H | Player Pics | A-Z of players

Biog

Fullname: Gilbert Saint Elmo Heron

aka: Gilbert Heron, Gillie, the “Black Arrow”, the “Black Flash”, Gil Heron, Giles Heron

Born: 9 Apr 1922

Died: 27 Nov 2008

Birthplace: Kingston, Jamaica

Signed: 4 Aug 1951 (from Detroit Corinthians)

Left: 17 May 1952 (free); Third Lanark (1 July 1952)

Position: Centre-forward

Debut: Celtic 2-0 Morton, Aug 18 1951, League cup

Internationals: Jamaica

Trivia

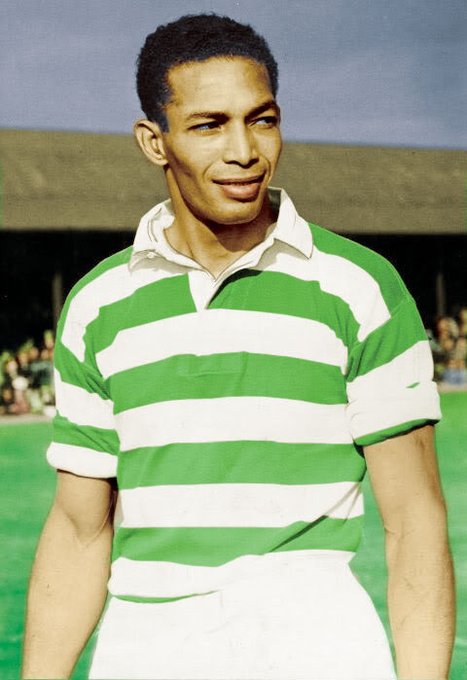

- The first black footballer to play for Celtic for the first team in a competitive match.

- Prior to Gil Heron, the first non-white player in the Celtic squad was Mohammed Salim who was Indian but Mohammed Salim did not end up playing for the first team but only for the reserves.

- First black professional footballer in Scotland in the 20th century, previous black footballers in the early days (e.g. Andrew Watson) were technically amateurs. Although John Walker (mixed race) of Hearts from the 19th century is believed to be the first professional black footballer in the Scottish leagues.

- Father of Gil Scott Heron, legendary American musician famous for his work in pioneering Jazz, soul, rap and other African American styles of music in the sixties, his most famous composition being the seminal “The Revolution will not be televised“. Gil Scott-Heron is commonly referred to as the “Godfather of Hip Hop“.

- Gil Heron’s last game was the one before Jock Stein’s debut for Celtic. If they’d played together, maybe things could have been very different for him.

- Gil Heron’s son (Gil Scott-Heron) said that through his life after leaving he’d always still check for the Celtic scores.

- Robert King one of the feted Angola Three became a Celtic fan, it is believed possibly via the influence of Gil Scott-Heron (see link).

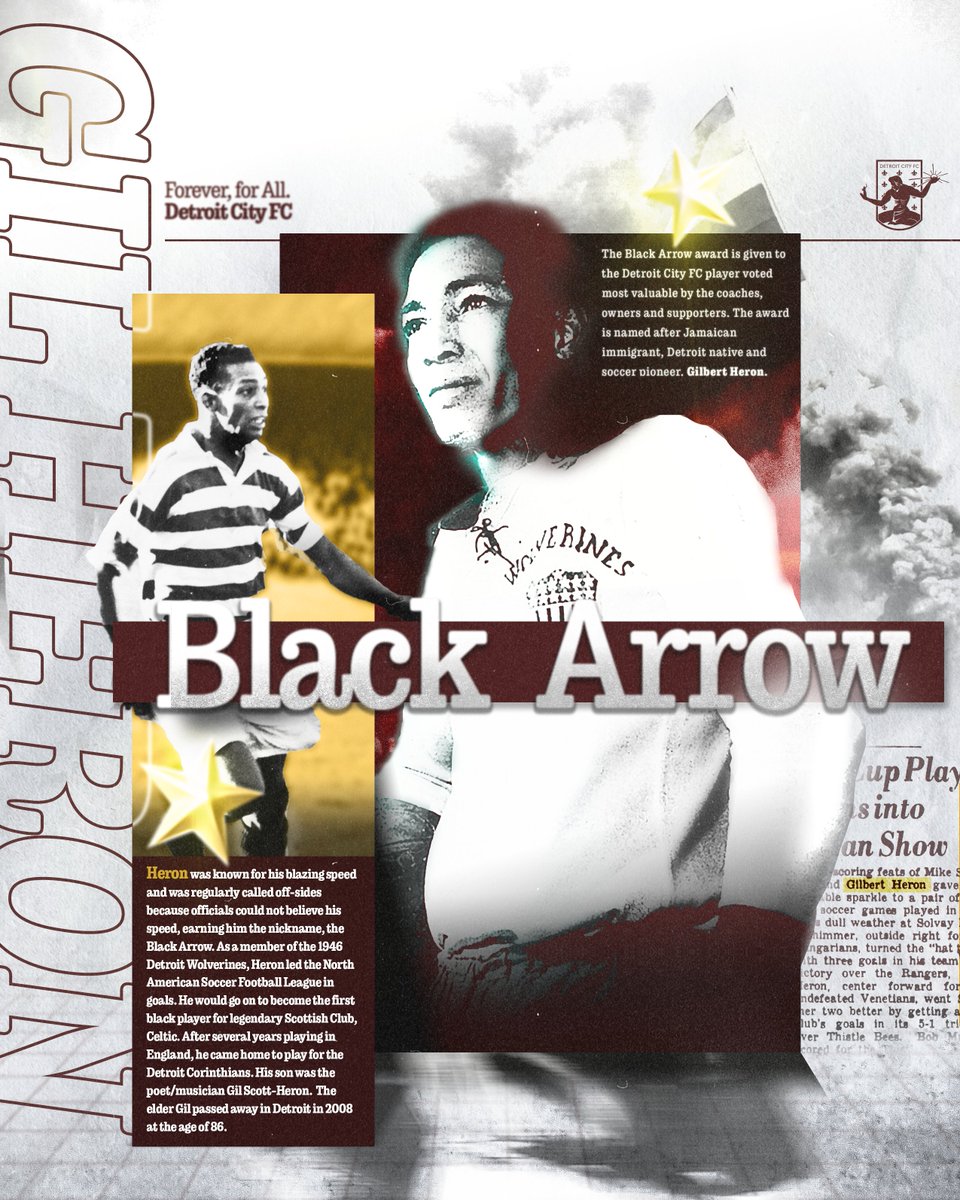

- @DetroitCityFC: “Every year, players, coaches, and fans come together to vote for the season’s Black Arrow. The award is named after soccer legend Gil Heron, the first Black player to play for Scottish team Celtic FC. Read more about him and his connection to Detroit below.“

Biog

| “There are no greater bunch of boys than those at the paradise [Celtic Park].” Gil Heron |

One of the first black players to play in Britain, Gil Heron became the first Afro-Caribbean player to play first team football for Celtic.

Born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1922, Gil Heron played as centre forward for the Jamaican national team as well as playing for the American club side Detroit Corinthians. On a North American tour he was spotted by a Celtic scout and later signed for the club in 1951.

Gil Heron scored on his début, the second goal in a 2-0 win against Morton during the 1951-52 season, and was hailed as a ‘box-office’ hit and was bestowed the nicknames of “Black Flash” and “Black Arrow“. He had a fine debut and reports were positive:

“He has ball control, magnificent headwork and can trap like a veteran… took his goal with camera-shutter speed”.

He was so quick off the mark, that he was said to be repeatedly given as offside as linesmen couldn’t credit anyone being so fast.

He was given a short run in the League Cup, which in those days was played early on in the season, and scored one further goal, the winner v Airdrie in a 1-0 victory.

At a time when Scottish football was notable for its physical nature, Gil Heron soon struggled – as one local newspaper put it: “lacking resource when challenged“. After the league cup run he was only given a single league cup match appearance, 2-1 win v Partick Thistle in December 1951, to try to prove himself. Celtic were doing poorly in the league at this time, and finished the season in ninth place far behind title winners Hibernian.

The other problem was cliques at the club. Celtic were generally poor in this era, and it was remarked that Celtic’s star player John McPhail did not like challengers to his role, and so both Gil Heron and fellow Celtic teammate Leslie Johnstone were underminded. It didn’t help matters and marked various people at the club down, including the poor team management. Other players like Bobby Collins & Sean Fallon took to Gil Heron very well.

