| Willie Maley Homepage |

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Entry

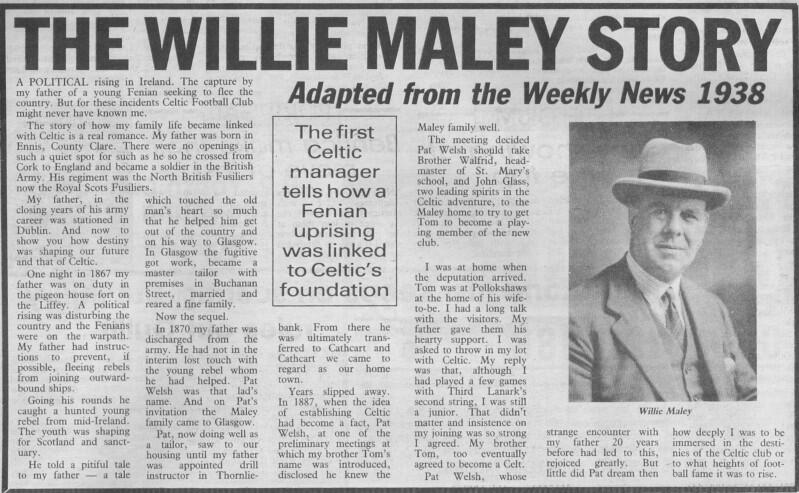

Maley, William [Willie] (1868–1958),football manager and businessman, was born at the barracks, Newry, co. Down, on 25 April 1868, the third of six sons of Thomas Maley, a sergeant instructor with the North British fusiliers, and his wife, Mary, née Montgomery. He spent most of his childhood near Cathcart, Renfrewshire, but left school in 1881, aged thirteen, and entered an office in Glasgow with the aim of becoming a chartered accountant.

In 1888 Maley began his long association with Glasgow Celtic Football Club. The club had been formed earlier that year to provide a social focus for the large number of Irish immigrants flocking to the city and to raise money from the proceeds of matches to relieve poverty among the Catholic Irish community in the east end of Glasgow. The club began recruiting players, and Maley’s elder brother Tom caught their eye, but Willie happened to be at home when the club’s representative called and he was invited to join. A wing-half, he proved good enough to be a club regular for five years, and was selected to represent Scotland against both Ireland and England in 1893, but he played poorly in the latter fixture and was never chosen for his country again. By 1896, when Celtic was in the process of conversion to a limited company, he had decided to confine himself to football administration, and in 1897 he became the club’s secretary–manager, a post he was to fill for the next forty-four years.

Maley was arguably the first football manager in the modern understanding of the term, and guided Celtic to become the leading Scottish club in the early twentieth century, winning the league championship in six consecutive seasons from 1905 to 1910. Some of his influence was captured by a newspaper comment: ‘He catches the players young and breathes into them the old traditional Celtic fire of which he himself appears to be the very living fountain and source’ (Glasgow Observer, 14 March 1914).

Like his predecessor J. H. McLaughlin, the first Celtic secretary, he was a stout exponent of professionalism. ‘Shamateurism’, he argued, enabled players to ‘debauch themselves without being called to account’ whereas open professionalism ensured that clubs could be masters of their players. He also took a wider view of the game’s development, encouraging its spread beyond Britain by taking Celtic on exhibition trips to Europe, and especially the Austro-Hungarian empire, where the club played a number of fixtures before 1914.

After the First World War, Celtic lost something of their earlier dominance with the emergence of an ambitious Rangers side under Maley’s friend and rival William Struth. Rangers became the dominant league side, but Celtic won the Scottish cup six times in the inter-war years and were popular visitors to the United States. In a period of intense religious sectarianism between the two Glasgow clubs, Maley was always resistant to the notion that Celtic should employ only Catholic players. Apart from his personal repugnance to the policy of sectarianism, he probably realized the disadvantage of confining his recruitment to the smaller community: ecumenism meant that he could sign a protestant and deprive Rangers of a player.

At least five of the 1938 Celtic side which won the Scottish cup and league championship were nominal protestants. In that year Maley’s fifty years with Celtic were marked by the presentation of a purse containing 200 guineas, and in 1939 he wrote a lively but partisan history of the club,The Story of Celtic. In February 1940, however, when the club not unreasonably felt that the time had come for a change in management, Maley took it badly and the parting was bitter. He avoided Celtic Park for a decade, and a reconciliation was effected only shortly before his death.

