M | Player Pics | A-Z of Players

Details

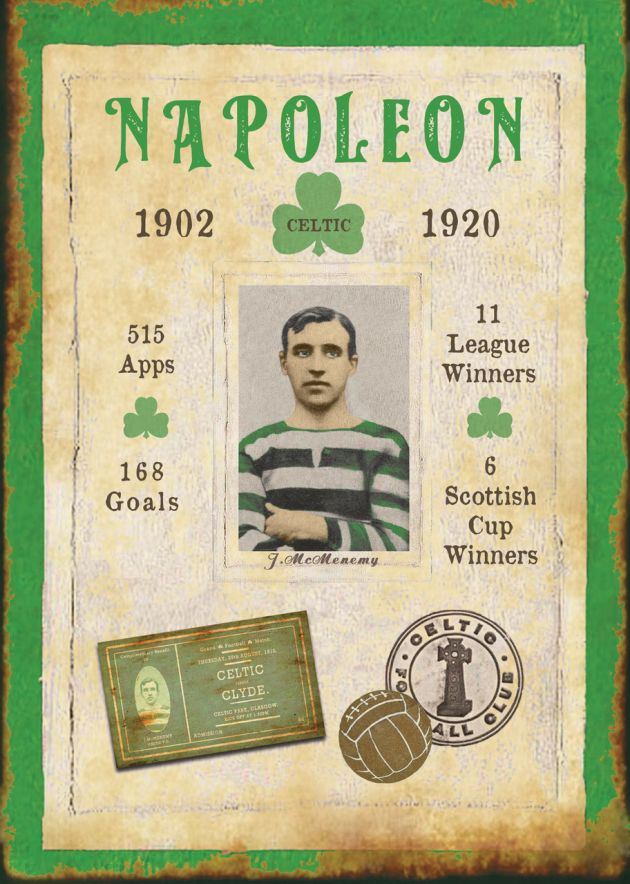

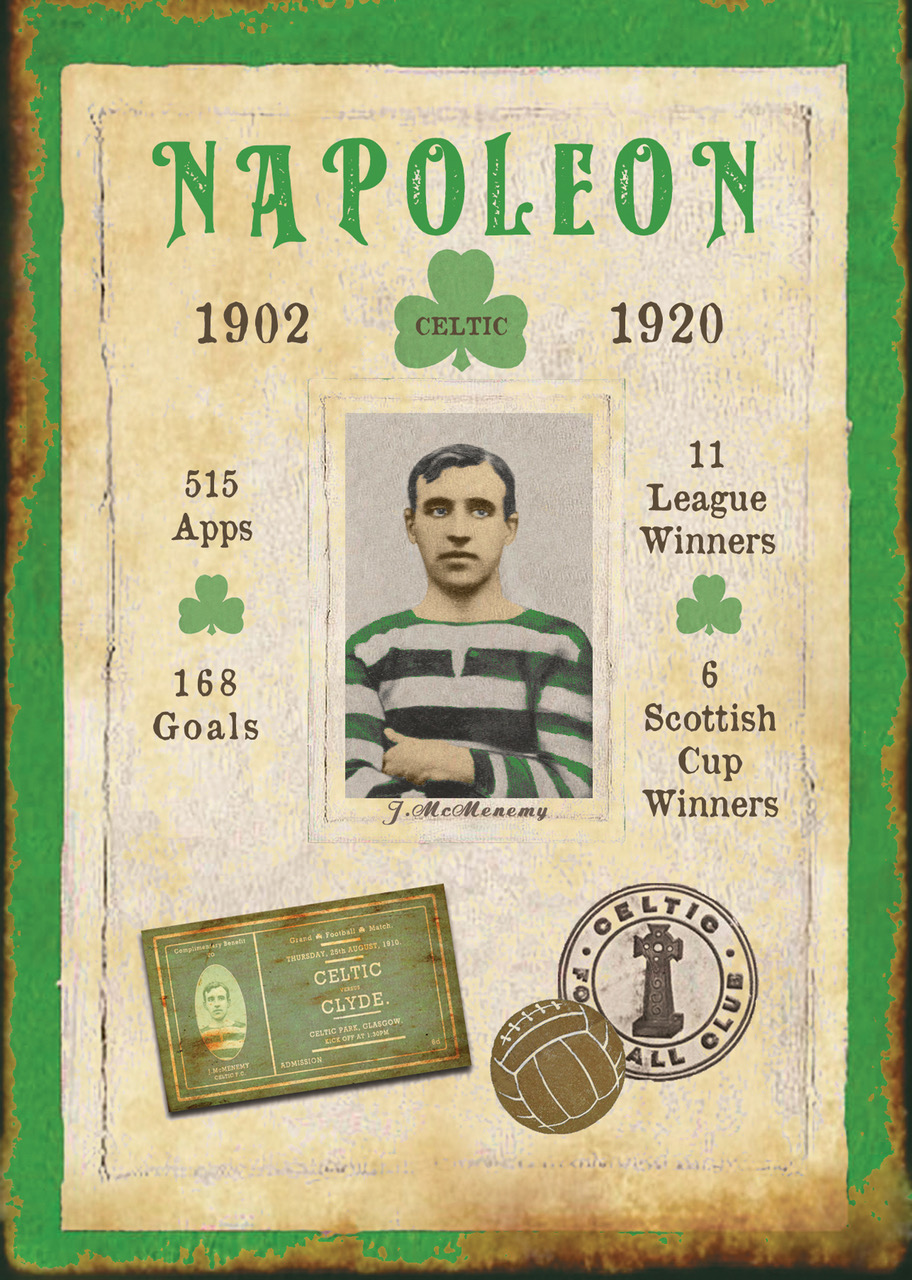

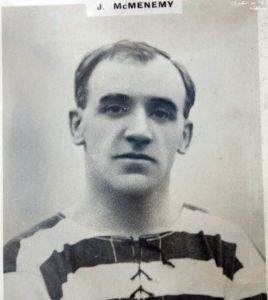

Fullname: James McMenemy

aka: Napoleon, Jimmy McMenemy, James McMenamin, Jimmy McMenamin

Born: 23 Aug 1880

Died: 23 June 1965

Died at: Robroyston Hospital Glasgow (Jimmy’s home at his death was: 249 Whitehill Street Glasgow)

