Interviews & Articles

Interview

(below is taken from an interview in the “The Herald” April 20 2003, speaking to Douglas Alexander)

THE doorbell of the Bjork family home rang in a suburb of the Swedish port of Helsingborgs on the evening of June 25, 1978. As the door opened, a small boy with curly hair stood outside, clutching a football.

Was Fredrik coming out to play? Henrik Larsson, then six years old, was in such a rush that he couldn’t even wait for extra-time in the World Cup final between Argentina and Holland. He had bolted from the block of flats he lived in, desperate to be Mario Kempes or Leopoldo Luque, the Argentine strikers.

“I grew up in the flats, and just down from my house was the biggest grass field, and there all the kids used to come together and play different games of football. In summers, when everybody was off during the holidays, we used to go down and play football from early morning until mum called you in for dinner.”

Eva Larsson was a factory worker, and Henrik’s dad was Francisco Rocha, a sailor from the Cape Verde islands off Senegal on the west coast of Africa. He has an elder brother, Kim, from a previous relationship of his mother’s, and a younger one, Robert, who is also Francisco’s son.

He was named after his uncle Henrique but it was agreed that it would be changed to the Swedish Henrik, and that he would take his mother’s surname to help him fit in. His Christian name was soon abbreviated further to Henke by his childhood friends.

Patrick Vieira’s ancestors are also from the Cape Verde islands, but his family fled to Senegal when a drought hit the crops in the 1960s. Several members of Larsson’s extended family remain, and he hopes to go there with his father when he retires. “I would love to do that but you shouldn’t go only for one or two weeks, you should be there for longer to see everything because there is a lot of different islands. Hopefully, I will have the time soon to do that.

“My dad is still in Sweden and obviously if I am going I will bring him back. He will have to show me the language because unfortunately I don’t speak Portuguese. I would love to go back with him and see how he had it when he grew up, and see the family over there. My dad was a sailor, he’s an old man now, 72 in December. He was out on the sea, sailing all over the world on merchant ships. He ended up in Denmark first, then he came to Sweden.”

It was from his father that Larsson got his love of football.

“We always used to watch football. We had this programme in Sweden where they showed English games every Saturday. I used to sit up with him and watch European Cups, World Cups, European Championships, the Swedish national team. We watched it all. He loves football. Brazil was his favourite team and we always used to go for them when it was a World Cup.”

His father also rented him a video of Pele, which Larsson watched over and over. “If you look at Pele, he could score goals but he could also set up a goal. He has always been my idol.”

Larsson would pretend to be Pele and Brazil, and his pals would tease by asking to be teams like Poland instead, but there were also more sinister taunts to deal with. “I am not that dark but obviously I had my curly hair when I was young and you get people, who don’t understand, who will say something. I used to win the most fights as well, so it soon stopped.

“I can’t recollect feeling that different. I only had to look at my dad and I knew I wasn’t 100% Swedish, but when you are a kid you don’t have those worries. You just go on with it and that depends how the other kids are as well. There were times when people called you something. You always have the odd ones who will say something. You have bad people everywhere in the world and that includes Sweden.

“The older I get the more I say it is stupid people that are racists or whatever, and mostly it is because they are afraid. I don’t understand someone who hates someone else when they don’t know the person, just because he’s black, yellow or whatever colour you want to mention. For me, that’s just not comprehensible.”

Larsson remembers his childhood as a happy one, although his parents separation when he was 12 affected him deeply. “It’s a very vulnerable time of your upbringing, so that wasn’t easy. It took a lot of time before I could accept it, but that’s the way life goes sometimes and you just have to make the best of it.”

He admits he threw himself into football to forget and became particularly close to two coaches at Hogaborgs, Bengt Persson and Kenneth Karlsson. Persson passed away in 1999, but Larsson remains in regular contact with Karlsson, who was also a teacher at his former school. “I loved playing football at that time. I trained maybe twice or three times a week with Hogaborgs and the rest of the time I was out playing in games. I used to play with two different teams, so I had my mind on other things.

“Kenneth always used to look after me when I was at school. He more or less took my side if he saw somebody older bullying me. It wasn’t only with me, it was with every kid. I always felt I had support from him.

“Bengt was there as well with support when things weren’t going as I wanted it to go. The club was very important for my football education but also for educating me about life in general — about being polite and things like that. It was very important and I will never forget. I always try to give something back for what they gave me.”

As good as his word, Larsson sends cheques for any paid television punditry back to Hogaborgs BK and returns when he can to present the HenkeBoll, an award for the club’s most promising player under 16. “If I am home, I try to give that out, but mostly I am not.”

A quarter of a century on, Fredrik Bjork, the boy whose doorbell he rang that night in June 1978, remains his “best friend”.Pre-Celtic Career

DESPITE the good grounding with Hogaborgs, Larsson began to wonder if the dreams of becoming a footballer, which he had articulated in his school essays, would ever come true — especially when he was found employment as a fruit-packer and as a youth worker upon leaving school. “Looking back, I think that was very good for me. At that time, when I was 18, I had more or less given up hope of turning pro because, if you looked around you, there were players my age already playing at the highest level in Sweden. It made me realise that football wasn’t everything and there were other things to life as well. It maybe gave me a good distance.

“It is still life and death when you are out there, but it was terrible sometimes with me. I hated to lose, I really hated to lose. I still do, but it was maybe more of a disadvantage to me than an advantage, because I let it get to me too much.”

It was also around this time that he met Magdalena Spjuth — an uptown girl. She came from a posh suburb and was a keen horse-rider, her father was a prominent politician and her mother an education chief with the local authority but, like Henrik’s parents, they had separated in her teens.

She became Magdalena Larsson on Midsummer’s Eve 1996, and Larsson describes her stabilising role in his success as “very important”.

“I don’t care about money,” says Larsson, who reputedly earns £40,000 a week. “If you ask me how much I have, I wouldn’t have a clue. Bank managers I don’t speak with. My wife does all that.

“As long as I can have dinner and treat myself to a few things, I am happy with that. You won’t find me in Glasgow city centre every week, shopping. I have money so I can buy the things I want, but it has never been the most important thing in my life, even when I didn’t have any money.

“The people who know me, and there’s a lot of people in Scotland who don’t know me, but my friends back home know exactly. In that aspect, I haven’t changed at all.”

The new maturity started to translate into his performances. He went to Benfica, then managed by Sven-Göran Eriksson, to train, thanks to the influence of Mats Magnusson, the famous Swedish striker. Magnusson then returned home to Helsingborgs, Hogaborgs’ larger neighbours, and they signed Larsson as his partner. Sweden’s scoring torch was about to be passed between two generations.

“Mats Magnusson was the one that you aspired to because he came from the same club and went to Malmo, went to Switzerland, went to Benfica, where he’s as big as ever, and played in the national team. So you wanted to do the same. Deep down, I still believed I could do it. The hope is always there that you can achieve it.

“He was a very good player. A lot of people don’t understand how good he was because he also played in a smaller league and, when he was in Portugal, people used to say the same things about him that they say about me now.”

Larsson learned rapidly from Magnusson, scoring 34 goals in 31 games to help Helsingborgs back to Sweden’s top division. His admiration for his veteran partner increased as he watched him play through tremendous pain. “All that season he had trouble with his right knee. He was two-footed like Lubomir Moravcik, which was just as well because he had to go to the doctors every week and get the water out of the knee. He couldn’t play with his right leg all season. Incredible.”

Larsson continued to score in Sweden’s top division, helping Helsingborgs to fifth place, and found foreign clubs courting him when the Swedish season ended in the autumn of 1993. His choice was between Christian Gross’s Grasshoppers and Wim Jansen’s Feyenoord.

“Holland was a better league than Switzerland,” he explains. “Wim was only there for two months, then he went, then we had Willem Van Hanegem, who was quite alright, then Arie Haan. I didn’t play well in the first year under him.