Maley’s overriding characteristic was efficiency, which he combined with a brusqueness of manner which could be, and perhaps was designed to be, upsetting. He also possessed considerable financial acumen: he acquired a sports outfitter’s shop at the age of twenty-six, and subsequently owned a thriving restaurant in the centre of Glasgow. He was also the prime mover in attracting the world cycling championships to Scotland and was president of the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association. He was also president of the Scottish Football League from 1921 until 1924, when club managers were debarred from the position. Willie Maley died in Glasgow on 2 April 1958. A requiem mass was said at St Peter’s Church, Partick.

Robert A. Crampsey

Sources

T. Campbell and P. Woods,The glory and the dream: the history of Celtic F.C., 1887–1986(1986) · B. Murray,The old firm(1984) · R. A. Crampsey,The Scottish Football League: the first 100 years(1990) ·(1958)Likenesses: photograph, repro. in A. Gibson and W. Pickford,Association Football and the men who made it, 3 [1906], facing p. 192Wealth at death: £11,404 6s. 10d.: confirmation, 29 May 1958.

Robert A. Crampsey, ‘Maley, William [Willie](1868–1958)’,Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/57834, accessed28 June 2011]William Maley (1868–1958): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/57834

Willie Maley & Athletics

Willie Maley and Celtic were synonymous – after two spells there as a player he was their

secretary – manager from 1897 – 1940. His a football career is well documented but we quote

here fro his chapter in “Fifty Years of Athletics” published by the SAAA in 1933.

“Tell how I got mixed up in athletics? A short story. We lads in Cathcart village used up all

our spare tie in athletics. My strong suits were football, quoiting and running. One of the

chiefs in my office further advanced me. He was a big noise in the Clydesdale Harriers –

Andrew Dick. My all round abilities convinced him that I was a suitable subject for his club

which had fast been gaining fame for the number of its activities. I

found myself among the starters in a Junior cross country race. I enjoyed the novelty and was

rather pleased in being placed. Despite the fact that I touched wood and issued the water! I

was soon able to walk normally.

To the track was the next command. On the Abercorn Ground, Paisley, I appeared with other

sprinters and carried off the prize. Pot-hunting I always abhorred, so I confined myself to the

odd prizes here and there. I kept on doing that sort of thing until one breezy afternoon I varied

things by winning the 100 yards championship (SAAU). As I had been pushed into it, so I

pushed my brother To, and right well he responded. He made his debut at the Queen’s Park

Sports and collared the Open 100. That is how we celebrated the Jubilee year. Celtic, the new

football club, absorbed me and my time ever since.”

Not entirely – even after becoming Celtic manager he promoted many Sports Meetings from

the Westmarch Ground (then the St Mirren FC ground) to Celtic Park in Glasgow. As a runner

he had been an excellent sprinter over 100, 220 and 440 yards. He won the SAAU 100 yards

title in June 1896 at Hampden Park in 11 seconds dead having effectively retired from running

to concentrate on football. A natural athlete a contemporary described him thus: “Did you see

Maley? He ran like a deer, dodged like a squirrel and shot like a catapult.”

Willie Maley’s one and only League game for City – Loughborough Town (Home) 24.2.1896.

City won 5-1 at Hyde Road.

Mr. Willie Maley, Celtic F.C.

October 24, 1904 kjehan Other clubs news, Player news Leave a comment

October 24, 1904

Being English by birth Mr. William Maley has the suavity of that race, a Scot by adoption, he has the caution proverbial of that nationality, and an Irishman by association and sympathy, he has the fiery enthusiasm of the true Hibernian – all constituting a combination of qualities admirably suited for the profession he has chosen to follow.

The son of an army instructor, who was widely respected in Glasgow volunteer circles, Mr. Maley has inherited to some extent the discipline of the father, and this be exercises with a stern will, and applies relentlessly when his team has a cup-tie or an important League engagement to face.

Having been an athlete himself. Mr. Maley knows the value of systematic training, and insists upon every member of the team doing so much exercise every day. A half-back of no mean order, Mr. Maley did good service to the Celtic in the opening years of its history, and he can show more than one representative honour.

He had a great ambition to figure in an international match, just as every player has. It was much difficult to get “caps” in Maley’s day than it is now, as the players then were of a higher grade than the players now while the methods of selection were less susceptible to outside influence. In 1893 Mr. Maley played against England and Ireland, and though Scotland were defeated by our friends across the border on that occasion, the Celtic half was by no means a failure.

Possessed of great speed, Mr. Maley was an excellent “recover,” and, generally speaking, he was a sound all-round player. Before the Celtic Club was formed he played for Third Lanark and Partick Thistle, and it was while a member of the latter that he scored several successes on the pedestrian track, though in this department of sport he was scarcely so versatile as his brother Tom, who is now associated with the management of the Manchester City Club.