The writer Phil Vasili noted that Gil Heron was criticised in Glasgow for “being unable to transfer his pugilistic tenacity” (Gil Heron had previously been both an athlete and a boxer). He was released barely a year later and signed for Third Lanark in May 1952; he hadn’t featured for the first team for some time so a move was a practical decision. He reportedly said on his departure:

“I may go home. I wouldn’t get the same thrill from another club”.

Despite the disappointment of his lack of success, the truth is that when you look at his record at his later clubs (i.e. Third Lanark & Kidderminster Harriers), there was a repeat pattern as at Celtic: great start then sharp fall from grace and then out the first team. He did have a great goal scoring record for Celtic reserves, but also was disciplined for an on field fight during a match v Stirling Albion reserves which will have been frowned upon by Celtic’s over-controlling chairman (Bob Kelly).

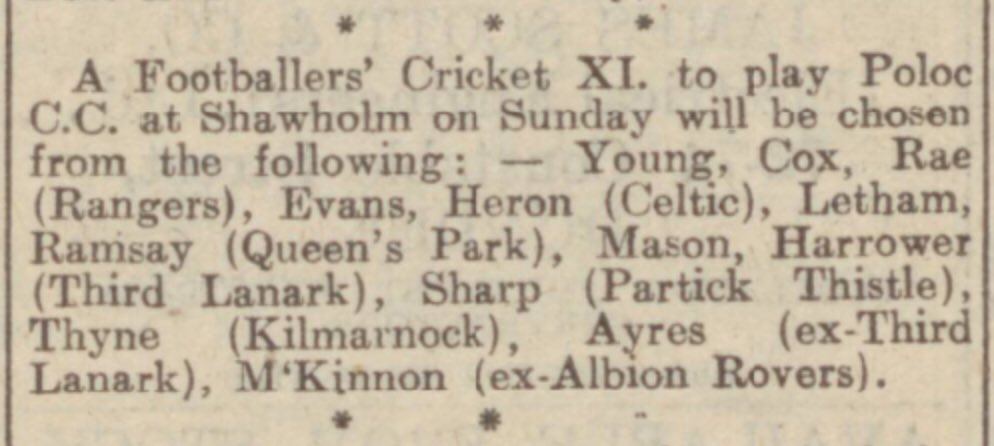

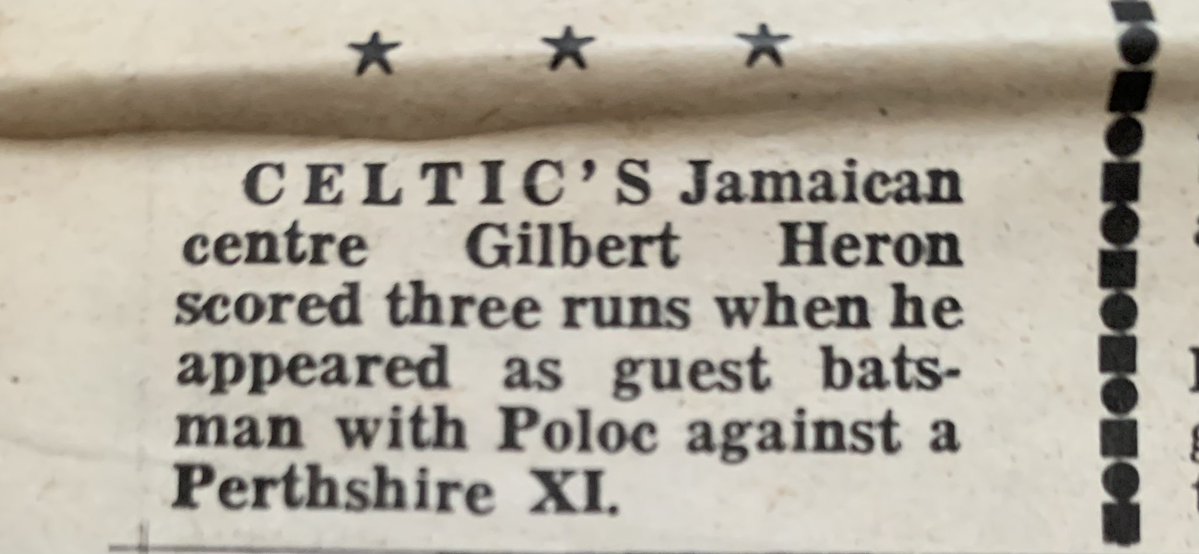

Whilst in Glasgow, he joined Polloc Cricket Club and played for them too, his record was: 14 innings in 15 matches for the Polloc first XI in season 1952. He scored 336 runs, at an average of 28.00, with a highest score of 51* – also his only half-century for the year. Not bad. In 1952, he played in a Cricket match for a ‘Footballers Select XI’ alongside fellow Celt Bobby Evans & other Scottish footballers against a Polloc CC XI.

The summer of 1953 saw him head to Paisley with his cricket bat to play for Ferguslie Cricket Club.

Gil Heron later played for Kidderminster Harriers before returning back home to the US to play for his original club, the Detroit Corinthians, where his son, the acclaimed jazz musician and poet Gil Scott-Heron, had been born in 1949. Sadly, Gil Heron and his wife had already split up on his departure to Scotland and he did not see his lauded son until he was 26. This meeting is immortalised on Gill Scott-Heron’s “Bridges” album on the opening song “Hello Sunday! Hello Road!”.

Shortly before Gil Heron’s son (Gil Scott-Heron) once visited Scotland to promote his new book “The Last Holiday“, a local journalist asked about his father’s experiences of playing football in Glasgow:

“My father still keeps up with what Celtic are doing. You Scottish folk always mention that my Dad played for Celtic, it’s a blessing from the spirits! Like that’s two things that Scottish folks love the most; music and football and they got one representative from each of those from my family!”

Despite Gil Heron’s relatively brief spell at Celtic, it is apparent that Gil Heron Sr still retained fond memories of his time in Scotland. He passed away in 2008.

It became a tradition of studious Gil Scott-Heron fans to show up at his Glasgow shows in the green and white hooped shirt of Celtic. Gil Scott-Heron joked at one concert:

“There you go again – once again overshadowed by a parent. I’m going to wear my Celtic scarf and Rangers hat when I come over!“

A good sense of humour and a firm favourite of the Celtic diaspora, sadly he has now also passed away but along with his father is much fondly remembered.

Playing Career

| APPEARANCES | LEAGUE | SCOTTISH CUP | LEAGUE CUP | EUROPE | TOTAL |

| 1951-52 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| Goals: | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Matches played

18 Aug 1951, 2-0 win v Morton (LC),

– Gil Heron’s debut before a crowd of 40,000. Scored Celtic’s second goal in 35 minutes with a shot from outside the penalty box.

25 Aug 1951, 1-0 win v Third Lanark (LC)

29 Aug 1951, 1-0 win v Airdrie (LC) (scored a goal)

1 Sep 1951, 0-1 loss v Morton (LC)

1 Dec 1951, 2-1 win v Partick Thistle (Lge)

Honours with Celtic

none

Pictures

Articles

- Article taken from a Google archive of: http://www.footballculture.net/players/int_heron.html

- Gil Heron games

- Gerry Hassan writes on Gil and his famous son

Links

Articles

Death of former Celt Gil Heron

From CelticFC.Net

Newsroom Staff

FORMER Celtic player Gil Heron has died at the age of 87. He passed away in a nursing home in Detroit on Thursday, November 27.

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, Gil had been playing in the United States and was invited to Scotland and took part in a public trial at Celtic Park on August 4, 1951, scoring twice in the game.

It was enough to impress the club who signed him and he made his debut on August 18, 1951 in a League Cup tie against Morton at Celtic Park. He scored once in a 2-0 victory.

He stayed a year at Celtic, making five appearances and scoring two goals before joining Third Lanark.

He eventually returned to the United States, settling in Detroit. He was also the father of famous jazz musician, Gil Scott-Heron.

The thoughts and prayers of everyone at Celtic are with Gil Heron’s family and friends at this sad time.

‘Black Arrow’ Gil Heron a trailblazer at Celtic – Father of famous jazz musician dies aged 87

(Scotsman)

Published Date: 02 December 2008

Published Date: 02 December 2008GIL Heron, who has died at the age of 87, was a Jamaican-born striker who enjoyed a short spell in Scottish football with Celtic and Third Lanark.

