A-Z of Players | A-Z of Player Pics | Playing Legends

Details

Name: Quality Street Gang

Ref: The incredible set of youth players at Celtic in late 1960’s/ early 1970s

Time: late 1960’s/ early 1970’s

Blessed talents

The Quality Street Gang was the name given to the prodigious Celtic reserve team of young players in the late 1960’s/early1970’s which Jock Stein nurtured and ultimately brought through successfully to replace the Lisbon Lions as the Celtic first team.

Jock Stein had foresight and wisdom, and the Lisbon Lions were not to last forever (obviously) so with some planning Jock had the blueprint already for the next generation of players.

- David Cattanach

- George Connelly,

- Kenny Dalglish,

- Vic Davidson

- John Gorman

- Davie Hay,

- Lou Macari,

- Pat McCluskey

- Danny McGrain,

- Brian McLaughlin

- Jimmy Quinn (grandson of the legendary Jimmy “Mighty” Quinn)

- Paul Wilson.

Under the shrewd (to say the least) management of Jock Stein these players carried on where the Lions left off and saw Celtic through to the nine league championships in a row.

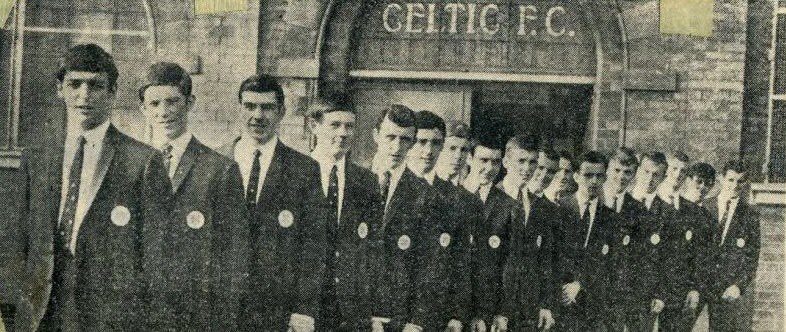

The group of youngsters had been cropped from around 1967, and the prodigious talents played together as a unit from early on including at a youth tournament in Casle Montferranto (Italy) (picture above of the squad).

They were a close unit, and the core of the the “Quality Street Gang” began initially with Connelly, Cattanach and Hay. As the gang grew, their bonds grew, and they not only trained together but fought and socialised together. A major event for all was the regular meet-up at David Cattanach’s home after matches. In the early days, at Davie’s home, many players from the “Quality Street Gang” plus others used to meet up and stay with him for a get together and have a friendly (and competitive) kick about.

The players lining up for these games were astonishing (Hay, Macari, Connelly, Gorman, Dalglish, McGrain, Alex Smith etc). Players from other clubs also used to take part as well at times despite it being centred around the Celtic circle of players. It became such a major part of their lives that those who couldn’t make it any weekend used to ask their team mates for the score from these games the following Monday. It was something special and a whole life in itself. It played a strong part in the development of all those players, and it was all in a back garden!

The list of players and their success was exceptional, not least that of McGrain and Dalglish. Others were not far behind them in some ways, like Macari and Hay. It’s probably the greatest set of youngsters that have ever been nurtured together in British football. Celtic enjoyed great success with these men over coming seasons, and many wonderful stories too, and it was a blessing for anyone to have seen them in action.

So what exactly happened at the end of it all? For Celtic it never reached the heights that the Lisbon Lions had achieved and they should have. The main crux and problem was financial. Times were changing in Scottish football and society. Celtic were no longer sleeping giants and so could not hold back in being compared to just their Scottish counterparts. That’s good recognition for the club, but what goes with that is the other aspects of international comparison, and the biggest comparison for the players is financial. Those players who met up with fellows Scots in the international scene were seeing their counterparts (many a time of lesser ability) raking it in comparatively.

People must realise that the Celtic players at that time were actually not highly paid like modern players (earning not much more than the average joe), and the UK economy was in a declining state. Those with families needed finances to pay for mortgages etc and when the offers were there in England, then it was not surprising that they would be tempted. Celtic is where they wanted to be, but the board was run exceptionally incompetently by Bob Kelly and subsequently Desmond White, neither of whom had any great management ability. Celtic was run with a “Biscuit Tin” mentality (actually the money was held in shoe boxes!), and the finances that could have been raised to support the players were not there. Must be added that Jock Stein & Sean Fallon themselves were poorly paid, and when you reflect on the circumstances, it was not about greed for most but a battle by the players for a decent wage in a short career that could end very quickly.

The players were likely reflecting what was happening elsewhere in the country. Workplace strife was everywhere, and every firm saw management v staff battles. The problems at Celtic could easily have been managed, but sadly they mirrored the economy as a whole.