“I played in a lot of different positions — left, right, anywhere you can imagine. The second year it started off good and I played as a striker, and then he started to change me after 50, 55, 60 minutes all the time, even if I was playing good. I had to get out of there, I had to get away. That wasn’t the way I wanted to play.

“I had a meeting with Helsingborgs at the Hilton Hotel in Amsterdam at the airport, but I told them that if something else came up, I would go straight to that because I didn’t want to go home to Sweden just yet. If you go home, you are a failure. Simple as that.

“I didn’t want to go home because there’s not many who go home and come out again. Then Wim came and saved me.”

Marcel Van der Kraan, a Dutch journalist, provided the crucial information, that Larsson had a clause in his contract that allowed him to leave if an offer of £650,000 was received, although the striker had to take the Dutch club to court to invoke it. During his signing press conference for Celtic, Larsson was questioned on suspicion of being damaged goods. “You might be good but you still have to prove it again, and I don’t think a lot of people knew me and knew who I was. Wim knew who I was and what he could get out of me, and I am just happy that he brought me here.”

Was it fate? “It’s hard to say no. You have to say yeah.”

The boy they couldn’t buy

Ian Bell (Sunday Herald)

10 Mar 2007

Ian Bell lauds the veteran Swede who in 10 weeks has shown English football up

Cliches are devices employed by the talentless to make genius manageable. We clods only make sense of the sublime with glib and meaningless phrases. Football, for whatever else it might be worth, proves the point.

Here’s a recent favourite. Every hack on the sofa offers it weekly. “Form is temporary,” they say, “but class is permanent.” They forget to add: “and then there’s Henrik Larsson”.

The little man was breaking hearts at Old Trafford last week. Sir Alex Ferguson was talking wistfully of how the Swede, if he chose, could be playing in the Premiership at 40. What he truly meant was a two-fold assertion.

First, that a player who could “only score in the SPL” has been more productive for Manchester United over 10 short weeks than certain starlets named Wayne. Secondly, that Ferguson’s club only earned the right to face Roma, next time, thanks to a little guy who prefers the wife and kids to another bucket of money. Champions League? Done that, won that.

In a world of non-genuises preening in their baby Bentleys, Larsson’s example is important. Ferguson taught him nothing. He exercised no patronage worth a damn and did not once dare to shout, bawl, or bully.

Larsson does not need his money, his glamour, or his psychosis. Here’s Henrik executing that inch-perfect strike when it matters most, almost for fun. Where’s David Beckham, at 32? Rodeo Drive? It’s not even funny.

Larsson is the best header of a ball since Denis Law: discuss. This isn’t a trivia quiz. Football’s pantheon contains any number of glorious failures. What counts most, finally, is the ability to take a craftsman’s care over the essential transaction: people pay money, I perform. That’s the deal.

The Premiership, bloated beyond all reason, has begun to lose sight of the fact. My guess is that Sir Alex is allowing himself another couple of years at Old Trafford in order to create yet another team: that’s his privilege, I think. That is, equally, the Manchester tradition.

But Giggs, Neville and Scholes, glorious as they have been, are enjoying their last hurrah. The team, like the coach, are no longer young, and the youngsters among them have yet to perform. What mattersnow is to transmit the virtues that Ferguson, raving like Lear, has embodied. Where’s the next Keane? Who might be the new Cantona? To put it no higher, the next generation had better not pin their hopes on Rio Ferdinand.

Instead, we have Rooney and Cristiano Ronaldo. Bobby Charlton, who may know a thing or two, has been lavish in his praise of the latter while appearing to ignore the former. I doubt that it counts as an accident. What was the Great Comb-over in his finest days, after all?

He was the teenager who survived Munich. Rooney needs a bit of pressure? Try living through that slaughter. Charlton was also the finest striker of a ball ever. That’s ever, italics, by the way. Even Pele deferred. When old Baldy says that Ronaldo can do things no-one else has ever done before, the praise is lavish beyond words, but the criticism is implicit: where’s Rooney?

Why is Sir Alex still failing to extract genius from the great, white, pasty-faced hope of English football?

Larsson’s goal against Lille should be shown in every coaching class there is. The marking was dire; Ronaldo’s cross impeccable: that much is beyond argument. But how do you teach anyone to lose every marker, to merely “pop up” just like that? And how do you instil an imperative: we need to win, always?

Ferguson will miss Larsson, I suspect, less for the fact that talismans who have scored in every competition offered are hard to come by, than for the example he personifies, unassumingly, at every time of asking. What could make a Ronaldo complete? What might make a Rooney understand that talent and application always go together? Here’s Henrik, 35 and rising, saying that there is nothing you can show him. Nothing at all.

The hubris of English football needs this kind of corrective. Even Ferguson, in his cussed way, probably needs it. The player who says, and means, that he keeps his word to his hometown team. The player who does not stoop to foolish jousts with his coach. The player whose “media image” was never the point, nor purpose, of his trade. And the player whose reticence is an implicit comment on all those silly boys with too much money.

Possibly the most impressive thing about Larsson is that he is not much impressed by “Sir Alex”. Old Trafford assumed, I think, that when the cheque book appeared the little Swede would succumb, just like all the rest. In that context, Ferguson’s press conference last week was almost funny. Apparently, “the boy” – but let’s call him a man – couldn’t be bought.

The chances of Rooney or Ronaldo learning the lesson are remote. Those kids have agents and advisers the way dogs have fleas: they are stuffed, daily, baffled and bewildered, with “advice”. But here was Larsson’s last tutorial. Football need not be dishonourable. You don’t need an accredited pimp. You don’t need to engineer “interest” from Madrid or Milan every Monday morning.You turn up. You train hard. You keep your word. If dreams come true, you score goals.

That ethic is missing at Old Trafford. I suspect, listening to Frank Lampard’s £100,000 a week contract woes, it’s missing at Stamford Bridge. I see no signs of a craftsman’s virtue in Liverpool, or at the Emirates Stadium. Great football clubs are owned by trading companies called players.

But who kept Manchester United in the Champions League? Who allowed the dreary nostalgics to say “that’s how you score a goal”? And who allowed us to remember that a genius is worth every penny he might ever earn from a shoddy craft?

Little Swede. Black. Rising like a bird at dawn. I can almost bear to watch football again.

Thank you, Henrik, and good luck.

Larsson on the Celtic years

by Brian Etherson, 17 October 2008

Former Celtic striker Henrik Larsson has spoken exclusively to Inside the SPL and admitted that the club signed him when no one else wanted him, especially Feyenoord for whom he was playing for at the time.

Now back in his homeland and playing for his first club Helsingborg, Larsson admits he loved every minute of his time with the current SPL champions, even when the going got tough.

“The club took me when nobody else really wanted me,” Larsson said. “I had seven fantastic years there even when it wasn’t that great.

“But I still enjoyed my life in Scotland and my family enjoyed the life as well.

“So it’s my club without a doubt.”

Larsson helped The Hoops win four league titles, and the most important one according to the Swedish hit-man was stopping Rangers winning 10 on the spin, although he was oblivious to the real meaning of it at the time.

“Obviously stopping Rangers getting ten in a row and it’s always going to be up there because it was so important,” added the Swede.

“I didn’t realise that, but during the season you found out how important it was for the fans and obviously for the players as well.

“We were a lot of new players who wanted to do something, but now afterwards I still get goose bumps when I think about what would’ve happened if we didn’t win that league [title].

“Because that would not have been good for Celtic, so that’s always going to be up there and the year when we won the treble as well.”

Two years ago, Larsson won the Champions League with Barcelona and five years ago with Celtic he lost to Porto in the final of the Uefa Cup, but the pain of ‘that’ night in Seville will live with him forever, because he believes Celtic could have beaten the side led by Jose Mourinho.