Mr. Maley is great as an athletic organizer, and has more than once been a committee member of the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association, in which he might have occupied high office long ere this had he been in a position to devote more time to its work. The Celtic carnivals have a world-wide fame. Getting a free hand, he makes the most of it, with the result that there is scarcely an athlete of note who has not, in the heyday of his greatness, been the guest of the Celtic club.

Mr. Maley, in fact, prides himself on his athletic carnivals, and there is only one other gentleman in Scotland who claims to have done so much, if not more, for athletics, and that is his warm friend, Mr. Gavin Stevenson, of Ayr. Personally, I am inclined to divide honours equally between these two gentlemen, and neither the one nor the other should feel it derogatory to be coupled together in a cause so interesting.

Mr. Maley has the undivided confidence of his directors, among whom are several of the most astute gentlemen connected with Scottish football. He is, therefore, well fortified in the matter of advice, and by relying on those above him. Mr. Maley rarely finds himself in a position compromising to himself or the Celtic club.

Trained, too, in one of the first legal firms in Glasgow, Mr. Maley may be said to have been schooled in secretarial procedure, while his insight into law, with all its intricacies, has more than once enabled him to keep clear of litigation.

In private, Mr. Maley is a delightful conversationalist, and he has a store of anecdotes connected with football and athletics which, were he to give to the public, would be as entertaining as it would be sensational. Scottish official life would be dull without Mr. Maley.

(Source: Athletic News: October 24, 1904)

If Brendan Rodgers’ dominant Celtic set a new record they deserve to be fully acclaimed as ‘The History Bhoys’

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-5048639/Brendan-Rodgers-Celtic-deserve-fully-acclaimed.html

By John Mcgarry For The Scottish Daily Mail

Published: 23:49, 3 November 2017 | Updated: 23:49, 3 November 2017

As Celtic descend upon McDiarmid Park at lunchtime on Saturday, the scent of history in their nostrils owes much to the intervention of central government over a century ago.

As the First World War broke out in the summer of 1914, it was decreed that organised sport would not just continue but be actively encouraged due to the benefit to fitness and morale.

Had Herbert Asquith, the Liberal prime minister of the day, taken an opposing view, Willie Maley’s all-conquering side would have been denied the opportunity to string together 62 domestic games without loss between November 1915 and April 1917.

Brendan Rodgers is 90 minutes away from breaking the British record for unbeaten games

+3

Brendan Rodgers is 90 minutes away from breaking the British record for unbeaten games

Accordingly, the British record – which could be surpassed on Saturday afternoon – would never have been set.

If Brendan Rodgers’ side do go one game better, there is no question they will have earned every plaudit going.

Because by any stretch of the imagination, the side assembled by the legendary Maley in that period stands comparison with any in the club’s history.

Containing the likes of Patsy Gallacher, Jimmy ‘Napoleon’ McMenemy and ‘The Mighty’ Jimmy Quinn, they were without question the pre-eminent force in the land.

They won four straight titles between 1913 and 1917 and would almost certainly have achieved more had the outbreak of the Great War not restricted the silverware on offer.

‘It was a very good side,’ explained Celtic historian David Potter. ‘Before the war started in 1914, they’d won the league and cup double and were reckoned to be one of the best sides around that time.

‘And during the war, they more or less won everything else. Gallacher, McMenemy and Quinn would sit alongside Jimmy Johnstone and Henrik Larsson in the pantheon of the all-time greats. No question.’

For the paying public, the sight of such stars still playing for the club each Saturday was a welcome distraction from a war most believed would be over by the first Christmas but for which there was soon to be no end in sight.

The game was not impervious to what was going on in the wider world, though. On government orders, matches were restricted to Saturdays and public holidays.

Willie Maley’s all-conquering Celtic went 62 domestic games unbeaten between 1915 and 1917

The Scottish FA began the qualifying rounds of the Scottish Cup in 1914 but abandoned the competition at the turn of the year as crowds plummeted. The old second division was suspended with two regional leagues put in its place.

With supplies of fuel and lighting curtailed, the league rejected a proposal to cut the duration of games back to 80 minutes during December and January.

In June 1917, the league’s three most outlying clubs, Aberdeen, Dundee and Raith Rovers, agreed to temporarily stand down in order to alleviate travel concerns and didn’t return until two years later.

The most obvious threat to any side’s hopes of success in that era, of course, was men answering the call.

Thirteen players signed to Celtic went off to battle throughout the war’s duration. Peter Johnstone, a defender who won three Scottish Cups and four championships, was killed at the Battle of Arras in 1917.

‘With all our regulars and a few new recruits to bring along, our prospects for 1914/15 were bright indeed,’ Maley wrote.