He played in the United States both before and after his stay in Scotland, and was the father of the famous jazz musician Gil Scott-Heron.

Born in Kingston in 1921, Gilbert Heron moved to Canada as a boy, and is believed to have first shown evidence of his footballing prowess during a spell in the Royal Canadian Air Force. He moved to the USA after the Second World War and joined the Detroit Wolverines. The Wolverines were founder members of the newly established North American Professional Soccer League, an organisation which had been set up by Fred Weiszmann, the owner of the Chicago Maroons club, after his application to join the American Soccer League for season 1946-47 had been turned down.

The ASL had wanted Weiszmann to found a Midwest Division of their organisation, but he decided to go his own way instead. The Wolverines were one of five teams in the league, and they were inaugural league champions in 1946 thanks largely to Heron’s goals. They were unable to retain their title the following year, after which the NAPSL folded. The striker then joined Detroit Corinthians, and it was while playing for this team that he was spotted by a Celtic scout who was on tour with the club. Invited to come over to Glasgow, he was signed after scoring twice in a trial match at Celtic Park in August 1951, and quickly acquired the nickname “the Black Arrow.”

He made his debut later that same month in a League Cup tie against Morton, and scored one of his team’s goals in a 2-0 victory. But such an auspicious start to his career did not lead to long-term success at Parkhead, and after a year he was allowed to join Third Lanark. After another short spell there he moved to Kidderminster in England, and then returned to Detroit where he played out the rest of his career with the Corinthians.

He is widely believed to have been the first black footballer to play for Celtic, but it is hard to say for sure given the lack of thorough documentation during the early decades of the professional game in Scotland. The obituary on the Celtic website, www.celticfc.net, does not claim he was. It is known for certain that there were black players at other clubs long before Heron crossed the Atlantic.

After his brief period of celebrity in the 1950s he appeared destined to fade into obscurity, but memories of him were revived in the 1970s by the growing fame of his son. Gil Scott-Heron was born in Chicago in 1949, and stayed behind in America while his father migrated temporarily to the UK. Scott-Heron’s earlier recorded compositions, the most well-known of which was “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” were forerunners of rap and hip hop in both their spoken-word delivery and political content. In the 1980s he became a fierce critic of the economic policies of President Ronald Reagan, and also supported the anti-nuclear movement.

Later, disillusioned with the direction in which many rap artists were going, he released the track “Message To The Messengers” in which he called for an end to egotistic posturing and a return to political commitment within the genre. He has served two drugs-related prison terms this decade, and has announced that he is HIV positive.

Little is known about the later years of Gil Heron. After his retirement from football he appears to have stayed on in Detroit. He died in a nursing home in the city last Thursday, 27 November.

BLACK ARROW R.I.P

Provided by: Mirror

THE first black player to appear for Celtic, Gil Heron, has died in Detroit, aged 87.

Bhoys fans paid tribute to him on club forums. One, from Tim Park, on TalkCeltic said: “Rip Mr Heron – Celtic FC bringing down barriers even then.”

Known as the Black Arrow, Jamaican-born Heron, the father of jazz legend Gil Scott-Heron, became known for his slick style off the pitch as well as on.

He used to wear a Zoot suit, snap-brimmed Trilby and in the words of Celtic hero Charlie Tully, “a pair of yalla shoes”, when out in Glasgow.

Heron was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1922, before moving to Canada as a youth where he joined the Canadian Air Force and played for a military team.

He turned out for Detroit Corinthians, then Detroit Wolverines, where he became the top scorer in the North American Pro Soccer League in the 1946 season.

He was spotted by a scout from Celtic when the team were touring the US that year.

Heron also made appearances in the Jamaican national team. But he signed for Celtic in 1951, a time when the game was dominated by physical players and despite having been a boxer, Heron struggled at the club.

He played five times before moving to Third Lanark, then Kidderminster Harriers, after which he rejoined Corinthians.

Son Gil Scott-Heron, described as the “Godfather of Hip Hop”, got global acclaim for The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.

At a book launch in Glasgow, Scott-Heron, said: “My father still keeps up with what Celtic are doing. You Scots always mention my Dad played for Celtic.

“It’s a blessing from the spirits. That’s two things Scots love the most – music and football – and they got one representative from each from my family.”

Celtic FC said: “The thoughts and prayers of everyone at Celtic are with Gil’s family.”

15 GOALS IN EIGHT GAMES AS TOP US SCORER, 1946

1956 CAREER ENDS.

WORKS AS REF UNTIL 1968

Gil Heron, 81, father of Gil Scott-Heron, joins the ancestors

By Norman (Otis) Richmond

Gil Heron, who was known as the Black Arrow has joined the ancestors.

Heron was 87 years old, a poet and professional soccer player.

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1921, he was the father of the revolutionary author/poet/singer and musician Gil Scott-Heron, who received much critical acclaim for one of his most well-known songs,” The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”.

Gil Heron passed away in a nursing home in Detroit on Nov.27.

Heron is survived by three children: Gil, Gail and Dennis. Another son, Kenny, was killed in a drive-by shooting in Detroit. He is also survived by eight grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

One of Heron’s surviving brothers, Roy Heron, was featured in a 2008 article,” At 85, Roy Heron’s a leader”, in Share newspaper by Dr. Lorne Foster.

Dr. Foster wrote then: “Heron has been a stalwart in African Canadian life and politics for over 60 years, fiercely dedicated to the principles of self-determination and consciousness-raising. He has single-mindedly maintained the same impassioned commitment to social justice that he possessed when he arrived in Canada in 1941.”

After Scott-Heron’s last performance in Toronto at the El Mocambo, he introduced “Uncle Roy”.

Roy Heron, remembered his younger brother with the following statement. “He was a brilliant person who showed people of color what they can achieve.” The older Heron attended his brother’s funeral in Detroit.

Gil Heron moved to Canada as a boy, and is believed to have first shown evidence of football skills during a spell in the Royal Canadian Air Force. He moved to the USA after World II and joined the Detroit Wolverines. Heron played in the United States and was invited to Scotland for a public trail at Celtic Park on Aug 4, 1951, scoring twice in the game.

According to press reports from Scottish newspapers: “The club signed him and he made his debut on August 18, 1951 in a League Cup tie against Morton at Celtic Park. He scored once in a 2-0 victory.

Heron was a published poet. One of his books was entitled, “I Shall Wish For You”. He was featured in a 1947 Ebony magazine article which referred to him as the “Black Babe Ruth.“ I spent many hours in the library at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) looking for that article, to no avail.

I met Gil Scott-Heron in the summer of 1976 when he made his first Canadian appearance at the world-famous El Mocambo. I interviewed him at a downtown hotel and asked him about his father. Arista records publicity campaign had gone to great lengths to point out that Scott-Heron’s father, Gil Heron, had been a professional soccer player for Scotland. Scott-Heron appeared to be taken aback. “The Scotts raised me” was his acid reply.

Scott-Heron was born in Chicago, but spent his early childhood in the home of his maternal grandmother, Lillie Scott, in Jackson, Tennessee. His mother, Bobbie Scott-Heron, sang with the New York Oratorial Society.

At the time of my first meeting with Scott-Heron he had not met his father. It was at that time I met his Jamaican-born uncle, Roy Heron, Aunt Noreen and cousins Melissa and Kathleen.

Heron was at Celtic for a year, making five appearances and scoring two goals before joining Third Lanark.

He eventually returned to the United States and settled in Detroit. He was also the father of jazz musician and composer, Gil Scott-Heron, who received much critical acclaim for one of his most well-known songs: “The Revolution Will Not be Televised.”

After the show with Scott-Heron and the Midnight Band, people hung out on that warm summer night at College and Spadina. Many of us watched Scott-Heron get into a taxi cab with three women. An African-Canadian sister confronted me outside the club and said, “I just saw your boy, Gil Scott-Heron, get into a cab with three White women.”

I replied, “I saw him too and the three women were his aunt and two cousins.”

Scott-Heron finally met his father when he was 26. The meeting is immortalized on the “Bridges” album on the song “Hello Sunday! Hello Road!”