“There is no beauty in losing a final,” rued Larsson. “I still hate it when I talk about that evening.

“I don’t enjoy it all, I think we should have won that, we were capable of doing that against a very good side that went on the year after to win the Champions League.”

Larsson is the only ‘foreign’ player to be voted into Celtic’s greatest team and even now, he still finds the honour difficult to comprehend.

“It’s a great honour, maybe I don’t understand it now because I’m still young in terms of life, so I think it’s something I’m going to appreciate even more when I get older.

“It’s fantastic, but it just shows the mutual respect the fans and I have for each other.

“We had a great relationship over the years and I still hear it when I play here [Helsingborg] I still hear the songs over here and sometimes the Celtic jersey is going to be somewhere in the stand and I always smile when I see it because it’s just fantastic.”

Sweden legend Larsson retires

20 October 2009

Provided by: Al Jazeera English

Henrik Larsson, widely considered one of the greatest Swedish footballers in history, has announced his retirement.

Famed at club level mainly for his successful stint with Celtic and then at Barcelona, where he won the European Champions League, the striker said on Tuesday that he would end his career at the close of the Swedish season on November 1.

“I’m 38 now, it has been enough,” Larsson said.

“I enjoyed my career and I want to thank everyone who has supported me in all these years.

“Now it’s time for something else.”

Larsson is currently playing for home-town Helsingborg in the Allsvenskan league, although as recently as 2007 he was taken on loan by Manchester United to bolster their English title push.

Golden Boot

He won the Golden Boot as Europe’s top scorer in 2000-01 while at Scottish giants Celtic, where he is still known among fans as “the King of Kings.”

He played in three World Cups and three European Championships for Sweden, scoring 37 goals in 106 international matches.

“I will think things over what I would like to do. First I will need time to adjust to the non-football life,” Larsson said.

“What I do know now, is that I’m 100 per cent sure about my decision to end my playing career.”

Helsingborg sporting director Jesper Jansson said club officials had hoped Larsson would play another season, “but respect Henrik’s decision and feel tremendously grateful for all his contributions.”

Larsson started his professional career at Dutch club Feyenoord in 1993, when he was 22.

A year later, he was a substitute in the Sweden squad that finished third at the 1994 World Cup in the United States.

His biggest European club triumph came in 2006, when Larsson’s two assists helped Barcelona rally to beat Arsenal 2-1 and clinch their first European Champions League title in 14 years.

Larsson retired several times from the national team, only to come back when Sweden needed his skill and experience.

Surprise comeback

After two years focusing only on club football, he made a surprise comeback for Sweden at the 2008 European Championships.

Though remarkably fit for his age, Larsson had lost some of his goal-scoring edge, and didn’t convert during the tournament.

He also failed to score in Sweden’s unsuccessful qualifying campaign for next year’s World Cup.

His last goal for the national team was in a friendly against France on August 20, 2008.

Copyright 2009 Al Jazeera English.

Al Jazeera English

HENRIK LARSSON

by David Potter

The Celtic historian cannot yet give his definitive version on Henrik Larsson. Henrik has at least another half season to go, and more if, as we all hope, Martin can persuade him to stay on for at least another season. What we can say, however, without any fear of contradiction is that Henrik is the greatest Celtic player of our time and well worthy of a place in any team of all time Celtic greats.

Henrik Larsson’s statistics are stark enough – stupendously so – as he has scored 217 goals (at the time of writing, post Bayern Munich at Celtic Park in the Champions League) for Celtic and is en route to becoming the Club’s third top scorer of all time, behind Jimmy McGrory and Bobby Lennox.

Celtic and their fans need to have a personality goal scorer. McMahon, Quinn, McGrory all fitted that bill. Curiously enough, the Lisbon Lions did not really have one, with the possible exception of Bobby Lennox, for they were so good in other respects. But, in the 1970s, we had Dixie Deans and Kenny Dalglish, and in the 1980s (briefly and fitfully), Frank McGarvey and Frank McAvennie. The dreadful years of the early 1990s were characterised by the lack of such a person.

Yet Henrik does not court personality status. A quiet man, always dignified and reserved, yet very willing to give interviews when requested and also a man who knows all about what Celtic is meant to be for. His background is far removed geographically from the Irish immigrants to Scotland of 120 years ago yet, in his early days in Sweden, he was the subject of racial taunts because of his father who came from the Cape Verde Islands and his less than blonde hair. This will strike a chord with those who know anything about the origins of Celtic – the ignorance and prejudices of others is always something that many Celts have had to contend with.

Henrik was born on September 20th 1971 in Helsinborg, and played for the team of that name before moving to Feyenoord, winning his first Swedish cap in 1993 and starring in the World Cup of 1994 for Sweden. Yet he was more or less a complete unknown in Scotland when Wim Jansen brought him to Celtic in the summer of 1997, for what now seems a quite ludicrously modest fee of £660,000 – the best bit of Celtic business ever, perhaps.

His first appearance was distinctly inauspicious. He came on as a substitute at Easter Road and promptly gave to ball away to concede a goal (scored by Chic Charnley)! Oh dear, we thought. Foreign imports to Celtic Park in the 1990s had been far from encouraging. Had we got another duffer here?

Fortunately a brilliant goal against St.Johnstone a week or two later (a spectacular diving header) made us change our minds, and very soon the dreadlocks of Henrik Larsson became a feature of the 1997-98 season as Celtic returned to glory, winning the League Cup in November 1997 with Henrik inspired and then, thankfully, the Premier League Championship in May 1998, with Henrik Larsson crucial to The Cause – the end of ‘in-a-row’ and the preservation of our nine League Championships in-a-row as the benchmark, since we were first past the post.

It was Henrik’s goal (a tremendous 25-yard strike) in the first minute of that gut-wrenching last game of the 1997-98 season, on the 9th May against St.Johnstone at Celtic Park, that set us on the way to win that Championship. Less politically correct Celtic fans had by now adopted Henrik as one of their own claiming (no doubt to Henrik’s embarrassment):

“He wears dreadlocks

And he hates John Knox,

Oh, Henrik Larsson”

But this success did not last for Celtic immediately plunged themselves into self-destructive internecine strife and the next two seasons were barren ones (save for the winning of the League Cup in early 2000). Yet, things might just have been so different had Henrik Larsson not broken his leg (horrendously) in a European game against Lyon in November 1999.

But Celtic’s fortunes turned in summer 2000 with the arrival of Martin O’Neill and the restoration of Henrik Larsson to full fitness. By October 2000 the dreadlocks had gone (his new hairstyle making national news as a top item, as an indication of the status and regard for the man), but the skill and the goal scoring had returned.

It was a great season – a Treble winning season – though Henrik’s lovers were disappointed that he did not quite beat McGrory’s record of 50 domestic goals from 1935-36 or score a hat-trick in the Scottish Cup Final which would have put him on a par with Quinn and Deans. But, we had enough to be going on with, and songs like “Henrik Larsson is the King of Kings” resounded round Scotland’s grounds that season, as well as “The Magnificent Seven” in Paradise whenever he scored.

Henrik Larsson had become a Celtic talisman, a magician of a footballer, celebrated by Celts and feared by all others.

Also, it should never be forgotten, indeed it should always be revered, that Henrik Larsson scored 53 goals in all competitions in that glorious 2000-01, Treble-winning season, thereby earning the ultimate accolade for a striker in Europe – the Golden Shoe! Not a bad result for a player returning to his first season after such a horrendous injury.

The following two seasons perhaps had less to show in terms of silverware (though the Championship was retained in season 2001-02 in quite dominant and conclusive fashion), but Henrik’s form remained superb, both for Celtic and for Sweden in the 2002 World Cup.