‘But as the season was on the point of beginning, the drums of war resounded throughout the land. A number of lads answered the call immediately although no one realised that it was going to last so long and as time went on our ranks were depleted gradually.’

Those players who remained were not sheltered from the reality of the world. Their wages were reduced from £4 to £1 a week. Rationing wasn’t introduced until 1918 but as the war progressed, fresh fruit, vegetables and meat got harder to come by.

The winter of 1916 saw a major shortage of flour. Government posters encouraged people to eat less bread. The alternative was using dried, ground-up turnips which produced an unappetising, diarrhoea-inducing equivalent. Hardly ideal for athletes.

Born to a British Army sergeant in barracks in Newry, County Down, Maley was keen that Celtic did all they could to help the war effort.

Announcements asking for recruits were made over the loudspeaker at Celtic Park at half-time. On one occasion an exhibition of trench warfare was held there.

Rodgers’ side will deserve every plaudit going if they break the long-standing record

+3

Rodgers’ side will deserve every plaudit going if they break the long-standing record

‘That happened at a lot of grounds,’ Potter explained. ‘They were places where young men would gather so it was fertile ground for recruiting. Maley encouraged that because his father had been a soldier.

‘But people like him were also very keen that football would continue due to the positive effect on morale.

‘Once a game had finished, he made sure the results were telegraphed to the war office. They sent it onto the trenches so the soldiers knew the score about half an hour after the full-time whistle.

‘They said that Patsy Gallacher was the most talked about man in the trenches among Scottish soldiers – more so than King George or the Kaiser.’

The man who would manage Celtic for a remarkable 43 years from 1897 believed the club could play its part in defeating the enemy without cutting the legs from beneath his side, though.

He made is his business for his star players to be taken on in ‘reserved occupations’, thereby helping the national effort while simultaneously ensuring they were not conscripted.

‘One of Willie Maley’s greatest assets was he had a wide circle of contacts,’ Potter explained.

‘He made sure all of his players got jobs that were war related so they couldn’ t be accused of war dodging. In many cases, they couldn’t be taken away from these jobs because they were so vital.

‘Andy McAtee was a miner. Patsy Gallacher worked in the shipyards. He was actually fined for bad time-keeping by the shipyards and because of that he wasn’t allowed to play for Celtic on a Saturday afternoon for eight matches.’

Such personnel issues mattered little to Maley’s men, though. Writing after the 1916 league title had been won, the manager wrote: ‘Although we were often in sore straits to field a team, the players, sometimes almost complete strangers to our regulars but proud to wear the colours with traditional enthusiasm, upheld our reputation so well that another title was won with the loss of only eight points in 38 games.’

That Celtic were deserving of that third straight title was beyond all debate. Facing a fixture backlog on account of only playing matches on Saturdays, April 15, 1916, became renowned as the day on which they would play two games.

‘They won the pair of them,’ Potter said. ‘Raith Rovers at home then Motherwell away. I think they kicked off at 3.30pm and 6.30pm. They just finished one game and jumped on a bus. In doing so they won the league championship that day.’

It would be a full year before they would taste defeat again. Kilmarnock, the side they defeated 2-0 at the outset of the run, exacted revenge by winning by the same score on April 21, 1917.

One hundred years on, a feat most thought to be unreachable might just be surpassed. In this month of remembrance, though, the achievements of a generation gone should not be overlooked.

MR WILLIAM MALEY, CELTIC F.C.

A great club is the embodiment of a great idea. The Celtic are such a club, and the subject of our sketch was one of the gentlemen who put into plain and practical shape a plan long cherished for the formation of the club. The wisdom of the originators of the Celtic is seen in the position the club occupies, although it has only been two years in existence. The marvellously rapid progress of the club is due undoubtedly to the playing power of the members who compose the team, but it is also attributable to the excellent executive which since the club’s inception has guided its efforts. Mr Maley is one of the best of these.

Too modest to shine on the field where he always seems to be holding himself in reserve, his light burns brightly in the council chamber. The Celtic, like every other club, requires advisers, and in Mr Maley it has one of the most judicious, one whose opinions are admired for their soundness, heightened by a manner of expression that commands for them increased respect. Mr Maley is not an orator, and thinks before he speaks. He looks soft and pliable, but that is only a freak of nature, for he is hard – nay, clear-headed – and does not wear eye-glasses. To people in general he is reserved to the border of indifference; among his friends and club mates he is familiar, yet dignified. Men of Mr Maley’s stamp are a distinct gain to the intellectual side of a physical pastime which is bound by profit by the connection. He was not born with a proverbial silver spoon in his mouth, but he is a gentleman, because he could be nothing else. Our estimate of his character is thus summed up – mild, mannered, manly Maley.

[Scottish Referee 25 August 1890]