Says Scott-Heron:

”Manager we had just couldn’t manage

So midnight managed right along

And it’s got me out here with my brothers

And that’s the thing that keeps me strong

Say Hello Sunday, Hello Road

Seems like Midnights’ coming up on a town

The children on their way to Sunday school

I’m tippin’ my hat to Miss Chocolate Brown

And it was on a Sunday that I met my old man

I was twenty-six years old

Naw but it was much too late to speculate

Say Hello Sunday, Hello Road

Hello Sunday, Hello Road“

When Bob Marley became too ill to perform, Stevie Wonder invited Scott-Heron to replace Marley on that tour. The Toronto Star assigned me to cover the concert and interview the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World,’ Stevie.

I ventured to Montreal only to discover that my soon-to-be friend, Dick Griffey, a concert promoter, president of the Black Music Association and head of Solar records– was the promoter of this concert.

I was reunited with Scott-Heron in Montreal and he introduced me to his wife at the time, the Shreveport, Louisiana born actress Brenda Sykes.

When I was introduced to Ms. Sykes I joked: “My Uncle Printis married Rose who I believed was a Sykes and she was also born in Louisiana. We may be cousins by marriage.”

In a telephone conversion with my aunt she confirmed that Brenda is indeed her cousin.

It was in Montreal that I first met Scott-Heron’s brother, Dennis. Besides being a bit lighter in complexion than his brother, there was no doubt about it they were blood brothers. Dennis went on to manage his brother for a time.

Scott-Heron spoke about his father on one of his last tours of Scotland. Said Scott-Heron, “You Scottish folk always mention that my dad played for Celtic. It’s a blessing from the spirits”.

It has become a tradition among Scott-Heron fans to show up at his Glasgow shows in Celtic tops.

At one concert, he joked: “There you go again – once again overshadowed by a parent.”

Norman Richmond is a Toronto-based writer/broadcaster/human rights activist. Richmond can be reached Norman@ckln.fm

‘THE FLIGHT OF THE HERON’

Michael Marra, the singer-songwriter who hails from Lochee in Dundee, recently wrote this song in tribute to Gil Heron and his time at Celtic. An excerpt from the song can be heard on his official site: http://www.musical1.com/Michael_Marra/#

(The site also contains a Marra song about another Celtic player, Hamish McAlpine, and the visit of Princess Grace of Monaco to Tannadice when he kept goal there).

GIL HERON – POET

Perhaps taking a leaf from his well-known son’s book, in 1992 Gil had his first collection of poetry published at the grand old age of 70.

Included in the collection of poems is one about his playing days in Scotland some four decades earlier entitled ‘The Great Ones’:

The Great Ones

I’ll remember all the great ones

Those that I have seen,

Those who I have played with

Who wore the white and green.

There was Tully and Bobby Evans

No greater ones you’d see,

And Celtic Park was our haven

To win was our destiny.

There was Sammy Cox and Thornton

Woodburn was there too,

Waddell and the great George Young

Who wore the white and blue.

There was Reilly and Turnbull for the Hibs

Billy Steele the great Dundee,

I’ll remember all the great ones

Wherever I may be.

So let there be a Hall of Fame

The fans will all be there,

The stars will all be remembered

By loved ones everywhere.

Meeting Gill Scott Heron (son of Gil Heron)

(From the Guardian website 1 June 2011)

It probably makes sense to tell you of the only time that I met Mr Heron.

This would be about six years ago, possibly more.

(I confess to having been In The Bottle up until this year and my memory is sadly somewhat decimated)

I learned that he would be present at the now defunct Fopp record shop on Edinburgh’s Cockburn Street, signing books, records and suchlike.

I was happy that my friend Pat was free to make the trip uptown from Leith as he shared with me, well many things, but most of all we shared an appreciation for this man and his various works.

We got to the record shop and by the ground floor counter and tills sat Mr Heron and his publisher and friend Mr Jamie Byng of Canongate Publishing, known to us from his Soul/Funk club-night Chocolate City, perched on stools and seeming to enjoy the interaction. Good humour was plain to see.

There was a fair queue and GSH took time to gently and courteously put people at ease, asking how they fared and what was going on. It’s not overstating matters to say that he was radiating benevolence after some very trying times.

I saw several years later a similar maturity and calm in Love’s Arthur Lee after not dissimilar trials and tribulations.

Anyhow, I was pretty rigid with apprehension and my friend laughed at a pretty evident case of starstruck on my part. Spellbound I was.

He encouraged me to wait in line and talk to the man.

And so I did. Eventually it was my turn.

I took a book from my courier satchel and found the page I wanted.

Mr Heron turned to me and smiled. Slowly.

“Would you mind signing this, Mr Heron? Just if it’s okay. I can get something else if it’s not?”

He had an almighty great red, black and green leather bonnet on. Open-necked Moroccan kind of cotton shirt. An Egyptian Ankh around his neck on a thong. What a face. What character writ large across it. Such eyes. Like pools.

He looked down at my book, entitled Hampden Babylon (a book of scandals in Scottish football) and the black and white picture of his father Giles dashing in the green and white hoops of Glasgow Celtic Football Club at Celtic Park.

I worried then that this was perhaps an inappropriate thing to present to him.

And then slowly he began to laugh. A full-bodied, head-back, arms-shaking, whole- bodied guffaw of a laugh.

I relaxed considerably. He was really laughing. It was… magic.

I can’t tell you just how magic it was.

He was tired out and hadn’t realised what I was handing him and then it dawned on him.

“Oh, I’ll sign THIS alright! You bet. You have a name?”, he said.

I handed him a pen and told him yes, I did, Dominic, but just his name would be beautiful.

He signed this marvellous flowing signature on the image, still composing himself as he did so and then gave the open book and pen back to me with a broad smile.

“Thank-you very much Mr Heron”, I said.

“You’re most welcome Dominic”, he replied.

I left the shop and found my friend outside.

“I told you he’d sign it”, my friend said.

After some confusion on my part, the book now resides with that friend in New York City and I am happy that this is so. He appreciates such things.

He appreciated

Ottawa Journal, 18 August 1951

The Story of Gil Heron: The First Black Professional Footballer in Scotland

Lee McKeown, BSSH Scotland Webmaster

https://scottishleisurehistory.wordpress.com/2015/08/11/the-story-of-gil-heron-the-first-black-professional-footballer-in-scotland/

Gilbert Heron (1922-2008) is best known for becoming the first black professional soccer player in America and as the first black professional footballer to play in Scotland for Celtic Football Club in 1951. He is also known as being the father of the jazz musician Gil Scott-Heron. Born in Jamaica, Heron would move to Canada as a child and would eventually play football in America for the Detroit Corinthians and later the Detroit Wolverines. Heron would prove to be a successful striker and became top scorer of the 1946 North American Soccer Football League. In 1947, Ebony magazine even described Heron as the ”Babe Ruth of soccer”.

Heron was no ordinary sportsman. He took part in a variety of different sports with Dimeo & Finn (2001) stating that Heron ”was an all-round sports man who ran and boxed and, while in Glasgow, played for leading Scottish cricket clubs too”. In 1940 Heron was even the 1940 boxing Golden Gloves champion of Michigan. BBC Caribbean describes Heron as a ”sporting renaissance man” due to his success in a wide variety of sports. While Heron enjoyed success in a variety of sports, it is his time in Scotland that he is arguably most famous for.

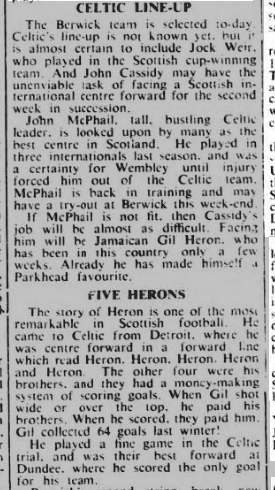

According to Wilson (2013), during the summer of 1951, Celtic would embark on a tour of America following a successful 1950/51 season which saw Celtic win the Scottish Cup for the first time since 1936/37 by beating Motherwell 1-0 in the final with a goal from John McPhail. It was during this tour of America that Heron was spotted by Celtic. There are, however, conflicting reports of how Heron was noticed by Celtic. Some reports suggest that Heron played against Celtic in a match in Detroit while others suggest that he may have been tipped off. Nevertheless, Wilson states that Heron who was discovered in Detroit quickly earned the nicknamed of the ”Black Flash” due to his speed and skill with the ball. While Heron was paraded as the first professional black footballer in Scottish football history, he was not the first non-white to play in Scotland. Andrew Watson played for Queens Park during the 1880’s, winning the Scottish Cup. Additionally, the Indian player Mohammed Salim was given a trial by Celtic in 1936 although he did not accept it and thus never played a first team game. Interestingly, Salim played in the reserve trials bare footed and refused to wear football boots as he had previously played bare footed in India.