It was not Henrik’s fault that Celtic lost the UEFA Cup Final of 2003 (his first goal being his 200th for The Hoops), for he scored 2 tremendous goals in Seville to cap a superb season in which it is sometimes forgotten that he came back from a broken jaw. And, it was certainly not Henke’s lack of goals that ultimately cost Celtic the league title by a solitary goal, as Henrik Larsson had netted 28 league goals and a total of 44 in all competitions in season 2002-03 – the season that we went so very, very far without just reward.

Henrik’s great goal scoring ability often hides the fact that he is also a marvellous player with uncanny ability to turn, to beat an opponent and to find a man with unerring accuracy. The Champions’ League game against Lyon at Parkhead in September 2003 showed how he could make goals as well as score them, as Henke’s precision crosses allowed for goals from Liam Miller and Chris Sutton to conquer the French Champions.

His aeroplane impersonations after scoring a goal have now become a cliché for he has had loads of practice. It is noticeable, however, that after he scores he always runs to the crowd to share his joy with them, as well as pointing to his wife, Magdalena, in the main stand and kissing his wedding ring. In this respect, Henrik is a true Celt, and it is his interaction with and appreciation of The Faithful that makes our relationships at Celtic so special – the bond between fan and player seems totally unshakeable.

Henrik is also a very sporting player. On the occasion of his 31st birthday in September 2003, in an SPL fixture against Motherwell at Celtic Park, an overzealous referee booked him for “diving”. It was an absolutely ludicrous decision and seldom do I remember such a storm of booing that resounded round Parkhead that day. There are cheats in the modern game, but Henrik Larsson is not one of them. He does not need to be.

He will always give 100%. He never seems to tire. He is the model professional with his perpetual energy and his shorts that occasionally give the impression of being too big for him. It would be difficult to find a better role model in European football, for he never seems to have lost his zest for the game.

It is profoundly to be hoped that Martin O’Neill does persuade him to stay next season but, in the meantime, let us enjoy him, and who knows what this season might yet bring? Certainly with Larsson at his best and the team playing as well as they did at Celtic Park against Lyon, Anderlecht and Bayern Munich, there seems to be little to fear.

Henrik Larsson – truly one of THE Greats and already a Legend!

LARSSON: THE UNTOLD STORY; I sat Henrik down at eight years of age and told him to forget about becoming a footballer.

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/LARSSON%3a+THE+UNTOLD+STORY%3b+I+sat+Henrik+down+at+eight+years+of+age…-a073506403

Byline: DONNA WHITE, Chief Writer

THE road to fame and success for any genius is inevitably scattered with non-believers.

Like John Lennon’s Aunt Mimi, who told the legendary Beatle: “You might have a guitar, but you’ll never make a living out of it.”

Or the movie producer who screen-tested the great Fred Astaire and wrote: “Can’t act, can’t sing… but he can dance a little.”

Celtic superstar Henrik Larsson has a similar story to tell from his days as a boy growing up in the Swedish city of Helsingborg.

He lived for football. And as other kids talked of being train drivers or firemen when they grew up, his only ambition was to become a professional in his favourite sport.

But he has never forgotten his old teacher, Lise-Lotte Johansson, who told him: “Don’t count on football, Henrik, you won’t make much money from it.”

How wrong can you be. Now, with a salary set to top pounds 40,000 a week and the record-breaking striker poised to become a multi-millionaire, his teacher admits she hasn’t forgotten that conversation, either.

Biting her lip, she smiles sheepishly.

“I just wanted him to be realistic. Not many boys make it to be professional players,” she says.

But there are no hard feelings between the former pupil and his teacher.

When the Sunday Mail reminded Henrik of Lise-Lotte’s warning, he nodded and smiled to himself.

“I remember quite clearly her saying those words,” he laughed.

Her ill-informed advice, to a boy whose talent for the game she could not have known, only makes him feel good about himself for having proved her wrong.

“Of course, I hadn’t seen him play. I’m only glad he chose to ignore me,” says Lise-Lotte.

Like most teachers, she had seen boys such as Henrik come and go – dreamers with no interest in academic life, wasting their opportunities.

She says: “He was only about eight or nine when I taught him mathematics and Swedish.

“I told him not to count on football. It didn’t seem likely that he would make much money from it.”

For Lise-Lotte, it was his distinctive looks which made Henrik stand out from the other children.

“He was a gorgeous boy with curly brown hair. But at the front, one of his curls was white-blonde.

“If it wasn’t for his striking appearance, you might not have noticed him.

“He was so quiet and polite. I think all he wanted to do was blend in with the other boys.”

It was not only the maths teacher who doubted him in those early days.

Henrik – affectionately known as Henke in the city which is proud to have raised him – even doubted himself.

Lise-Lotte has since moved on from Wieselgren school in Helsingborg, but there are still many teachers who remember young Henrik, and confess that, like Lise-Lotte, they never dreamed he would become such a success.

Henrik Edward Larsson was born in 1971, to factory worker Eva Larsson and Francisco Rocha, a sailor from the Cape Verde Islands, off the west coast of Africa.

His parents met when Francisco’s ship put ashore in Helsingborg.

The smitten African seaman got a job in a local factory and the couple settled in the city with Kim, Eva’s son from a previous relationship.

They subsequently had two boys, Henrik and Robert.

Although he is a half-brother, Henrik has referred to Kim as “a full brother in my heart”. Partly because their parents never married – and because they felt it would be easier for their youngsters to be accepted in Sweden – Eva and Francisco decided the boys should take their mother’s surname.

Despite this, Henrik recalls occasionally suffering racial abuse at school. But the feisty youngster would answer taunts of “******” with his fists.

He quickly gained the respect of his tormentors and, with his talents on the football field, he went on to become a popular figure within the school.

Jan Gustavsson, who has been at the school since 1970, taught him German.

He said: “German didn’t hold much interest for him. But, then, even when he was very young all he wanted to be was a professional footballer.

“Of course, we hear kids express impossible ambitions all the time, but I once went to see him play for Hogaborg, the local boys’ club, and I was taken aback at his talent.

“None of us could have known he would make it as big as he did, but I had an idea that Henrik would never give up trying to be a professional footballer.”

In the last five years, the competition for pupils between schools in Sweden has become fierce.

It has prompted Wieselgren to specialise in teaching music and football to its youngsters.

“Schools need to offer something extra to attract the children these days,” says Mr Gustavsson.

“Henrik wasn’t the reason we chose to offer football classes – but I suppose it helps when we tell parents that he attended here.

“Before his football career really took off, he worked at the school’s recreation centre for a while, and we would often have lunch together.

“Even then, he was starting to become a star. But no one really noticed, because he was such a nice, down-to-earth guy.”

Ann Bjorkman, who taught Henrik Swedish for three years, says: “He wasn’t very interested in reading and writing. When he wrote essays for my class, they would often be about his dream of becoming a professional footballer.

“One Sunday, my son was playing football for Hogaborg, and I noticed from the match results over the weekend that Henrik had scored two goals.

“The following morning, I congratulated him in class. He was only 13, and quite literally glowed with pride.

“It was obvious that he was pleased I had noticed.”

Playing for the Hogaborg club proved to be an important rite of passage for Henrik.

He learned the hard way that it was going to take more than talent for him to achieve his dream.

He had started playing with the local boys’ side when he was six, and made his way up from the junior teams to the senior squad.

Always small for his age, he seemed to stop growing at 12, while his fellow players sprouted and towered over him on the field.

He still had his speed, but at 13 Henrik found himself spending most of the season on the bench. His enthusiasm waned, and he seemed to stop trying so hard.

Hogaborg coach Kenneth Karlsson remembers the many pep talks he and another coach, Bengt Persson, had with the young player.

“Henrik didn’t realise that all he needed was a little time to grow, and he would be able to play with the best of them.

“At 13, he was so small and was often made substitute. He was really frustrated about that. But he was not built like a footballer, and his game suffered for a time.”