Birthplace: 146 King Street Rutherglen, Scotland (James McMenamin on Birth Certificate)

Signed: 6 June 1902

Left: 20 June 1920

Position: Forward, Inside-left

Debut: Celtic 3-0 Port Glasgow, League, 22 Nov 1902 (scoring once)

Internationals: Scotland

International Caps: 12 Caps

International Goals: 5 Goals

Assistant Manager: 1934-1940

Biog

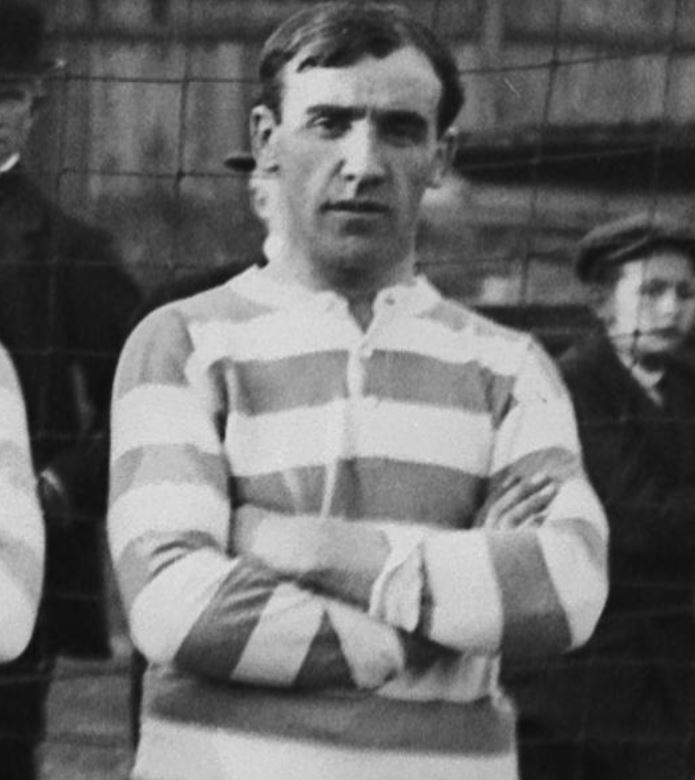

As a Celtic Player

The magnificent Jimmy ‘Napoleon‘ McMenemy ranks among the greatest of Celtic’s figures. The title bestowed on him of ‘Napoleon‘ was an apt epithet of his ability and aura, a commander on the pitch who could outwit his opponents and leave them crushed.

An intelligent and forward thinking player, he was one who really moulded ‘The Celtic Way’ of playing football in first two decades of the twentieth century, a pivotal time in the development of the game.

Signed from Rutherglen Glencairn in June 1902 he made a scoring debut in a 3-0 league victory at Port Glasgow on 22nd November 1902. It was an impressive first outing for the inside-left but few could have guessed that this match was the start of a special relationship which would last for the best part of two decades. His longevity was exceptional, overshadowed only by that of colleagues’ Willie Maley as manager in his 43 year stint and Alec McNair who played even far more matches.

An abundantly talented footballer with the vision and intelligence to dictate a game McMeneny was nicknamed ‘Napoleon‘ and he marshalled the Celtic forward line which bossed Scottish football for a generation. Grand nicknames were not uncommon especially if they were bestowed by Willie Maley.

Quick feet, a good header of the ball and an excellent passer McMenemy was a major player in the Celtic sides which won 11 championships in his time at the club. He possessed an astute tactical awareness which when coupled with his talent with the ball allowed him to control and dictate games. He was also a calm and collected figure, able to keep his head in the heat of the most ferocious battle.

His intelligent scheming led to the downfall of rivals on a weekly basis as Willie Maley’s Celtic developed into an all conquering football superpower. McMenemy’s combination of brain and brawn made him the most formidable of opponent for any defence. This was typified in the match against Rangers on Ne’er day 1914 when McMenemy cleverly dribbled around five men before smashing the ball high into the goal. It was a moment that clearly illustrated his sublime talent. Celtic were to be peerless throughout much of the war, and McMenemy was a great part of that, keeping spirits high on the homefront as was requested by the authorities.

On the pitch, he was not the most vocal but one incident brought out a fine quip from the great man:

The game [Celtic 1-1 Barnsley 3 Sep 1912] was anything but ‘friendly’ with Barnsley from Yorkshire where (where they still boast about breeding them tough with chips on both shoulders) attacking Celtic rather than tackling them in the relentless rain. McMenemy, who normally never said a great deal on the field or afterwards complained to Utley about the constant fouling. Utley said: “In English football, this team of yours wouldn’t last a month”, McMenemy replied by saying “In Scottish football, yours wouldn’t last a match”.

