through meme, song, philosophy, history, messy reinterpretations, culture, frivolousness, seriousness or otherwise — is wrong-headed and out of touch.

I don’t believe the women’s football team was thinking deeply about what they were singing. But that’s the thing, isn’t it? Not digging deep doesn’t mean the articulation is shallow. When something is in the culture, it’s right there on the surface, and it pops up. Yes, “Up the ‘Ra” is offensive to many people. Yes, it is chanted by many people. Yes, it is shocking to many people. Yes, it is familiar to many people. Assuming “they don’t know what they’re doing” is wrong. They do know what they’re doing, it’s just that what they’re doing means something different now.

Unless those appalled by that begin to understand the contemporary context, how Irish culture is moving, and where the politics impacted by that culture is going, they will feel even more discombobulated as Irish republicanism and Irish nationalism grow.

Irish Times/Ipsos poll indicates most people do not believe ‘Up the Ra’ chants glorify IRA

https://www.irishtimes.com/politics/2022/10/29/irish-timesipsos-poll-indicates-up-the-ra-chants-do-not-glorify-ira/

Respondents questioned about controversial after-match celebrations by victorious Republic of Ireland women’s football team

Republic of Ireland players celebrate following victory over Scotland at Hampden Park. The players were later filmed singing the pro-IRA song Celtic Symphony. File photograph: PA

Pat Leahy

Sat Oct 29 2022 – 05:00

A clear majority of voters say that people who sing songs which contain pro-IRA chants do not “mean to glorify the IRA”, the latest Irish Times/Ipsos opinion poll finds.

Respondents to the poll were asked about the controversy that arose recently when the Irish women’s football team were filmed singing the song Celtic Symphony which included the chant “ooh ahh up the ‘Ra” — a reference to the Provisional IRA. The team and their manager apologised following criticism after the footage circulated on social media.

Respondents were asked which in a series of statements about the subject came closest to their views on the issue. A large majority of those who expressed an opinion (59 per cent) said they “don’t think people mean to glorify the IRA by singing these songs”.

This was the most common view across all age ranges, social classes and regions, but was strongest in Munster (66 per cent), among those aged 18-24 (63 per cent) and the wealthiest ABC1 voters (63 per cent).

Just over a fifth of voters (22 per cent) agreed that “people shouldn’t sing songs with IRA chants as they are offensive to IRA victims”; a view that was most popular among older voters, with 36 per cent of those over age 65 agreeing. Just 11 per cent of the youngest 18-24 voters agreed.

Poll: Support for Ukraine strong but accommodation worries mount

Listen | 00:00

Just 12 per cent of voters said that they think “it’s okay to sing songs in praise of the Provisional IRA”. Seven per cent said that they had no opinion.

ADVERTISEMENT

Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael voters are most likely to think that people should not sing these songs. Among Sinn Féin voters, just 13 per cent of respondents say that people shouldn’t sing them, while almost one in five (19 per cent) say that it’s okay to sing songs in praise of the Provisional IRA. Almost two-thirds of Sinn Féin voters say that people don’t mean to glorify the IRA by singing them.

[ Fintan O’Toole: The full, unexpurgated version of Up the ’Ra ]

[ Una Mullally: What does it mean to say ‘up the ’Ra’? And why does it keep happening? ]

The poll was conducted among 1,200 adults at 120 sampling points across all constituencies between October 23rd-25th. Respondents were interviewed at their own homes. And the accuracy is estimated at plus or minus 2.8 per cent.

Séamas O’Reilly: ‘Celtic Symphony’ detractors could do with thinking harder about their outrage

Brian Warfield, Noel Nagle and Tommy Byrne of The Wolfe Tones perform at Electric Picnic Festival 2023 at Stradbally Estate on September 03, 2023, in Stradbally, Ireland. Pic: Debbie Hickey/Getty Images

This time it’s the record-breaking turnout for the band at Electric Picnic, but last Autumn it was the Irish Women’s Football squad, who sang the band’s 1987 song ‘Celtic Symphony’ in the team dressing room, unleashing a din of condemnation that almost overshadowed their achievement in qualifying for their first ever world cup.