His self-doubt came at a difficult time, when many of his friends were tiring of football, and quitting – pressurising Henrik to join them.

Kenneth says: “I remember having many chats with him around that time, as did Bengt, who sadly passed away in 1999.

“We saw his skill, so we didn’t want him to quit. We spent a long time with him, discussing his future.”

Also at that time, Henrik’s parents were splitting up. Everything in his life, it seemed, was changing.

Football had been the one constant in his life, but his coaches told him that unless he worked hard, he couldn’t even rely on that to continue. Talent wasn’t enough.

“Once we’d convinced him to continue, Henrik really tried much harder.

“He trained two or three times a day by himself and I don’t remember him missing a single club training session,” recalls Kenneth. As his game started to improve, so, too, did the crowds who came to watch Hogaborg – particularly young girls.

“He got quite a female fan club,” laughs Kenneth.

“Henrik was interested in girls, and they really began to take an interest in him.

“He was the star player. And with his curly hair, the girls really couldn’t get enough of him.He was the rasta man.”

Despite all the attention, football was his only love.

Yet as Henrik turned 19, all that was about to change…

THE MAGNIFICENT 7: THE EARLY YEARS – HEADING FOR THE BIG TIME; Size didn’t matter as tiny Larsson grew into superstar.

Link/Page Citation

Byline: By Gary Ralston

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/THE+MAGNIFICENT+7%3a+THE+EARLY+YEARS+-+HEADING+FOR+THE+BIG+TIME%3b+Size…-a0117101204

THE field of dreams where Henrik Larsson honed his soccer skills has long since been swallowed by developers.

Now, if you look from the eighth floor of the tower block where he grew up,the scrub land where neighbours once watched him play has been replaced by a nursing home.

It seems, on the face of it, a poor memorial to his childhood in Narlunda, a district south of Helsingborgs but once you understand the pride he takes in his community you realise it couldn’t be more fitting.

It was on this piece of land that Larsson and best pal Frederik Bjork, so inspired by the World Cup Final between Argentina and Holland in 1978, ran out to practise their skills with 15 minutes still remaining of the match being shown on television from Buenos Aires.

And a few weeks later he was taking a two-minute walk to the home of Hogaborg BK to kick-start a relationship with his local team, including 14 years as a player, that endures to this day.

General manger Kenneth Karlsson recognised the potential in Larsson froman early age but recalls with a smile the times he and other club officials had to persuade him not to turn his back on the game.

Larsson,who also played floor hockey for IBK Ramlosa in the First Division of the southern Swedish League, was tempted to quit football as a teenager because he was fed up being knocked about.

Talented Karlsson said: ‘At the age of 15 he nearly left us for good to go and play floor ball, a type of indoor hockey.

‘He was tiny and found the physical side of the game very difficult.

‘We sat him down and persuaded him he was very talented. We told him if he worked hard he could have a brilliant future ahead of him in football.

‘Of course, we didn’t know at that time just how brilliant it would turn out to be but it took him a few weeks to be persuaded not to quit.

‘Our club is just a stone’s throw from the apartment block where Henrik was raised and we see at least 600 kids passing through our doors every year to play football, so it was no surprise when he turned up here as a six-year-old.

‘He stayed for 14 years and didn’t leave for Helsingborgs until he was aged 20, which is quite unusual as most of the best players are picked up by the bigger clubs when they are aged 16 or 17.

‘Henrik was not picked up as a result of a lack of talent but, again, because we asked him not to quit.

‘I know the physical side got him down when he was younger but you’ve never seen a guy practice as hard as he did to make the top. Hewas the first player to turn up for practise and always the last to leave and when our team did not train he would turn up and work with the kids.

‘I see the result of it now because he is so strong against opposition defenders and it was no surprise when Helsingborgs showed an interest.

‘However, we persuaded him to hold off for another couple of years as it was better playing senior football for us rather than with the juniors and youths at Helsingborgs and thankfully he agreed.’

Larsson pocketed the princely sum of pounds 300 a month at Helsingborgs and was forced to take a second job but soon quit his post as a fruit packer because he hated it and surprise, surprise took up another post in the community, as a youth worker with kids aged from seven to 16.

Karlsson said: ‘Henrik is honest and never forgets his roots. He always comes back to see us.

‘He has the same friends here now as he did when he first left Sweden. He has not changed he’s still the same guy.Whenever he comes back he often presents prizes to our kids and you should see their faces when he appears it’s sucha thrill for them.

‘Henrik has regularly helped us with equipment for the youth team but the greatest thing he has done is a public relations job for our whole community.’

Larsson, 32, delighted Sweden with his decision to come out of international retirement and play at Euro 2004.

And he has also promised to pull on the Hogaborg shirt again and play for nothing beside kids who idolise him.

Karlsson added: ‘I’m so delighted to see Henrik return and you know how much it means to the country when 150,000 people signed a petition urging him to play again.

‘Everyone is happy and, for us, we’d be glad to see him back playing for us in the summer, although I think it’s more natural for him to return in a couple of years as he still has time left on the international stage.’

So how will the community reward Larsson’s service the Henrik Larsson Stadium has a certain ring to it.

‘Goodness, no!’ laughs Karlsson. ‘Have you seen our ground? It’s quite small and humble there isn’t a stand in it.

‘I think if we were to do something it would be to name a tournament in his honour. The Henrik Larsson Youth Tournament that has quite a ring to it.’

CAPTION(S):

THE MAGNIFICENT 7: 10 – Murdo MacLeod on how Wim Jansen’s bargain swoop of the century stopped ten-in-a-row.

Link/Page Citation

Byline: By Hugh Keevins

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/THE+MAGNIFICENT+7%3a+10+-+Murdo+MacLeod+on+how+Wim+Jansen%27s+bargain…-a0117101226

THE deal that brought Henrik Larsson from Feyenoord to Celtic for just pounds 650,000 in 1997 was the most astute piece of transfer business ever done by any club in Britain.

And that’s according to Murdo MacLeod, one of only three men who really knows what went on behind the scenes when Celtic, then a club in turmoil, decided to make a move for the dreadlocked player who would become their talisman for the next seven years.

Rangers had won nine league titles in a row to equal Celtic’s cherished record from the 60s and 70s.

Tommy Burns had gone from the manager’s office after three years of internal warfare with the club’s obstinate owner, Fergus McCann.

The search for a new manager had centred on trying to persuade Gerard Houllier to take over at Celtic Park. But he had stubbornly refused to put Scotland before the chance to take over at Liverpool.

AndWim Jansen had arrived from a stint in Japan with Hiroshima to the sound of bemused indifference from a Celtic support who wondered what would be next to befall them.

MacLeod and Davie Hay formed the welcoming committee when Jansen met his new players and backroom team for the first time at a pre-season training camp in Holland.MacLeod said:’It was there,onthe first day we had worked together, that Wim sat down with Davie and myself and told us he had a player in mind to start Celtic’s re-building job.His name was Henrik Larsson.

‘My first reaction was to say to Wim, ‘What kind of player is he ?’ Henrik wasn’t well known at that time and my inquiry was a genuine one.

‘Wim just smiled at me,nodded his head and said, ‘He can play all right’.

‘The funny thing is it might have been John Collins who was asked to kick-start Celtic into being a competitive force once again if the move for Larsson had failed.

‘Davie and I both knew what John meant to the Celtic fans and the plan was to approach Monaco for him and then get Paul Lambert, who was at Borussia Dortmund.

‘The intention was that Henrik would be our first signing for the club but then Feyenoord started a court case over the leak of information about the clause in the contract that allowed him to go for a set fee.

‘In the meantime we brought Darren Jackson to the club from Hibs.’

The irony was that the opening day of the new season had Celtic at Easter Road. If the 2-1 defeat they suffered there was hard to take, it was even more painful for Larsson, who came on as a substitute and misplaced the pass that allowed Chic Charnley to score the winning goal.