Gil in Wolverines jersey

(Gil Heron in 1947 with the Detroit Wolverines)

Nevertheless, Heron saw the chance to sign for Celtic as a golden opportunity, claiming in a 1951 interview that ”Glasgow Celtic was the greatest name in football to me”. Heron was given a public trial against a selection of Celtic players divided into green and white teams and scored 2 goals. He impressed Celtic chairman Robert Kelly and was offered a 1 year contract which he accepted. However, this public trail was not a one off event to display the skill of Gil Heron. Celtic had a free public trail at the start of each season during the 1950’s and 1960’s to parade potential new signings to the general public. Gil’s son Gil Scott-Heron (2012) described in his autobiography that the contract offer from Celtic was a ”Jackie Robinson-like invitation for him. It was something that had been beyond the reach and outside the dreams of blacks”. Indeed, Jackie Robinson had been the first black to play professional baseball in Major League Baseball when he was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Previously, black professionals had only played in the segregated Negro Leagues and Heron would follow in the footsteps of Robinson by breaking down racial barriers by becoming the first black professional footballer in Scotland. Heron would make his Celtic debut on August 18th 1951, with The Ottawa Journal of Ottawa, Canada, reporting that day that ”for the first time in Scotland’s soccer history an American star will play for one of Scotland’s most famous clubs, Glasgow Celtic”.

GW334H497

(The Ottawa Journal, 18th August 1951)

Heron’s debut would be in a League Cup match at Celtic Park against Morton and he would score the second goal in a 2-0 victory in a match with over 40,000 in attendance. The goal he scored was impressive as Heron swiftly struck the ball on the turn inside the penalty area against Scottish internationalist goalkeeper Jimmy Cowan. Heron would again score in a 2-0 win over Airdireonians on 29th August. In a counter-attack Heron ran with the ball from the centre-circle and unleashed a stunning 20 yard strike against Fraser who was also a Scottish internationalist goalkeeper. However, despite showing earlier promise, Heron would have difficulties at Celtic. It has been claimed that a major factor why Heron did not succeed was because was not a physical player and struggled to adapt to the Scottish game.

Gil playing pool snooker John Glass portrait

(Gil playing pool)

However, Celtic historian Tom Campbell believes that existing players in the Celtic squad did not like Heron. It has been suggested that established stars such as Charlie Tully and John McPhail possessed significant influence in the dressing room, which Celtic manager Jimmy McGrory did not properly control. Campbell (2008) states that ”there were definite cliques within the club. McPhail was a charismatic character, he was the centre forward and he’d won the Cup for Celtic in 1951, but I think the other players kind of played to him, and almost visibly resented any player trying to take his place. There wasn’t quite the professionalism there should have been”. Heron was seen as a threat to the popular John McPhail and often found himself isolated on the pitch. Bobby Collins, though, was not impressed with the treatment of Heron and showed his disapproval by refusing to pass into space for McPhail in a match against Third Lanark. While McPhail and Tully saw Heron as a threat, he did have friends at Celtic, with Sean Fallon in particular befriending the Jamaican. However, it must be pointed out that the treatment towards Heron was not personal or racially motivated. Campbell claims that Leslie Johnson, another striker, was also treated in a similar fashion as he was also considered a threat to McPhail’s place in the team.

Eventually, Heron was relegated to the reserves where he would score 15 goals in 15 appearances. Despite his successful reserve scoring record, Heron would not play again until December in a 2-1 victory over Partick Thistle, however, he failed to impress on his return. While Heron was not recalled to the first team, he would be called to the Jamaican national side to play a series of matches against a Caribbean all start side in February 1952. Heron would score 4 goals in 3 games in front of a combined audience of over 70,000.

jamaica-intl-poster

(Jamaica v Caribbean All Stars poster 1952)

Another reason why Heron was unsuccessful at Celtic may also have been his poor disciplinary record. Heron was red carded in a reserve match against Stirling Albion on January 2nd 1952 for fighting an opponent. Celtic chairman Robert Kelly did not look favourably towards players with poor discipline and Heron’s days at Celtic appeared to be numbered after this incident. The season would prove to be a failure for Celtic, finishing in lowly 9th place and winning no trophies. As a result, Heron would not be offered a new contract. Following his release from Celtic, Heron would be signed by Third Lanark who were at the time also a respected member of the Scottish top division. Heron would go onto play 7 games in total for the Thirds at the start of the 1952/53 season. All 7 games Heron played where in the League Cup and he scored a total of 5 goals during his time at the club, with 2 goals being scored on his club debut.

It wasn’t just football that Heron played while he was in Scotland. During the summer of 1952, Heron would play for Poloc Cricket Club in the south of Glasgow before signing for Third Lanark. He would also play for Ferguslie in Paisley during the summer of 1953. After leaving Third Lanark, Heron moved to England to play for the Kidderminster Harriers for season 1953/54. It was a bright start for Heron before he was eventually relegated to the reserve team, similarly to his time at Celtic. Heron was forced to leave the club at the end of the season due to the club suffering financial difficulties which forced them to sell a number of their star players. After leaving the Kidderminster Harriers Heron would return to Detroit with his second wife who he had met at Celtic, and they would go onto have 3 children together.

While Heron did break racial barriers by becoming the first black professional footballer in Scotland, his appearance would not lead to a significant change in racial attitudes. According to Onuora, (2015) a black player would not play in the top flight of Scottish football again until Mark Walters played for Rangers against Celtic on 2nd January 1988. While Walters was indeed the first black player to play in the Scottish top flight since Gil Heron, Paul Wilson who played for Celtic in the 1970’s was mixed race. Born in India, Wilson had a Scottish father and a Dutch-Portuguese mother who had ethnic links to Africa. In 1975 in a 1-1 draw against Spain, Wilson became the only non-white player to be capped by the Scottish national team during the 20th century. Wilson was subject to racial abuse, and in a 2011 interview he stated ”I got it right bad but was strong and able to never react, retaliate or gesture because I had grown up with all this racism. I got so much stick at school and beyond.” While the signing of Heron did not lead to a significant change in the public attitude, it was nevertheless a step in the right direction. Heron may not have been a footballing success in Scotland. However, his is warmly remembered as a cult hero and as a pioneer for being the first to cross the professional colour line of Scottish football during a time when blacks were not yet considered equal to whites.

Note – Special thanks to the author of The Shamrock article The Noble Stride – Celtic and the Pioneering Herons for providing a great amount of information as well as the images used in this article. Thanks must also go to the Celtic historian Tom Campbell and Third Lanark historian Bob Laird for helping to provide information about Gil’s playing days in Scotland.

THE NOBLE STRIDE – Celtic and the Pioneering Herons

22/05/2014 The Shamrock 6 Comments

https://the-shamrock.net/2014/05/22/the-noble-stride-celtic-and-the-pioneering-herons/

“My father still keeps up with what Celtic are doing. You Scottish folk always mention that my Dad played for Celtic, it’s a blessing from the spirits! Like that’s two things that Scottish folks love the most; music and football and they got one representative from each of those from my family!” – Gil Scott-Heron, 2008

When the influential African-American singer and writer Gil Scott-Heron died in May 2011, Chuck D of the legendary hip-hop act Public Enemy put this message out on Twitter:

Image

Rappers Eminem, Snoop Doggy Dogg and Kanye West queued up to pay tribute to the man referred to as ‘the Godfather of Rap’. Ghostface Killah from the Wu-Tang Clan wrote: “Salute Gil Scott-Heron for his wisdom and poetry! May he rest in paradise.”

Paradise was something his father knew all about . . .

Rewind 60 years. Celtic Park, 18th August 1951. Celtic take the field against Morton in the League Cup before a 40,000 crowd. The star attraction is a new centre-forward fresh from Jamaica by way of Detroit. That summer Celtic had toured the United States and in Detroit they heard stories of a scoring sensation. Celtic Chairman Bob Kelly told the Daily Record: “We never saw him play but the word about him was so good that I invited him over to have a test. He satisfied and thus he was signed.” The Jamaican also satisfied in the game against Morton, living up to the pre-match hype. Despite having an early goal disallowed he added Celtic’s second in a straightforward 2-0 victory in the 35th minute with a 20 yard strike past Jimmy Cowan, the Scotland goalkeeper – grabbed the headlines with an all-round impressive display.