He managed to make a name with Celtic in two different eras, first was the magnificent era in the first decade of the 1900’s which saw Celtic win six league titles in a row, in a side with very fine footballers. Then in the 1910’s again with another great side despite first being thought to be on his way out (he was far from it).

McMenemy left Celtic for a season having retired from the game. Not fully clear why but likely age, wear and tear had taken its toll. Due to his knees and age, rather than join the war he was instead stationed in munitions factories in Ayr and then Glasgow.

Napoleon returned to the Bhoys the next summer to a rapturous welcome from fans and he stayed at Parkhead until June 1920. His motivation had returned and the old ‘knees’ seemed to have recovered. Some may query why he returned, but it’s a wish that most footballers after the end of their careers could only dream about, to have that one more chance.

This was to be a swansong as unlikely there was to be a further opportunity again at his age.

To the pleasant surprise of many, it was to be an Indian Summer for him as one author wrote. Celtic regained some of their old spirit and fought to win the league, something they had monopolised for much of the past twenty years. Great days again. McMenemy was even retitled as being Celtic’s ‘Foch’ in reference to the French military commander, but Napoleon was better as it is more grandiose.

With Celtic he helped them push towards another league title in 1918-19, using his experience and skill to push us all the way against a strong Rangers side. The final season was more difficult and sadly was no success but the support was still glad to have him.The disappointment of the last season saw a clear-out needed and due to his age, it was no surprise to see McMenemy be moved on.

It was all over at Celtic and his departure was another marker noting the end of one of Celtic’s glorious chapters. The club was to then begin a slow decline after his departure (albeit with some brief periods of success), but how could you replace someone like him? While with Celtic he played 515 times and scored 168 goals in winning 11 Championships and 6 Scottish Cups.

For McMenemy, there was one last bit of glory. Having moved to Partick Thistle he continued to play and helped win the club to win the Scottish Cup, defeating Rangers in the final. It was a glorious way to end his playing days (albeit he carried on for a short while longer). The incredible part is that he was now over 40. He had scored for Celtic in 18 consecutive seasons.

One story is that after winning that last Scottish Cup against Rangers in 1921, he asked his wife what should he do with the medal (likely in knowledge it would be his last). Her reply:

“Oh, just chuck it in the drawer with all the others!“.

A marvellous player whom we should all be proud to be able to number as one of our own.

As Celtic Coach & Assistant Manager

During this period, Celtic went through what can be described as Celtic’s last great period for twenty years (even though the success was brief). Possibly it signalled the closing chapter of Celtic’s first 50 years of success, although the club had been underachieving for much of the time since McMenemy had hung up his boots.

Prior to McMenemey’s return, Celtic’s decline was accelerating and needed action taken. The club’s domestic hegemony was long gone. One bright point for Jimmy McMenemy was that one of his sons, John McMenemy, played briefly for Celtic and helped the club to a Scottish Cup title, the seventh in the family. Another son, Harry McMenemy, played for Newcastle Utd.

Willie Maley’s time was nearing the end as a manager but he still stubbornly stuck out despite growing numbers wishing (for the right reasons) that he step down. With age he became more cantankerous and obstinate. Bringing in McMenemy was a masterstroke by the board, his arrival on 15 October 1934 was greeted with great enthusiasm by all at Celtic.

McMenemy was by nature a self-effacing and mild-mannered person, and he carried this over to the coaching side. He was to be the Ying to Willie Maley’s Yang, being more relaxed and approachable for the players to confide in him and even joke with. Results improved from the off, and part of this was his work on improving the team tactics and mentoring young talent (such as the great Jimmy Delaney). His input led to Celtic playing a fast entertaining style that even the difficult Willie Maley was said to warm to it.

Success was paramount, especially as Celtic had not won the league title in around ten years. The challenge was taken up, and under the coaching from McMenemy, Celtic went onto win two leagues titles in 1935/36 and 1937/38 and the Scottish Cup in 1937 (a famous victory over Aberdeen before a record 146,433 fans).

It is probably fair to say that this success at Celtic was far more to do with McMenemy than Willie Maley, and he was the de facto manager. He was to be as important to Celtic as a coach as much as he was a player.

McMenemy was so good as the assistant to Maley that he was even given an assistant himself (Joe Dodds). Possibly this was an early sign that McMenemy was to be made the main manager with Willie Maley to get the message to finally step-down. However, it wasn’t to be. It is argued that McMenemy’s self-effacing and more relaxed manner didn’t fit the then typecast of a manager as straight-laced. Surely his record (as both a player & coach) and his dedication to the club should have been enough? Sadly no, and he was said to not have even been considered, the role passing to Jimmy McStay (admittedly a very worthy candidate himself).

Wartime was to begin in 1939, and Celtic had already begun to slip after the 1937/38 season for various reasons. Jimmy McMenemy cannot be wholly absolved for his part in the slip, however he wasn’t the one making the final decisions. The loss of great players (such as Willie Buchan) with no replacements or fresh blood meant that he cannot be held entirely responsible either (nor should he be).

Despite being kept on once Jimmy McStay took the reins at Celtic, he didn’t stay long and left Celtic in the summer of 1940. It is not known if it was his choice or if he was pushed. We shouldn’t concentrate on this point but rather remember the great memories that he left at Celtic as a coach as much as a player.

Quite simply a Celtic great.

Post-Celtic

Always a great Celt, he stuck firm by the club as a supporter even during the barren years in the late 1950’s/early 1960’s, stating in a speech to a Celtic Supporter’s Association that Celtic would soon be back on winning terms. Celtic were to finally turn things around but that was in 1965 with the momentous Scottish Cup win. It must have been painful for such a great to see the Celtic First Team wait so long before regaining their pride once more.