It would be stretching the imagination to claim that was the first and last error Larsson would ever make on Celtic’s behalf.

But MacLeod had cause to notice that by the end of his first season Larsson had become The Enforcer.

The player who snatched victory from the jaws of defeat with an unerring appreciation of when Celtic were in need of 11th-hour assistance.

MacLeod said: ‘The loss to Hibs was followed by a home defeat to Dunfermline and the rumblings about Wim’s appointment had started.

‘Then we played St Johnstone twice in the space of four days at McDiarmid Park. First in the League Cup when Simon Donnelly’s penalty gave us a win in extra-time and then in the league when Henrik scored a diving header to open the scoring.

‘We went on to win 2-0 and those two games were the turning point.’

Rangers had spent 20 years living with the strain of trying to live down Celtic’s nine-in-a-row success. And MacLeod knew it would be an awesome burden to bear if Rangers created a new championship record that reached into double figures.

He said: ‘I told Henrik he would become a Celtic legend in the space of a single season if he stopped Rangers winning the title.

‘The road to immortality for him started withSt Johnstone and ended with them too.

‘We were at home to Saints on the final day of the season and needed to win to take the championship. Henrik did what he always did and steadied the ship by giving us the lead after only two minutes with an outstanding goal.The rest is history.

‘And yet at the end of that season, Jackie McNamara and Craig Burley took the Player of the Year awards handed out by their fellow players and the football writers.

‘But I knew Henrik’s worth. How many foreign imports could have arrived in anew country with a wife and infant son of just two weeks old and stayed for seven years, while getting better every season ?

‘Henrik managed to pull it off because he has the most professional attitude I have ever come across. The player you see in a match is the same way in training.

‘He has attitude and a will to win that is second to none.

‘There have been no dips in form since he got here, even after coming back from a horrendous leg break against Lyon and surviving an equally distressing jaw fracture in a match with Livingston.

‘Henrik is unique.Even Jimmy Johnstone, the greatest Celtic player of all time, would have no objection to Larsson’s name being mentioned in the same breath as his own.

‘But now the Celtic fans must savour his memory and never say, ‘If only Henrik was here’ next season.

‘A golden era in the club’s history must be allowed to pass with dignity. Celtic will never get anyone like Henrik but they will sign a player whocan score regularly.

‘But he will never be the same as Henrik, whoever he may be.

‘I am proud to call him a friend and we will keep in touch after hehas left this country.

‘I will never forget what he did for Wim andme.Henrik will never let Celtic out of his mind. I’m glad I was present at the marriage made in heaven.’

THE MAGNIFICENT 7: ROTTEN ROTTERDAM – HE’S BEEN TO HELL AND BACK; Ex-Rangers midfield star Giovanni watched pal Henrik suffer at Feyenoord.

Link/Page Citation

Byline: By Colin Duncan

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/THE+MAGNIFICENT+7%3a+ROTTEN+ROTTERDAM+-+HE%27S+BEEN+TO+HELL+AND+BACK%3b…-a0117101217

YOU have to go through the bad to appreciate the good times and, hard though it may be to comprehend, Henrik Larsson’s career has not always been a bed of roses.

The Celtic striker had four seasons at Feyenoord before Wim Jansen secured the deal of the century and brought him to Parkhead for pounds 650,000.

However, Larsson’s spell in Holland was a steep learning curve and his early days with the Rotterdam club were spent mainly on the substitutes’ bench.

Even when Larsson made the breakthrough into the Feyenoord starting line-up he was regularly withdrawn from the action early in the second half.

It was a depressing time for the young Swede, who started to question his own ability and suffered from a major loss of confidence.

Former Rangers star Giovanni van Bronckhorst shared the Feyenoord dressing room with Larsson for three years from 1994 and struck up a close friendship with him which exists to this day.

Van Bronckhorst witnessed Larsson’s troubled period and he admits there were times when he did not look like the player who would later transform himself into arguably one of the greatest ever to wear a Celtic jersey.

The Dutchman said:’Henrik was young when he came to Feyenoord, I think hewas only 21, and he didn’t have a regular starting place. It was difficult for him to try to establish himself.

‘Even once he found his way into the side he was always substituted 25or30minutes from time.

‘You could see he wasn’t enjoying himself and it really affected his game and his confidence.

‘Of course you could still see his talent and his work-rate was excellent back then.

‘But at Feyenoord he didn’t play his best football because maybe he wasn’t enjoying it the way he did at Celtic.

‘His final season in Holland was his best and he scored a few important goals in Europe but I don’t really remember him being a prolific goalscorer.’

Larsson managed just 26 goals from101 starts at Feyenoord aone in four ratio which pales into insignificance alongside his phenomenal record with Celtic.

The Magnificent Seven has scored 242 goals in 315 games since arriving in Scotland and van Bronckhorst is convinced much of his transformation is down to the Celtic supporters, who instantly took Larsson to their hearts.

The Barcelona defender said: ‘Henrik is a player who has to feel at home and he is really adored by the Celtic fans.

‘He really appreciates that and in return it makes him want to play even better to repay their magnificent support.

‘He didn’t have that special relationship in Rotterdam and maybe that’s why he wasn’t as successful ‘I knowhe enjoys life in Scotland and he has responded to the Celtic supporters. He has surpassed all their expectations to establish himself as one of the greatest ever to play for the club.

‘When I joined Rangers in 1998 he had already been in Scotland for ayear.My Rangers team–mates told me he was a good player that season but not really exceptional.

‘However, the following year he started to become stronger, more determined, and he scored a lot of goals.

‘He never looked back after that and whenever Celtic needed him he came up with the goods. It didn’t matter if it was against Partick Thistle or in the Champions League, he would always be there to score the important goals.’

Larsson was a constant thorn in the side of Rangers during van Bronckhorst’s spell in Glasgow although the pair remained the best of friends off the pitch.

The ex-Gers star said: ‘During my time at Ibrox Henrik was the man we always kept an eye on the most. With those kind of players the manager didn’t have to say anything before the game.

‘Everyone knew he was dangerous and we knew if we could stop him from scoring the job would be a lot easier.

‘We managed to keep him quiet ina couple of games but there were a lot of occasions we didn’t.

‘He was Celtic’s talisman and the Celtic team around him became better and better as time went on.

‘If you compare the team from 1998 and the one of the last couple of years there is a huge difference so it’s no wonder nobody can get close to them.’

Larsson has accumulated a host of Player of the Year awards and winner’s medals since coming to Scotland but his most treasured possession is the Golden Shoe he won in season 2000/2001 when he scored an amazing 53 goals.

Van Bronckhorst added: ‘I know his greatest moment was winning the Golden Shoe.

‘It meant a lot to him to be the best in Europe, especially when he was competing against guys like Raul, Thierry Henry and Ruud van Nistelrooy.

‘There is no bigger honour or compliment for a striker because an award like that proves you are the best.’