It wasn’t just his ability that was making the news – his race was a major talking point. A Daily Express matchreport said: “Make no mistake about it, Celtic have struck a black bonanza in Giles Heron”. In no time at all he had been conferred with the nicknames The Black Arrow and The Black Flash by the Scottish media and fans.

Image

For Gilbert St Elmo Heron this chance to play for Celtic was an opportunity that he simply could not let pass. Yet, he was considered a footballing pioneer even before he became the first Afro-Caribbean to play the game professionally in Scotland. Gil, often referred to as Gillie (and incorrectly as Giles), had been the first black man to play professional soccer in his adopted home of the United States and, playing for the Detroit Wolverines in 1946, was the top goal scorer in US pro football. Being top scorer didn’t translate into top earner however – the endemic racism in American society at the time meant that Gil’s pay was a quarter of the higher-profile white players in the North American Professional Soccer League.

ImageGil in his Detroit Wolverines jersey: ‘Top pro scorer Gil Heron weighs 160 pounds, is unmarried, has five brothers who also play soccer. He is rated the No.1 offensive start inthe North American League.’

His success in Detroit led to him moving to Chicago to join the leading club Sparta in 1947. While in Chicago he met Bobbie Scott from Tennessee and within a year they were married – with a baby on the way. The son would become a musical pioneer, named after the footballing father but also in recognition of his mother’s family, and was born on 1st April 1949: Gil Scott-Heron. In his 2012 autobiography he recalled being told stories of his father’s battles on the football pitches of Chicago: “His skills would offend the opposition, often leaving them feeling foolish and flailing, victims of Gil’s fancy footwork. There were scoundrels in places like Skokie, a suburb of Chicago then inhabited primarily by Europeans, who treated soccer like an ethnic heirloom. My mother talked about incidents when opposing players had felt forced to foul, going for his legs instead of the ball, not trying to tackle him but to injure; these were red flags to his temper.”

Gil and his temper were no strangers, as Celtic would later discover. While in Chicago he was suspended after being sent off in a game against Hansa, a German-American club, for retaliating against an abusive centre-half. He loved football though, having played since his youth in Kingston. As a 13 year old in 1935 he had been caught removing a regulation football from a store without paying for it. Four years later he left Jamaica for Michigan with his mother and brothers, also football mad: on one occasion four of the Heron boys turned out in the same game for Detroit Corinthians. Football was in Gil’s blood.

ImageGil, 1947, Detroit Wolverines

It had also made him a name in Black America. In 1947 he was the subject of a flattering profile in Ebony magazine (still the thought-leader on race issues in the States today) which highlighted his significance as the first professional black soccer player. The article noted his key attributes: “ball-control, agility and deception rather than his speed that makes him the great soccer player he is now.” The three-page spread paid the huge compliment of referring to Gil as ‘the Babe Ruth of soccer’: the baseball legend was America’s greatest sporting hero of that generation.

Later in 1976, visiting the headquarters of Johnson Publishing in downtown Chicago for an interview, Gil Scott-Heron met John Johnson, the publisher of Ebony and said: “I just came through to see if I could get a write-up in Ebony like the one you did for my father.” Johnson, unaware of the family link, led him on a search through the basement archive where together they recovered a copy of the 29 year old magazine, to the son’s great excitement.

Despite his goals, Gil received little publicity in the mainstream press nor was he asked to undertake the promotional work for the league that white players were offered. This might explain the significant decision that Gillie took in 1951.

After making contact following their return from the USA tour, Celtic had sent Gil a tourist ticket for the ship SS Columbia which was due to depart from Montreal on 24th July 1951. There was no guarantee of an extended stay in Scotland though. The invitation was simply to take part in the traditional pre-season public trial where the Celtic playing staff were separated into “greens” and “whites.” If he impressed, then he might be offered a professional contract – or re-join the Columbia on its return voyage.

It was a life-changing decision for all three Herons, as the son later described in his autobiography: “My mother and father separated when I was one and half years old, when Celtic, in Glasgow, Scotland, offered him a formal contract. My father decided to take an opportunity to do what he always wanted to do: play football fulltime, at the highest level, against the best players. It was, for him, the chance of a lifetime, the chance to play for one of the most famous teams in the British Isles. It was an opportunity to see who he was and what he was, to avoid sliding through fits of old age and animosity and spasms of “I coulda been a contender” that no one believed. That sort of thing can even make you doubt yourself, doubt what you know, doubt what you would have sworn if anyone was willing to listen. To play with Celtic was also a Jackie Robinson-like invitation for him. It was something that had been beyond the reach and outside the dreams of Blacks.”

For Gil Scott-Heron to describe Celtic’s offer as a “Jackie Robinson-like invitation” is especially significant. In 1947, Brooklyn Dodgers made Robinson the first African-American to play professional baseball in the modern era, effectively ending racial segregation in America’s most popular sport and boosting the nascent Civil Rights movement.

Image

While there was no formal segregation between the races in British sport, only a handful of non-whites had ever appeared in the professional ranks of football. This helped explain the fascination and fuss over Gil Heron’s appearance in the Hoops in 1951. For his son to adopt the stance he does is very forgiving as the decision to board that ship to play for Celtic effectively destroyed his parents’ marriage – and their own relationship.

Gil and Bobbie’s marriage was effectively condemned by his performance in the public trial on August 4th 1951: he scored two goals and was offered a one-year contract to become a Celtic player. Gil was staying in Scotland.

The club’s decision to offer a professional contract to a black player was a public demonstration that there was no colour bar at Celtic Park. In 1936 the Indian footballer Mohammed Salim had dazzled supporters in a couple of reserve games for Celtic but declined an offer from the club of a permanent contract, preferring to return to Calcutta where he was part of the successful Mohammedan Sporting Club. The only previous black player in Scottish football was Demerara-born Andrew Watson, a captain of Queen’s Park in the 1880s, who won the Scottish Cup and also captained Scotland to victory over England in 1881. Scotland, and the United Kingdom, had a relatively small black population in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

ImageAndrew Watson, centre rear, of Queen’s Park and Scotland fame

Things had moved on in post-war Britain though. The ship Windrush had arrived in England from the West Indies in June 1948 and heralded the start of an immigration boom. Race was very much a live issue when Gil Heron docked in Southampton to get the train to Glasgow in 1951. For Celtic Chairman Bob Kelly there were only positives in signing the Jamaican and he told the Glasgow Herald that he expected there would be a “drift of neutral followers of football to the novelty of a coloured player leading the Celtic attack.”

Gil’s successful debut against Morton made the news well beyond Celtic Park. The Chicago Tribune used the headline ‘Detroit Negro Scores Goal in Glasgow Debut’ and the New York Times reported that ‘US Player Helps Celtic down Morton in Glasgow Soccer, 2-0’ while a Canadian paper noted his nickname of ‘Black Flash’. New York’s biggest-selling black newspaper Amsterdam News also reported his debut: “Another milestone in sports democracy passed here last Saturday as a Negro for the first time played as a member of a big league Scottish Soccer team . . . Heron is not only the first Negro to play in big time Scottish soccer but also the first American to make the grade. This makes his feat doubly significant.” The Afro-American newspaper in Baltimore claimed that fans in Scotland had been “thrilled and astonished at the brilliance of a coloured American soccer star Gil Heron of Detroit.”

Image

Gil playing in front of the old Jungle enclosure at Celtic Park

As his fame grew Gil gave an interview in the Daily Record under the banner ‘Gilbert, The Broth of a Boy from Detroit’. Reporting that he was “the greatest thing seen at Celtic Park since goalposts arrived” the positive profile confirmed that he was a keen photographer who, if things didn’t work out, would happily return to his previous job as a “60 dollar a week painter in a Detroit motor plant”. Gil’s early observations of Scottish society may have raised an eyebrow or two from Record readers. He couldn’t understand why Glasgow “drops dead at 9pm” just when Detroit’s nightlife coming alive while he considered the Glasgow girls as pretty as anywhere else, but “they dress up to please their grandmothers and nobody else.”