Sadly, Jimmy McMenemy died very shortly after that victory, passing away in June 1965. That victory was to be a turning point for the club, and he was to miss the golden period for the club under Jock Stein. He would have been so proud to have seen the club that he helped build during its first golden period and buttress during some of its most difficult days, now scale the heights back to the top where it belonged.

Playing Career

| APPEARANCES | LEAGUE | SCOTTISH CUP | LEAGUE CUP | EUROPE | TOTAL |

| 1902-1920 | 456 | 59 | N/A | N/A | 515 |

| Goals: | 144 | 24 | – | – | 168 |

Major Honours WIth Celtic

Scottish League

Scottish Cup

Pictures

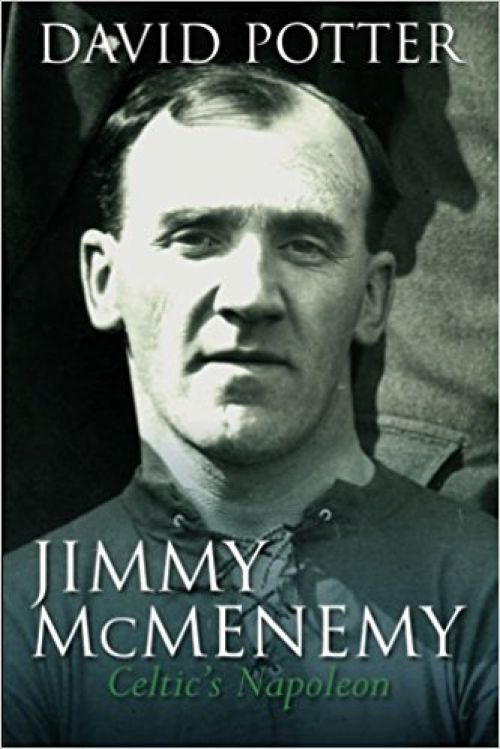

Books

Links

Notes

- *According to Frank Worrall, in his book “Celtic United” (Mainstream Publishing) James McMenemy is the Great uncle of Lawrie McMenemy, manager of 1976 F.A. Cup winning side Southampton and assistant to England manager Graham Taylor 1990-1994.

Articles

JIMMY McMENEMY

by David Potter

Jimmy McMenemy was one of the really great Celtic players. He was born in 1880 and played from 1902 until 1920 at a time when Celtic had two really great teams, 1905-1910 and 1914 – 1917, and when the managerial powers of Willie Maley were at their height. In some ways, McMenemy typified the Celtic of that era – a tricky dribbler, a brilliant passer, a cannonball shot (unusual in such a small and slightly built man) and a great team player with loyalty and level-headedness his hallmarks.

His nickname was Napoleon. It is a curious one when one considers that the original Bonaparte had been the Britain ‘s greatest enemy until the grizzly horrors of the Kaiser and Hitler came along later in the 20 th century. Why would a footballer be named Napoleon? In fact, Jimmy had a certain resemblance to old Boney. He was about the same height and build, but the real answer must lie in his brainpower and his ability to transfer his considerable intellectual capacity to a football field. Napoleon was respected even by his opponents for that. So was Jimmy McMenemy.

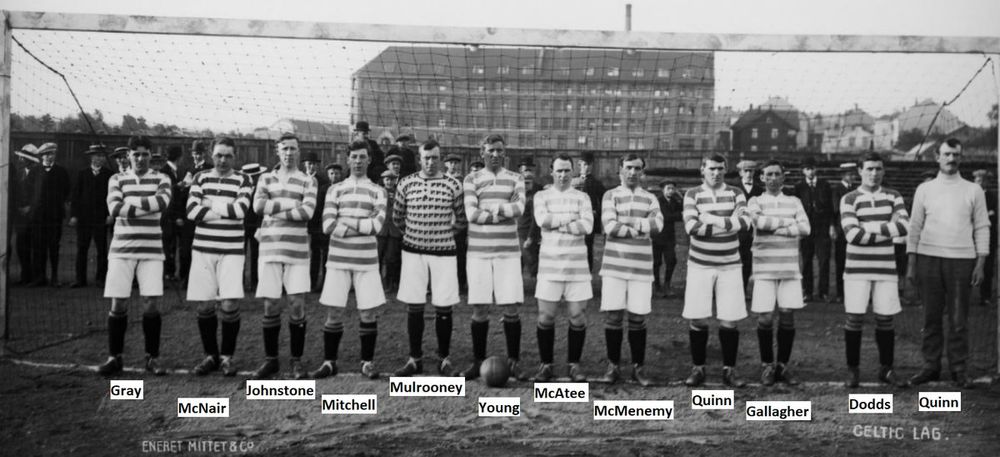

He joined Celtic from Rutherglen Glencairn, signing, legend has it, “up a close in Union Street ”, as Maley began his ingathering of talent. His first season was no great success, but by the end of 1904, the first great Celtic team had taken off, and the forward line of Bennett, McMenemy, Quinn, Somers and Hamilton had no equal in world football. For six years they won the Championship with the crafty McMenemy holding the ball, slowing things down, reading Quinn perfectly for the incisive pass and performing a vital link in the right wing triangle with Sunny Jim and Alec Bennett which exuded excellence.