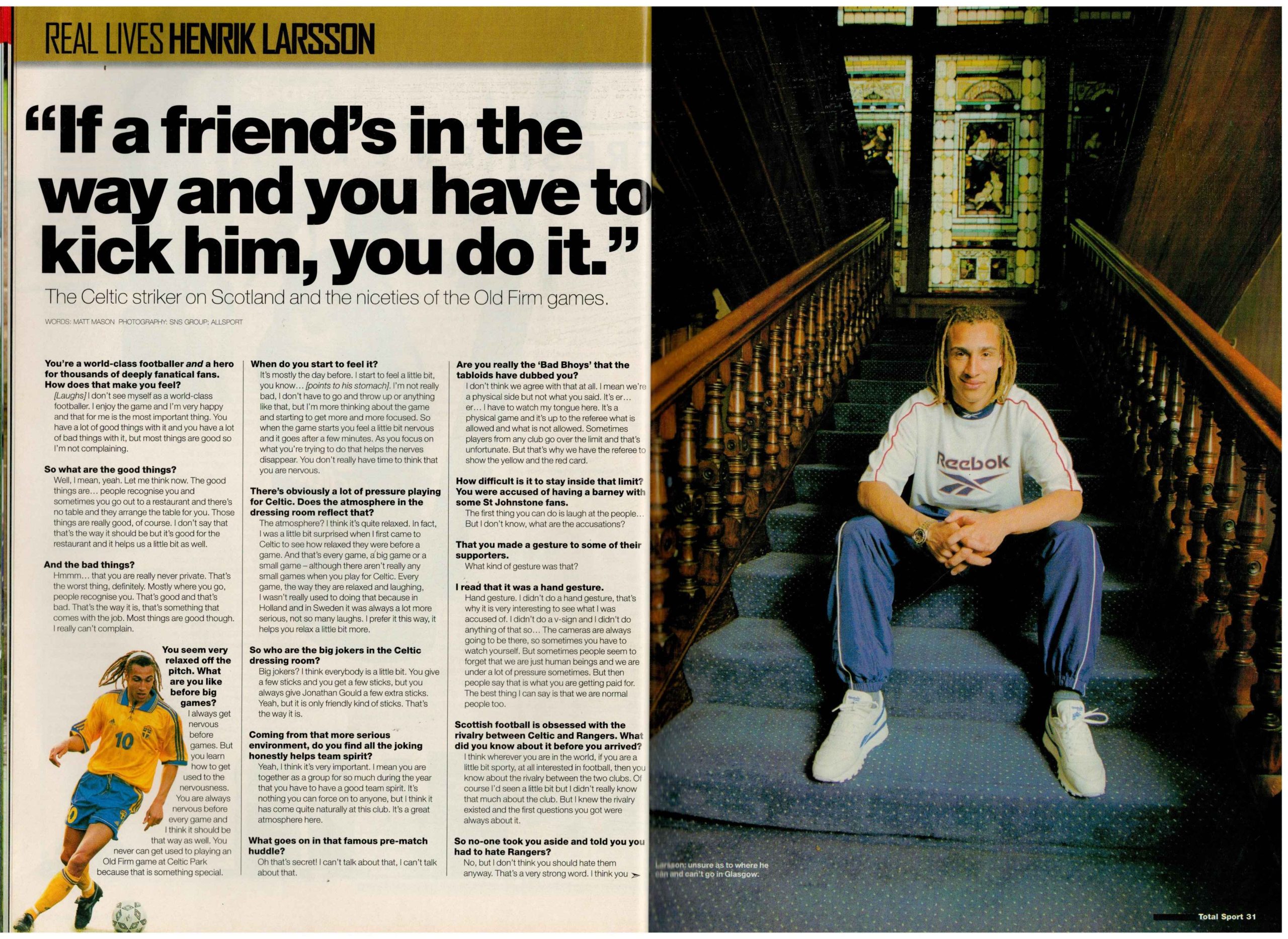

From 1999

Henrik Larsson, Total Sport, Issue 45, September 1999

Martin O’Neill shares what Henrik Larsson privately admitted to him about Celtic and Barcelona

Patrick Sinat

https://tbrfootball.com/martin-oneill-shares-what-henrik-larsson-privately-admitted-to-him-about-celtic-and-barcelona/

Wed 27 December 2023 14:45, UK

Martin O’Neill and Henrik Larsson are two of the biggest Celtic legends of the modern-day era.

Between them both, they helped Celtic through one of the most successful domestic and European periods of their history since the Lisbon Lions.

Winning the first treble in 2001 since the Jock Stein era, O’Neill and Larsson helped end Rangers’ domination of Scottish football to kickstart what we are currently witnessing to this present day.

But there was one trophy that both of these living legends couldn’t get their hands on and it is one that still haunts them to this day. The 2003 UEFA Cup.

Getting to their first major European Final since 1970, Celtic went to Seville that year with great hope that they could lift the UEFA Cup.

With Chris Sutton, Paul Lambert, Neil Lennon and, of course, Larsson in the team, that Celtic side had taken on the might of Liverpool, Blackburn and Stuttgart to get to that final.

Unfortunately, they couldn’t do enough to get past Jose Mourinho’s Porto and despite Larsson bagging a double, Celtic lost the final 3-2 in extra time.

It was a painful end to one of the best memories as a Celtic fan that I can remember and O’Neill has just shared what Larsson would have been willing to sacrifice if it meant that Celtic had won the UEFA Cup in 2003.

O’Neill said [PLZ Soccer], “It was not that long ago that I was speaking to Henrik Larsson and Henrik’s won the Champions League with Barcelona.

“He made a big impact in the game, come on and I was there at the match cheering him on and he said he would have given that up to have won the UEFA Cup with us at Celtic.

“That’s massive.”

That just shows you how much Larsson still holds Celtic dear to his heart. The fact that he would give up the biggest prize in club football to be successful in Europe in the green and white hoops speaks volumes of the player.

It’s why the Celtic fans love him still to this day.

Henrik Larsson: ‘I have 106 caps for Sweden but I see myself as foreign’

Michael Butler

https://www.theguardian.com/football/2024/mar/03/henrik-larsson-i-have-106-caps-for-sweden-but-i-see-myself-as-foreign

Celtic’s ‘King of Kings’ on his tough upbringing, playing with Rooney and Ronaldinho, and falling out of love with the game

@michaelbutler18

Sun 3 Mar 2024 08.00 GMT

Last modified on Sun 3 Mar 2024 08.03 GMT

24

Henrik Larsson is standing in front of the patch of grass where he first learned to kick a ball. Behind him is the block of apartments where he spent his childhood, the balcony from which his mum would call him in for dinner. In front of him are the swings through which he would shoot, and the ponds on top of which he would play ice hockey in the winter.

Närlunda is an estate on the outskirts of Helsingborg, a quiet city near the most southerly tip of Sweden. Närlunda is a complicated place, an idyllic and green high-rise estate by English standards but also the scene of a brutal murder in 2021, where a man was shot dead in a nearby underpass. But then Larsson is a complicated person, devoted to his country but also unsure of his identity.

Benito Carbone poses outside a cafe in Bermondsey

Benito Carbone: ‘I never wanted to leave Wednesday. It was my mistake’

Read more

“I see myself as foreign,” Larsson says, as he looks up at the apartment. “I don’t know what I am, to be honest. I know I have 106 caps for Sweden. I know I’m Swede-ish, yes. But I never felt 100% Swede. I have to respect my father’s [Cape Verde] heritage, so maybe that’s why, but I don’t think I felt Swedish until I succeeded on the football pitch. When you’re nothing, you don’t matter. When you’re something, you’re part of this society. Then people forget where you’re from, what your race is.”

That feeling of otherness – also touched on by Zlatan Ibrahimovic regarding his upbringing in nearby Malmö – lingers for Larsson despite Helsingborg celebrating its most famous son by building a statue of him in 2011 on the city’s coastline.

“There were foreigners living here, coming from Yugoslavia, Greece, Finland. But here in this estate I was the only one with a darker complexion. I had a few fights here. If they call you [the N-word], or something else, I used to hit them. I think that mentality comes from home. You have to stand up for yourself. It wasn’t an easy upbringing. But you have two options: you lay down and cry or you get on with it. I chose the second option.”

At the start of the interview Larsson is interrupted by a phone call regarding his father, who lives nearby (“He’s 92 and has full-blown dementia. I’m a little bit upset with everything”). After Larsson leaves, he phones from the car to say thanks for the coffee. He is calm but confident, vulnerable and articulate, courteous but curt. It is a bewildering mix.