Gil found friends in the Celtlic dressing room and Sean Fallon especially helped show him around his adopted city. The Jamaican was known for his colourful attire as well as his enjoyment of the nightlife. Charlie Tully recalled how he would turn out in a memorable pair of “yella shoes” when hitting the streets with his Celtic buddies.

On the field of play, Gil followed up his goal-scoring debut in the League Cup with a midweek game for the reserves against Hibs before re-joining the first team for a largely forgettable performance a week later against Third Lanark at rain-soaked Cathkin Park. One newspaper reported “Little was seen of Heron who had difficulty working up speed on the slippery turf and too often ran into offside traps.” He kept his place in the front-line for the midweek fixture against Airdrie at home four days later and, before a crowd of 25,000, impressed as he’d done on debut at Celtic Park. Celtic took an early lead through Jimmy Walsh and monopolised the play with Gil having two attempts that almost came off. It was third time lucky in the thirty seventh minute, as the Glasgow Herald reported: “the centre-forward took a pass from Baillie about midfield and side-stepping Dingwall on his run through released a tremendous shot from 25 yards which beat Fraser all ends up. The crowd applauded an effort which was as fine as has been seen on the ground for many a day.”

There were no more goals in the second half although Gil “revelled in the forward play and had another great try which Fraser saved at the foot of the post.” Fraser was the second internationally-capped keeper that Gil had beaten in his first fortnight with Celtic. The ‘Black Arrow’ was flying.

Gil retained his place in the first-team when they travelled to Greenock to play Morton on 1st September 1951. Celtic went down to a shock 2-0 defeat in a game marred by crowd trouble including pitch invasions; a third goal would have knocked Celtic out of the League Cup. The Evening Times’ view was that the Celtic forwards weren’t playing as a line and the return of the experienced John McPhail, whose goal had decided the Scottish Cup final in Celtic’s favour back in May, was “eagerly anticipated.”

ImageEnjoying a Scottish summer – Gil and Celtic team-mates Roy Milne, Alex Boden, Jimmy Mallan, Sean Fallon & Johnny Bonnar visit Largs in 1951 with partners

Gil was back in the reserves where he stayed until, with McPhail dropped after a ‘mystery’ trip to New York, he led the line against Partick Thistle at home in the league on 1st December. “Gil Heron received tremendous vocal support” reported the Daily Record. “He tried hard with little luck.” Celtic ran out 2-1 winners in the absence of McPhail and Tully but Gil didn’t score, and failed to impress. This was a missed opportunity. Celtic’s league performances had been poor and they were lying in ninth position. Monday’s Evening Times commented on Celtic’s options at centre-forward and inside-left: “In the matter of suitable reserves they are ill off in those positions.” The following week McPhail was restored to the front-line and Jim Lafferty, just signed from junior team Arthurlie and playing at centre-forward, scored both goals in a 2-1 victory over St. Mirren. It was back to the reserves and out of the limelight for Celtic’s Jamaican.

Image

Things did not improve after the new year for Celtic’s lacklustre first team. A first round exit from the Scottish Cup in February was followed by a further drop in the League placings to 13th. And yet, despite having scored 15 goals in 15 matches for the reserves, Gil still wasn’t recalled to the first team. He was still wanted though. In February he was called up by the Jamaican FA alongside Lindy Delaphena of title-chasing Sunderland – the first professional Jamaican footballer in England – to take part in a series of challenge matches against a Caribbean All-Stars select. More headlines followed – “Heron is coming to prop soccer XI” reported Jamaica’s Gleaner newspaper on 12th February. The series of four games proved popular, drawing in a combined attendance of over 70,000, and Gil scored 4 goals in the three matches he played. It had proved a successful homecoming for the Jamaican bhoy.

On his return to Scotland though he continued to languish in the Celtic reserves. There were lazy suggestions in the media that he couldn’t adapt to the poor weather conditions (contradicted by his scoring record in the first and second elevens) and there has been speculation since that being in competition for a place with John McPhail, an established first-teamer close to Jock Weir and Charlie Tully, didn’t help Gil’s cause. This argument has been made by Celtic historian Tom Campbell who claims that a previous centre-forward signing in 1948, Leslie Johnston from Clyde, was frozen out in favour of McPhail who also had friends among Scotland’s sport-writers (and later became a football writer himself). The influential columnist Waverley in the Daily Record had stated after one match that “Heron’s place is in the reserves” and that “The sooner McPhail is back in the Celtic team, the better for Celtic’s prospects.”

There may be an element of truth in these explanations but events on January 2nd 1952 could also explain why Gil Heron never found favour with the Celtic management team again. Playing against Stirling Albion reserves that day, Gil was sent off for brawling with an opponent. In addition to being suspended for a week he was also fined a week’s wages by the club. The Celtic Chairman, Bob Kelly, was a strict disciplinarian who frowned severely on such misconduct. During his reign players including Pat Crerand, Mike Jackson and Bertie Auld were sold by Celtic after falling foul of the Chairman, usually for indiscipline. It seems likely that the on-pitch brawl put paid to Gil’s chances of playing in Celtic’s first team again.

Celtic ultimately finished season 1951-2 in 9th place in the League with no silverware to show. In May Gil Heron was told that his one-year contract would not be renewed: the dream was over. He told one newspaper: “I may go home. I wouldn’t get the same thrill from another club.” He enjoyed life in Scotland though and was in no rush to return to the States and abandon his career in professional football. There was another important reason for staying put: Gil had fallen for a local woman, 23 year-old Margaret Frize.

ImageCrest of Poloc Cricket Club

Gil didn’t sit still that summer. As with most Jamaicans he had a fondness for cricket and he joined other West Indians in the ranks of Poloc Cricket Club in the city’s south side and was back in the papers again (“Footballer Gil Forces A Cricket Draw”). With the new football season dawning he was signed up by Third Lanark (“Hi-Hi-Hi for Heron” said one headline) and got off to a flier with two goals on his debut, yet within a couple of months he fell out of favour there too. The summer of 1953 saw him head to Paisley with his cricket bat to pay for Ferguslie. He was picked up again by another club for season 1953-4 – but had to cross the border to join non-league Kidderminster Harriers in the English Midlands. The pattern repeated itself: a bright start before being relegated to the reserves. Financial problems caused the club to get rid of its few professional players and Gil was transfer-listed in March 1954. The adventure was finally over – the footballing pioneer returned home to Detroit in July.

Scotland was never far from Gil Heron’s heart though. Margaret Frize crossed the Atlantic to join Gil the following year and, after the divorce from Bobbie was formalised, they married. This would not have been an easy decision for either of them: in the USA in the 1950s inter-racial marriage was outlawed in more than half of the country’s states. Not in Michigan though and it was there, in Detroit, that Gil and Margaret married and lived together, going on to have three children. Gil returned to the Ford Motor plant and to amateur photography but his love for the beautiful game never waned – he was a referee in the Motor City area for many years. He lived until the grand old age of 86 when he passed away in December 2008.

– – – – – – – – – –

Image

21 year old Gil Scott-Heron, at the time of the release of his first album ‘Small Talk at 125th and Lenox’, 1970

After his father left for Scotland, Gil Scott-Heron was initially raised by his grandmother in Tennessee and then, following her death, was brought up by his mother in New York before leaving for college. His first album ‘Small Talk at 125th & Lenox’ had been released in 1970 when he was 20 years old and already a published poet and writer. One of his earliest songs, ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’, remains the most influential. His fusion of jazz, blues and soul with partner Brian Jackson took music in a new direction. ‘Lady Day and John Coltrane’ is a homage to two African-American musical icons whose status he came close to emulating.

Image

Equally important though was the political and social dimension to Gil Scott-Heron’s work. ‘The Bottle’ and ‘Johannesburg’ voiced his concerns about addiction and apartheid. He confronted race issues repeatedly with songs such as ‘Whitey On the Moon’ and ‘From South Caroline to South Africa’ and, sporting one of the best afros in the music business, was considered a militant at a time when Black Consciousness was at its peak.

Image

Scott-Heron supported Stevie Wonder on tour as part of the successful campaign to have Martin Luther King’s birthday declared a public holiday in the States. With songs such as ‘B Movie’ and ‘Raygun’ he confronted the right-wing values of the Reagan Presidency head-on in the 1980s. His recording career suffered as he fell victim to drug and alcohol addictions, being jailed intermittently between 2001 and 2006, yet he made a triumphant and unexpected come-back in 2010 with the album ‘I’m New Here’ which was released to critical acclaim, reflecting his standing as a pioneer of rap music and hip hop. It was a mantle he was never entirely comfortable with, telling a journalist once “I don’t know if I can take the blame for that.” After a European tour promoting the new album he died in May 2011, aged 62.