Even when that great team broke up after 1910, with McMenemy now 30 and entitled to consider that his best years were behind him, Maley had other plans for Napoleon. In December 1911, McMenemy was being challenged for his place by a prodigiously talented Irishman called Patsy Gallacher. Rather than try to bully the spindle shanked, emaciated looking youngster out of the team, McMenemy approached Maley with the suggestion that Gallacher should indeed take his place at inside right while he (McMenemy) would play at inside left. This was a total success and by 1914 another great Celtic team was in place – arguably as good as the one of ten years ago, but destined to be denied by the Kaiser of the chance to prove it.

By this time, McMenemy had played 11 times for Scotland (he would earn another cap after the Great War) and had never been on a losing side. Along with Jimmy Quinn, he played a glorious part in the 1910 2-0 win over England at Hampden, and in 1914 it was he and Willie Reid of Rangers who won the day for Scotland . A week after that game, with McMenemy the hero of the hour, Celtic played Hibs at Ibrox in the Scottish Cup Final and after an ineffective first game, McMenemy and Gallacher destroyed Hibs in the Replay to land the League and Cup double for the third time in his career.

The forward line of McAtee, Gallacher, McColl, McMenemy and Browning would be chanted and repeated frequently in the trenches of Flanders (and possibly even the Post Office of Dublin) in future years. It might even have been the last words that some soldiers said. Some cried for their wives, some their mothers, others for Jimmy McMenemy!

Jimmy himself continued to play during the war years, working in the munitions industry as well, as circumstances demanded. League titles were won in 1915, 1916 and 1917, but there was no Scottish Cup, nor Scotland Internationals. In 1918, he may well have thought about retirement at the age of 38 after the effects of an injury. In addition conscription looked like catching up with him. For some reason, however, his papers never came, and then in November Germany surrendered, thus allowing Napoleon to return to Celtic Park . The crowd rose to welcome him back, and by the end of the 1918-19 season he had won his 11 th League Championship for Celtic, although it must be said that three of them were war-time ones. Although unofficial, they are by necessity demeaned by the unreal circumstances obtaining at the time.

In summer 1920, with his 40 th birthday fast approaching, Maley let Jimmy go, paying full praise to one of his greatest and longest serving players. He was snatched up immediately by Partick Thistle, and astounded the world in April 1921 by helping the Thistle to their one and only Scottish Cup victory. Indeed it was McMenemy’s pass which fed Blair to score the winning goal in the Final. Appropriately, the opponents were Rangers and even more appropriately the venue was Parkhead!

Thus Jimmy won a record seven Scottish Cup medals – 1904, 1907, 1908,1911, 1912, 1914 and now 1921. It could have been more, but he was prevented by the Hampden Riot of 1909 and the five years of the Great War. Billy McNeill would, in later years, equal that record and Bobby Lennox, technically, would beat it, although some of Bobby’s Cup Final medals came via the substitutes’ bench.

Yet Napoleon’s contribution to Celtic was, even then, not finished. In 1934, he was invited back to Parkhead as trainer and de facto Assistant Manager to his old mentor, the ageing and increasingly prickly Willie Maley. Such a move was almost akin to the return of Jock Stein in 1965, in that it really should have happened earlier, but when it did, the results were startling. It was due to McMenemy in no small measure that the great sides of 1936, 1937 and 1938 appeared, with Napoleoen nurturing the precocious young talent of Delaney, Buchan, Murphy and Crum to the glory year of the Empire Exhibition Trophy.

He was dismissed in 1940, but did not take umbrage. He remained a faithful Celt, talking to newspapers and everyone else about their prospects. People would recognise him on a train or in the street, nudge one another and say, “That’s McMenemy!”

He supported Celtic through the awful years of the 1940s and lived long enough to see the Hoops win the Scottish Cup of 1965 when Jock Stein returned. Sadly he died in the summer that year at the age of 85, one of the greatest Celts of all time.

His family kept up the football tradition. His son John won a Scottish Cup medal for Celtic in 1927, Harry played for Newcastle United and of course Laurie McMenemy, the former Manager of Southampton and many other teams, is the great-nephew of Napoleon.

Unlike the French Emperor, there was no Waterloo , no Elba , no St. Helena , no humiliation. His legacy continued and he remains one of the great characters of Celtic history. It is a shame that Rod Steiger could not play Jimmy McMenemy in a film!

‘Let’s talk about Napoleon!’ David Potter

By Editor 18 April, 2019 No Comments

ON 18 April 1908, in a very one-sided Scottish Cup final, Celtic beat St.Mirren 5-1 before 58,000 at Hampden to lift the trophy for the sixth time. Alec Bennet scores two, and Jimmy Quinn, Peter Somers and Davie Hamilton one each, but the best man on the field is Jimmy McMenemy, now called “Napoleon”, the one member of the forward line who did not score a goal!

JIMMY McMENEMY – CELTIC’S NAPOLEON

Jimmy McMenemy was one of the really great Celtic players. He was born in 1880 and played from 1902 until 1920 at a time when Celtic had two really great teams, 1905-1910 and 1914 – 1917, and when the managerial powers of Willie Maley were at their height. In some ways, McMenemy typified the Celtic of that era – a tricky dribbler, a brilliant passer, a cannonball shot (unusual in such a small and slightly built man) and a great team player with loyalty and level-headedness his hallmarks.

His nickname was Napoleon. It is a curious one when one considers that the original Bonaparte had been the Britain’s greatest enemy until the grizzly horrors of the Kaiser and Hitler came along later in the 20th century. Why would a footballer be named Napoleon? In fact, Jimmy had a certain resemblance to old Boney. He was about the same height and build, but the real answer must lie in his brainpower and his ability to transfer his considerable intellectual capacity to a football field. Napoleon was respected even by his opponents for that. So was Jimmy McMenemy.