Henrik Larsson playing against Germany at the 2006 World Cup

Henrik Larsson playing against Germany at the 2006 World Cup, one of his 106 caps for the Sweden. Photograph: Tom Jenkins/The Guardian

Without Larsson, Barcelona would surely not have won the 2006 Champions League final, where he came on to provide two assists against Arsenal. Feyenoord and Manchester United fans might wonder what could have been if their clubs had got their hands on the striker in his prime, rather than at the start or end of his career.

But Celtic most defined Larsson’s career; he is their “King of Kings”. In seven glorious seasons in Glasgow, Larsson scored 242 goals in 315 games, including 35 goals in 58 European matches. He is surely the last player to have played in Scotland while regarded as world-class, with Larsson beating Hernán Crespo to the 2001 European Golden Boot after a 53-goal season. Some regard him as the club’s greatest player.

“The players Martin O’Neill brought in helped me become the player I was,” Larsson says. “Chris Sutton, Alan Thompson, John Hartson. We were an excellent team. We beat Blackburn and Liverpool on the way to the Uefa Cup final in 2003, with 16 or 17 internationals in our team. It was a stronger Celtic team than now, and a stronger Rangers team.

Henrik Larsson scores for Celtic against Rangers in 2000.

Larsson scores for Celtic against Rangers in 2000. The Swedish international scored 242 goals in seven seasons for the Glasgow club. Photograph: Richard Sellers/Sportsphoto

“When we played against Rangers, we hated each other. But when it was finished, we were friends. Mostly Rangers fans were no problem. There was once when I was with Giovanni van Bronckhorst [his friend and then Rangers defender], who had just bought a new Porsche. We were in Uddingston because we were picking up some takeaway food. We used to order Chinese food a lot, peking duck after a game. There was this drunk Rangers supporter who wasn’t happy when he saw me and the new car. He was walking towards it, until Giovanni took him away. I loved the rivalry. It took some time to get used to it. I understand what it’s all about now, but not in the beginning.”

Larsson signed in 1997 after a turbulent spell at Feyenoord. He had helped Sweden to third at the 1994 World Cup but Feyenoord did not make the most of his talent, playing him in midfield and sometimes not at all. When the Feyenoord legend Wim Jansen was appointed as Celtic’s manager, he made Larsson his first signing for £650,000. The Swede, with dreadlocks inspired “by Ruud Gullit and Bob Marley”, scored 16 goals to help deny Rangers a 10th consecutive title in 1998.

The beginning of the end at Celtic was that Uefa Cup final, perhaps Larsson’s finest game for the club, in which he netted twice. Celtic were beaten 3-2 in extra time by José Mourinho’s Porto, who won the Champions League the following season. “I still haven’t gotten over that one,” Larsson mutters. “I wish I had done more, because I know how much it meant to the Celtic fans. There were more than 50,000 of them in Seville.”

Larsson informed the club shortly after that the next season would be his last. His teary departure in front of a packed Celtic Park and final interview alongside a crestfallen O’Neill are legendary.

“I don’t often show it but I’m an emotional person,” Larsson says. “I spent seven years at Celtic and if I had walked away without any tears, there would have been something wrong. I didn’t plan to cry but that’s what my heart told me. I didn’t show a lot of emotions otherwise, so I think people were a little shocked.

Henrik Larsson and his Barcelona teammates celebrate after beating Arsenal in the 2006 Champions League final

Larsson and his Barcelona teammates celebrate beating Arsenal in the 2006 Champions League final, in which he provided the assists for both Barça goals. Photograph: Ullstein Bild/Getty Images

“I got about 30 offers after announcing I was leaving Celtic, from Spain, Italy, Germany, France, something from the UAE. I got a phone call from my wife, Magdalena, saying Barcelona was interested. I was in my bubble with Sweden at the 2004 Euros. I said: ‘Tell them they have to wait,’ as I didn’t want to disturb my preparations. She laughed and said: ‘I don’t think they are going to wait.’ So she went straight over to Spain with my agent and took the negotiations herself.

skip past newsletter promotion

Sign up to Football Daily

Free daily newsletter

Kick off your evenings with the Guardian’s take on the world of football

Enter your email address

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

“Obviously it was a very different dressing room to Celtic. Coming to Barcelona, we had Ronaldinho, they also signed Deco, [Ludovic] Giuly, Samuel Eto’o at the same time as me. I enjoyed not being the main man any more. Ronaldinho had the pressure. And he dealt with it completely differently.”

Larsson was loved at Barcelona for his goals and work rate but nearly didn’t make the 2006 Champions League final squad. He and Lionel Messi had hamstring injuries in the buildup. “It was touch and go between me and Messi. But he sat in the stands and I went to the bench. Messi wasn’t the Messi then that he became. He was really, really good but not the player he was a year or two later. But also playing an English team, Frank Rijkaard knew I was used to that physical game.”

On the pitch after, Arsenal’s Thierry Henry was in no doubt who swung the final. “You want to talk about people that make the difference. That was Henrik Larsson, with two assists. I didn’t see no Ronaldinho, no Eto’o.”

Larsson left Barcelona that summer, when he scored against Sven-Göran Eriksson’s England at the World Cup. “He’s the best managerial export we ever had,” Larsson says. “There’s nothing close to Sven. Unfortunately he’s sick of course, but we always had a connection. Helsingborg made a deal in 1989 that our most promising player of the year could go to train with Benfica [where Eriksson was the manager]. I was there for a week and it went quite well. Sven told me that if it wasn’t to do with the restrictions of three foreign players, he would have signed me.”

Henrik Larsson and Wayne Rooney in 2007

Larsson on life at Manchester United; ‘I was living at the Lowry … Louis Saha and Patrice Evra would take me to lunch, Wayne Rooney too. I thought: “Oh, they really care.”’ Photograph: Jon Super/AP

After the 2006 World Cup, and still at the top of his game at 34, Larsson made a shock return to Helsingborg but there was to be a final twist: Manchester United. He was at Old Trafford for only three months but he dazzled his teammates and Sir Alex Ferguson, and vice versa.

“When I joined Manchester United, my brother Kim had a christening for one of his boys,” Larsson says. “I asked Sir Alex if it was possible. He arranged a private jet for me to get home after a game. I was only there for 10 weeks but he made me feel so welcome. I was living at the Lowry [hotel]. Louis Saha and Patrice Evra would take me to lunch, Wayne Rooney too. I thought: ‘Oh, they really care.’ So you want to do good by them. It was an honour to represent Manchester United.”

Larsson, a new grandfather, remains busy with his own clothing line and a golf habit acquired in Scotland. His son, Jordan (named after Michael Jordan), plays professionally for FC Copenhagen after leaving Spartak Moscow just before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. “Jordan had a new-born child with his now wife. They had to leave a lot of things behind. He took one of the last private jets out of Russia. It was just about him getting out.”

Henrik Larsson

‘For me as a professional player, I never cared about money,’ says Larsson. ‘It was about playing football, the love of the game.’ Photograph: Emma Larsson/The Observer

Most recently Larsson Sr worked as a coach under Ronald Koeman at Barcelona but he has fallen out of love with football.

“I’m so tired of the game. I felt that when I was in Barcelona as a coach, but I just wanted to check one more time what I already knew. The demands are so high. It was terrible the way Koeman got sacked, the way we got sacked. I’m tired of the game because more now than ever it’s about the money. I understand I made good money from my career. You can’t compare me with a factory worker. But for me as a professional player, I never cared about money. It was about playing football, the love of the game.

“I had an opportunity to go to Manchester United in the 1990s from Celtic. I would have earned more, maybe £10,000 or £15,000 a week more. But I had just come off three and a half years at Feyenoord where it had been up and down. I had just found my feet [at Celtic] and I wanted to go on with that. We’d played in the Uefa Cup, I played for Sweden, I didn’t feel I needed to go somewhere else. I didn’t become a superstar at Barcelona, I became a superstar at Celtic.”