ImageMasterblasters: Stevie Wonder and Gil in concert

Backstage, after a concert in Detroit in 1975, Gil Scott-Heron was approached by a young woman he’d never met before. Gayle Heron took him home and introduced him to her father – his father. “Gil Scott-Heron, this is Gilbert St. Elmo Heron” she said, by way of re-introduction. A quarter of a century had passed since father and son had seen each other. It was an awkward meeting, as described by the son in the song ‘Hello Sunday, Hello Road’ two years later. But it was a beginning. The son developed a relationship with Gayle and his brothers Denis (who became his road manager) and Kenny and a relationship of sorts with his father and Margaret. The two Gilberts were never close but they remained in contact and developed a strong respect for each other – and their individual achievements.

ImageThe Pioneering Herons – father and son, backstage in Detroit, 1993

The connection between father, son, Celtic and Scotland was re-ignited when Michael Marra, the accomplished Dundee musician and songwriter, wrote the song ‘Flight of the Heron’ about Gil and the impact of his time at Celtic Park. Scottish football and its characters were a regular feature in Michael Marra’s songbook. The tribute to Gil is a beautiful, inspiring song laced with wonderful imagery which Michael later recorded with the band The Hazey Janes (in which his daughter and son play) in 2012 and released on the EP ‘Houseroom’. That was to be Michael’s final release as he passed away in October that year.

ImageThe inimitable Michael Marra – the ‘Bard of Lochee’

In 2008 the Scottish writer Gerry Hassan visited Gil Scott-Heron in his Harlem apartment and played a demo version of ‘Flight of the Heron’. He recalled how they were both almost moved to tears by the experience: “I had the privilege of experiencing Gil hearing for the first time this magical Michael Marra song – and as it hit just under its first minute – realise that this track was touching Gil’s heart! It was a wonderful set of moments, and it made me realise that in many respects as men and performers, Gil and Michael, shared many similarities, being soft, wonderful men, who could both do with a bit of support in their lives, but I imagined had a lot of love.”

The first thing Gil did after hearing the song was write a note of gratitude to Michael for the tribute. He also declared the intention to cover the song himself. He never did. Time ultimately ran out on him, his father and the song’s author. Yet we have been left with an enduring musical testament to a true footballing pioneer . . . ‘Drawn by the flame of the beautiful game, here was a brother who could not stay home’

The Flight of the Heron by Michael Marra

When Duke was in the Lebanon

Grooving for the Human Race

Gil flew high in the Western sky

On a mission full of style and grace

From Jamaica to the Kingston Bridge

He was inclined to roam

Drawn by the flame of the beautiful game

Here was a brother who could not stay home

Higher

Raise the bar higher

He made his way across the sea

So that all men could brothers be

When Miles was in the juke box

and Monk was on the air

He crossed the ocean to the other side

To play for Celtic with the noble stride

The Arrow flew, he’s flying yet

His aim was true so we don’t forget

What it means when his name we hear

The hopes and dreams of every pioneer

Higher

Raise the bar higher

He made his way across the sea

So that all men could brothers be

Lyrics – copyright Michael Marra

Thank you to Michael’s wife Peggy for permission to re-publish the lyrics with the article.

To listen to the song on The Hazey Janes YouTube channel, click here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xprRxNVs_cY&feature=youtu.be

Thank you to The Hazey Janes for making the song available to hear online

Houseroom-Front-Cover-293×300

To purchase the album Houseroom which contains ‘Flight of the Heron’ click here: http://www.propermusic.com/product-details/Michael-Marra-and-The-Hazey-Janes-Houseroom-133127

The Hazey Janes have a new album out: http://thehazeyjanes.com/?page_id=2

‘He made his way across the sea

So that all men could brothers be’

Gil Heron: Soccer’s Jackie Robinson

June 8, 2016By Brian Bunk

Greetings_from_Detroit,_Michigan_(65811)Greetings From Detroit, Michigan. (Tichnor Brothers, Publisher [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons) http://werehistory.org/gil-heron/

The list of important black athletes from the era before sports became widely televised includes names such as Jack Johnson, the first African American to hold boxing’s heavyweight title; Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals at the 1936 Olympic games; and Wilma Rudolph, the winner of three gold medals in the 1960 summer games in Rome. As important as these figures are, their fame pales in comparison to that of Jackie Robinson. A talented athlete in many sports, Robinson made his name as the first African American to play professional baseball following the establishment of the sport’s infamous color line. In recent years his profile has only grown following the establishment of Major League Baseball’s Jackie Robinson Day in 2004 and the release of the film 42 in 2013.

But another man became the first black professional soccer player in the United States almost a year before Robinson took the field with the Dodgers. His name was Gil Heron and 2016 marks the seventieth anniversary of his debut on June 7, 1946.

Gilbert St. Elmo Heron was born in Jamaica on April 9, 1922. Like Robinson, he excelled in several sports as a child, including track and field and soccer. After his parents split up in 1938, he moved with his mother to the United States, settling in Cleveland where the family lived with an aunt. Once again, he showed himself a talented athlete. He lined up at running back for the Glenville High School Tarblooders football team while also boxing and playing baseball. Eventually, the family moved to Detroit. During WWII, Heron, who was still a British citizen because of his Jamaican birth, served with the Canadian Air Force. He spent most of his time in the service playing soccer and baseball.

After the war, Heron returned to Detroit and by 1945 was playing for the soccer club Venetia in the Detroit District Soccer League. His talent shone through as he scored an incredible 44 goals in just 14 games. A year later, a Chicago restaurant manager named Fred Weiszmann organized the North American Soccer Football League (NASFL) with squads in Chicago, Pittsburgh, Toronto, and Detroit. The idea of a pro soccer league was not new. The first in the US, and one of the earliest outside the United Kingdom, had formed in 1894. Although that league, the American League of Professional Football, folded after less than a year, big league soccer experienced resurgence when the American Soccer League (ASL) developed during the 1920s. The ASL featured a high level of competition and attracted talented international players, mostly from Northern and Central Europe. Although the original ASL collapsed following the Great Depression the competition eventually reformed as a mostly semi-professional organization. At first, the founder of the NASFL hoped to form a Midwestern section of the ASL but eventually decided to form a new league instead.

The 24-year-old Heron made his debut for the Detroit Wolverines on June 7, 1946 and quickly became one of the NASFL’s most exciting players. He scored a hat trick in the first league match played at Chicago’s Comiskey Park and went on to become the competition’s top scorer during its inaugural season. He also tallied a goal in the game that clinched the title for the Wolverines. Before the next season, Heron moved to the Chicago Maroons for what was reported to be “a substantial sum.” As a member of the Windy City team, he pocketed twenty-five dollars a game, the same salary he had earned the previous season in Detroit.

Although Heron is not well known today, the black press at the time regularly celebrated his accomplishments. In a 1947 article Ebony magazine called him the “Babe Ruth of Soccer” and noted that he was the only black professional soccer player in the country. The NASFL failed after just two seasons but Heron stayed on in Chicago where he married and had a son. He also continued to play soccer in the city, lining up for local powerhouses Sparta Athletic and Benevolent Association Football Club before returning to Detroit in 1950. Throughout his career it seems that he did not routinely suffer the same level of racial hatred as Robinson faced while integrating baseball. Nevertheless, as the only black professional in Chicago he was often singled out for abuse by other players and fans. After matches, his wife helped rub down his legs with alcohol in order to soothe the muscles and heal marks left by opponents’ studs.

Eventually Heron moved to Scotland and signed with one of the biggest clubs in global soccer, Celtic Football Club. For a variety of reasons he never really had much success in his two season with the Glasgow side but stayed in Britian for two more seasons while playing for Third Lanark and Kiderminster. After returning to Detroit in 1954, Heron faded into obscurity, his fame eventually eclipsed by that of his long-estranged son musician Gil Scott-Heron. For his talent as a player and his role as a pioneering professional black athlete during a period of intense segregation, Heron deserves wider recognition.

1952

Rare pic of a Scottish football league select team to play cricket at Poloc cricket club in Glasgow in 1952. Celtic’s Gil Heron and Rangers George Young are seen together

jamief

@jamiebhoy2009