He joined Celtic from Rutherglen Glencairn, signing, legend has it, “up a close in Union Street”, as Maley began his ingathering of talent. His first season was no great success, but by the end of 1904, the first great Celtic team had taken off, and the forward line of Bennett, McMenemy, Quinn, Somers and Hamilton had no equal in world football. For six years they won the Championship with the crafty McMenemy holding the ball, slowing things down, reading Quinn perfectly for the incisive pass and performing a vital link in the right wing triangle with Sunny Jim and Alec Bennett which exuded excellence.

Even when that great team broke up after 1910, with McMenemy now 30 and entitled to consider that his best years were behind him, Maley had other plans for Napoleon. In December 1911, McMenemy was being challenged for his place by a prodigiously talented Irishman called Patsy Gallacher. Rather than try to bully the spindle shanked, emaciated looking youngster out of the team, McMenemy approached Maley with the suggestion that Gallacher should indeed take his place at inside right while he (McMenemy) would play at inside left. This was a total success and by 1914 another great Celtic team was in place – arguably as good as the one of ten years before, but destined to be denied by the Kaiser of the chance to prove it.

By this time, McMenemy had played 11 times for Scotland (he would earn another cap after the Great War) and had never been on a losing side. Along with Jimmy Quinn, he played a glorious part in the 1910 2-0 win over England at Hampden, and in 1914 it was he and Willie Reid of Rangers who won the day for Scotland. A week after that game, with McMenemy the hero of the hour, Celtic played Hibs at Ibrox in the Scottish Cup Final and after an ineffective first game, McMenemy and Gallacher destroyed Hibs in the Replay to land the League and Cup double for the third time in his career.

The forward line of McAtee, Gallacher, McColl, McMenemy and Browning would be chanted and repeated frequently in the trenches of Flanders (and possibly even the Post Office of Dublin) in future years. It might even have been the last words that some soldiers said. Some cried for their wives, some their mothers, others for Jimmy McMenemy!

Jimmy himself continued to play during the war years, working in the munitions industry as well, as circumstances demanded. League titles were won in 1915, 1916 and 1917, but there was no Scottish Cup, nor Scotland Internationals. In 1918, he may well have thought about retirement at the age of 38 after the effects of an injury. In addition conscription looked like catching up with him. For some reason, however, his papers never came, and then in November Germany surrendered, thus allowing Napoleon to return to Celtic Park. The crowd rose to welcome him back, and by the end of the 1918-19 season he had won his 11th League Championship for Celtic, although it must be said that three of them were war-time ones. Although unofficial, they are by necessity demeaned by the unreal circumstances obtaining at the time.

A copy of The Story of The Celtic by Willie Maley which the club presented to Jimmy, he has signed it too.

In summer 1920, with his 40th birthday fast approaching, Maley let Jimmy go, paying full praise to one of his greatest and longest serving players. He was snatched up immediately by Partick Thistle, and astounded the world in April 1921 by helping the Thistle to their one and only Scottish Cup victory. Indeed it was McMenemy’s pass which fed Blair to score the winning goal in the Final. Appropriately, the opponents were Rangers and even more appropriately the venue was Parkhead!

Thus Jimmy won a record seven Scottish Cup medals – 1904, 1907, 1908,1911, 1912, 1914 and now 1921. It could have been more, but he was prevented by the Hampden Riot of 1909 and the five years of the Great War. Billy McNeill would, in later years, equal that record and Bobby Lennox, technically, would beat it, although some of Bobby’s Cup Final medals came via the substitutes’ bench.

Yet Napoleon’s contribution to Celtic was, even then, not finished. In 1934, he was invited back to Parkhead as trainer and de facto Assistant Manager to his old mentor, the ageing and increasingly prickly Willie Maley. Such a move was almost akin to the return of Jock Stein in 1965, in that it really should have happened earlier, but when it did, the results were startling. It was due to McMenemy in no small measure that the great sides of 1936, 1937 and 1938 appeared, with Napoleoen nurturing the precocious young talent of Delaney, Buchan, Murphy and Crum to the glory year of the Empire Exhibition Trophy.

He was dismissed in 1940, but did not take umbrage. He remained a faithful Celt, talking to newspapers and everyone else about their prospects. People would recognise him on a train or in the street, nudge one another and say, “That’s McMenemy!”

He supported Celtic through the awful years of the 1940s and lived long enough to see the Hoops win the Scottish Cup of 1965 when Jock Stein returned. Sadly he died in the summer that year at the age of 85, one of the greatest Celts of all time.

His family kept up the football tradition. His son John won a Scottish Cup medal for Celtic in 1927, Harry played for Newcastle United and of course Laurie McMenemy, the former Manager of Southampton and many other teams, is the great-nephew of Napoleon.

Unlike the French Emperor, there was no Waterloo, no Elba, no St.Helena, no humiliation. His legacy continued and he remains one of the great characters of Celtic history. It is a shame that Rod Steiger could not play Jimmy McMenemy in a film!

David Potter

Celtic in the Thirties: Unpublished works of David Potter – Jimmy McMenemy

By David Faulds 28 December, 2024 1 Comment

Celtic in the Thirties: Unpublished works of David Potter – Jimmy McMenemy

Celtic’s Napoleon Jimmy McMenemy, image by Celtic Curio for Celtic in the Thirties, available at Celticstarbooks.com

Tonight we continue our series on The Celtic Star where we post unpublished works of David Potter dealing with Celtic heroes from the 1930s…

Celtic’s Napoleon Jimmy McMenemy, image by Celtic Curio for Celtic in the Thirties, available at Celticstarbooks.com

JIMMY MCMENEMY…

Whoever it was who suggested Jimmy McMenemy to come back to Celtic in October 1934 is also the man who won Celtic the Empire Exhibition Trophy. Whether McMenemy was Coach, Assistant Coach, Trainer or whatever, it was he who, in practice if not in theory, privately if not publicly, ran and organised the team in those momentous years of the late 1930s.

The Empire Exhibition Trophy. Photo The Celtic Wiki

Did Maley recommend McMenemy? We shall never know, but we can work a little of what was going on in the mind set of the Directors in 1934. Celtic in 1934 were failing. The few Scottish Cup successes of recent years – including the spectacular one of 1931 – did not really hide the impalatable truth that Rangers had won the Scottish League every year since 1927 apart from 1932 when Motherwell did it. It was now 8 years since Celtic’s last League win in 1926, and there had never before been such a barren spell.

Yet it was difficult to sack Maley. In the first place, this was not an era in which Managers were sacked at the drop of a hat. And moreover, he could not really be described as a total failure in the grand scheme of things. There were factors over which he had no control – economic depression, the tragedies of John Thomson and Peter Scarff, the sometimes frighteningly sudden rise of Rangers (based on naked religious bigotry) under the man called, not without cause, “ruthless Struth”.

But the main factor was that Maley was so well ensconced in his job. He was on good terms with the Directors – although the relationship was fraught on occasions – understood very well the broader picture of the financial side of the club, and remained a committed Celt.

Celtic Trainer Jimmy McMenemy with Abdul Salem

So he would have been difficult to dislodge and the end result and his replacement might well have been something that the Directors did not want. But it was also clear that he needed someone to help him and to support him without challenging him. Jack Qusklay had been a first class trainer but no Coach, and he had now gone in any case. It needed to be someone that Maley got on with – perhaps one of his great players of the past. Sunny Jim would have been ideal, but he had been killed in a motor bicycle accident ten years ago. Patsy Gallacher was too much of a rebel, Jimmy Quinn was a possibility but still (incredibly) too shy and socially inadequate – but there was still the great Jimmy “Napoleon” McMenemy.

McMenemy was still seen around frequently, still mad on football and a keen follower of his family who were currently adding to the family silver – John who had had a brief and not always happy time with Celtic, was now starring with Motherwell and was the proud possessor of a Scottish League medal in 1932, and Harry had won an English Cup medal with Newcastle United in the same year. Besides, in the same way that he was a very intelligent man on the playing field, he was also far from thick off it. He was also quiet, modest and humble.

Jimmy McStay with some Celtic teammates

Peter Wilson, John Thomson, Jimmy McStay, Jimmy McMenemy, Willie McStay, A Thomson, Jimmy McGrory. Photo The Celtic Wiki

In a word, he appreciated the situation. He had always been a favourite of Maley (and he had put up with Maley for 20 years!) and it was he who was accredited with his suggestion to Maley in 1912 which involved himself moving to inside left and thus allowing the prodigiously talented Patsy Gallacher to come in at inside right. The League and Cup double of 1914, and the consistently fine side of World War One had been built on that idea.

He was by nature a self-effacing man. He knew how good he was, but he never pushed himself forward for anything, always content to stay in the background and always being very supportive of others, constantly singing the praises of Gallacher, Somers, Quinn and Loney while others of course knew that he, Jimmy McMenemy, was as good as any of them.

McMenemy would be very careful now to make sure that Maley was still the Manager and still seeming to run the team. Under the guise of keeping him informed about injuries, he would make a few tactful suggestions about who should play on Saturday etc. but Willie Maley was still the manager. Basically, Maley got on with McMenemy, and McMenemy got on with Maley.

Maley, for his part, also read the situation well. He could be brusque, awkward and cantankerous with most people, not least the Directors, and certainly with opinionated or uppity players. He could put most people in their place, but like all clever dictators, he knew that there are some people whom it does not do to upset. Members of the Press were in that bracket – he knew to keep them on side – and Jimmy McMenemy was another. No doubt, Napoleon would occasionally get his nose bitten off if he caught him at the wrong time, but there were be no lasting offence.

And what a knowledge of football McMenemy brought with him! He had of course been part of the greatest football team there had even been, and one cannot be beside so much talent (as well as allowing for his own ability, of course) without picking up a certain knowledge of the game! He had won the Scottish League six years in a row, and after a brief pause, four years in a row, and then in yet another remarkable season of 1918/19 he had recovered from Spanish flu (from which he very nearly died in November 1918 a week after the armistice) to come back and take the team to yet another League title!

He won the Scottish Cup in 1904, 1907, 1908, 1911, 1912 and 1914 and then at the end of his career won yet another with Partick Thistle in 1921, beating, of all people, Rangers at Parkhead! And that is before we talk about the Glasgow Cup, the Glasgow Charity Cup and the mighty goal that he scored for Scotland against England in 1914 – a story that got a good airing on many a winter’s night in a freezing trench in the next few years.

David Potter’s book on Jimmy McMenemy

So, he was a magnificent player. But we all know, don’t we, that magnificent players are not always great coaches. Jimmy McGrory springs to mind. And often great coaches/managers weren’t always brilliant players – Jock Stein, Sir Alex Ferguson (and dare one include Walter Smith in that category?), but McMenemy was both. Maley had once said that to Napoleon, the football field was like a chess board. In some ways, it was a strange analogy, but he meant that McMenemy could always see that one action led to another. This was perhaps why he was called “Napoleon”.

There was one way in which Napoleon made an instant difference. The forward line of Delaney, Buchan, McGrory, Crum and Murphy was not as good as Bennett, McMenemy, Quinn, Somers and Hamilton nor McAtee, Gallacher, McColl, McMenemy and Browning – but the potential was there. McMenemy remembered that one of the key things about the great forward lines in which he played was that they could interchange position. They were all well-trained – and that was certainly his job now – and could move about at speed dragging their defenders this way and that and wreaking general enthusiasm.

Jimmy Napoleon McMenemy’s Celtic debut. Photo The Celtic Wiki

He knew that full backs were often described as “rugged”. It was a common enough term, and was a euphemism, along like other words like “robust” and “doughty”, for being hard tacklers who were not too particular about injuring opponents. But if there were any things that this breed of full backs and centre halves were not, such things were “speedy”, “mobile” and “adaptable”. It followed then that the wingers had to be fast, and if they could play on the other wing occasionally, then so much the better.

McMenemy was in luck. Jimmy Delaney arrived at about the same time as he did, and Frank Murphy who had been around for a year or two without impressing, suddenly came good under McMenemy. These two had the speed of greyhounds. Delaney was once bizarrely described as having the speed of “the fire brigade”, but there was more to him than that.

He was able to cut inside with the ball at his feet pulling a man with him, and when that happened Murphy could sprint across to the other wing, again with his marker on his heels, and the defence was so dis- orientated that McGrory could find space to await the final ball.

Jimmy “Napoleon” McMenemy. Photo The Celtic Wiki

1935/36 was the season of course in which the Scottish League at last returned, and Jimmy McGrory scored his famous 50 goals. Pictures were taken naturally enough with McMenemy and Maley sitting at either end of the front row. The headgear is significant. Maley has taken off his homburg hat, the better for the cameraman to see his face. He is unsmiling but clearly proud of his team who have now won their 18th League title and at the other side, sits McMenemy, well dressed with his suit and his bonnet. It would have been the way that he dressed on a Sunday, one imagines.

He was not the first Celtic man to be described as “just an ordinary man”. It was famously said about Jimmy Quinn by people who always assumed he was extraordinary until they saw him in ordinary clothes at a railway station, for example. Napoleon would walk around the streets of Glasgow, nodding to people, making a comment about the weather, talking to a child and not everyone would immediately know who he was. Famously, when he had won his Scottish Cup medal with Partick Thistle, he was asked what he wanted done with it “Ach, just pit it the box wi’ the ither wans!”

After a year or two, he had done enough to earn himself an Assistant Trainer. It could hardly have been a better choice. It was Joe Dodds, McMenemy’s old friend. They went back a long way, Jimmy having been the best man at Joe’s wedding and both, by a macabre coincidence having lost a brother at the Battle of Loos in 1915, but both having been persuaded by Maley to play in the Glasgow Cup final of October 1915 which Celtic won, beating Rangers 2-1.

Jimmy Napoleon McMenemy. Photo The Celtic Wiki

There is another famous photograph of Jimmy taken after the end of the Scottish Cup final of 1937. Seagulls are hovering over the now deserted Celtic End and the two goal scorers Willie Buchan and Johnny Crum are holding the Cup. Maley is almost breaking into a smile, Jimmy Quinn in the middle is clearly not smiling – but then he never did – but McMenemy at the end of grinning like a Cheshire cat.

It would be interesting to know if Jimmy McMenemy played any part in the interesting decision to allow Willie Buchan to go to Blackpool in November 1937. It was controversial at the time, but it earned Celtic some £10,000 and Celtic had an immediate replacement in Malky MacDonald. One suspects that Maley had at least talked to McMenemy about it.

It was certainly, in the long term, the right decision, for MacDonald was a great player, and certainly spoke highly of what he had learned from Napoleon.

Maley eventually parted company with Celtic in 1940. McMenemy would have been 60 in that year, otherwise he might have been considered for the job as his successor. In the event, the Directors went for Jimmy McStay, and for one reason or another, McMenemy quietly disappears from the scene.

He lived for another 25 years, eventually passing away in summer 1965 after Celtic had begun to return to greatness under Jock Stein. He was well-known and well-loved at Celtic Park, being allowed, for example, along with his old friend Davie McLean to join the party in the Hampden dressing room after the 7-1 win over Rangers in October 1957. He was a frequent attender at Parkhead, although the dignity of old age meant that he was now wearing a soft hat rather than a bonnet.

There was one rather remarkable reunion. In October 1963 in one of Celtic’s first ever forays into Europe, they were drawn against Basle of Switzerland in the European Cup Winners Cup. They had actually played this team before on May 27 1911 when Celtic on tour had won 5-1. One of the Basle players that night, one Ernst Kaltenbach, heard that Jimmy McMenemy was still alive and flew to Glasgow with the Basle team in order to meet McMenemy again.

They duly met, and watched the game together. It was a night of absolutely foul weather and Celtic won easily 5-0. McMenemy joked that if Ernst had been playing, he would have scored a consolation for Basle.

Jimmy died in Robroyston Hospital at the age of 85. He was described as a Wine and Spirit Merchant and is listed under his real name which was James McMenamin. He died of chronic bronchitis and a cardio-vascular accident, and he seems to have been ill for some time. A strong case can be made out for, given his playing career and then his coaching commitment, that Jimmy Napoleon McMenemy was one of the greatest Celts of all time, if not the actual greatest.

David Potter