Finances undermined the club, and lost time and effort that could have been spent on other issues. Davie Hay went on strike over wages at one point before leaving (pushed out) and Lou Macari chased the money to Manchester Utd. Dalglish had been very loyal but eventually left for Liverpool for the challenge (and money). Jock Stein could not handle the financial issues as it was all out of his hands and he was from an old school mentality despite being a moderniser, but he was left with an archaic set-up by the board with little room to manoeuvre. His dreams and achievements with these youngsters were being undone.

Others from the group, did fine but were not of the same ability as McGrain and Dalglish. Davie Cattanach and Jimmy Quinn had their opportunities but couldn’t capitalise on them enough, whilst Brian McLaughlin was undone by a serious injury barring which there was no doubt he would have become a Celtic Great.

The greatest of them all for Celtic was Danny McGrain. He had to battle his own issues (e.g. diagnosed diabetes and later a major injury) but he was world class and lasted the longest at Celtic. He was a gem of a player and was so adored by the Celtic support that it’s hard to even conceive of him to ever play for someone else.

The great irony is that the players who were meant to take over from the Lisbon Lions in the most part left Celtic before even some of the Lions did. Lennox, Jinky and McNeill lasted a long time (Lennox until the 1980s).

The old board had much to answer for, and sadly Jock Stein was left to deal with it all and it possibly lost Celtic the ability to win more European Cups. Celtic had the talent at the club to do so, and that’s the truth. It became a case of what could have been.

Celtic still achieved so much with this group of players: league titles, cup wins, another European Cup final and semi-finals, stuff that memories which live long in the memory are made of. Great victories v Rangers and many special victories over other sides both at home and abroad (e.g. demolishing Hibs in a Cup Final) more than hold their own against anything else in the club’s history.

We’re proud of the players, but we just wish the old board were as appreciative of them at the time as the Celtic support were, and then the club could have held onto them and built upon their ability.

Books

Quotes

“I remember playing in a reserve league cup section with Rangers in it. By the last section game we had to beat Partick Thistle by eight goals to qualify and put Rangers out. Big Jock came into the dressing room and offered us £20 a head if we did it. That was some money for a reserve team bonus and we were all peeing with excitement before we went out to play. I remember Kenny (Dalglish) making a bee-line for the toilet and shouting “Come on, we’ve got to f****** win this!!” By full time we’d won 12-1 and Big Jock paid out. I think that’s when he realised how good we were.”

Lou Macari on the old Quality Street group of players in the early 70s (1995)

Interviewer: “Were you ever intimidated when you walked into a dressing room occupied by such household names?”

Danny McGrain: “No, because when we first arrived we trained together. We were one squad. It wasn’t a first-team squad and reserve squad, so we got to know each other. We would play games together. You would be playing alongside and against the likes of wee Jimmy, Bobby, Big Billy and Bertie. You can’t become friends as we were too young but you just to know them, so when you made your first-team debut it was still a daunting task but you weren’t as nervous. They were still the Lisbon Lions, you still had a great respect for them, and I have great deal to thank them for. For me, Kenny, Victor and Paul to be able to play with these guys was like being at Yale University for football. We had to take everything from it, and I thing we did that.”

Interviewer: “What it was like being part of such a talented group of young players at the club?”

Danny McGrain: “I think Jock Stein and Sean Fallon gave everyone the confidence that they could make it. The whole Lisbon team were ahead of us and it might be another five years before I could even try and get into the first-team. Originally, I was a midfielder who would run about everywhere, and Mr Stein and Sean Fallon put players in various positions in the reserve team – I think I played every position apart from centre forward and centre-half. After two or three years, Mr Stein thought I would be a full-back. However, I never thought I could be a full-back as I always thought that full-backs had to be hard tacklers and good defenders but once I played there I was comfortable. At that time, I was playing with Kenny, Vic Davidson, Lou Macari and Paul Wilson – all guys who made it into the first-team. And because we all made it into the first-team, it made it a bit easier to come into. Because we had come through together, you knew what kind of passes they wanted and what they liked.”

Interviewer: “Was it a good grounding to play in that reserve set-up before you went into the first-team?”

Danny McGrain: “Charlie Gallagher played alongside us a lot and he was a very good player. You learned from him and there would be others who would play when they were coming back from injury. Davie Cattanach was there most of the time as well and he was a rough and ready defender who was very enthusiastic. It was good for us to see someone who was perhaps out the picture but still had great enthusiasm for the club and still worked hard. He also takes a bit of credit for our knowledge of the game.”

Danny McGrain Interview 2012 with Celticfc.net

“I was proud just to be a Celtic player but in that particular era, when the team won the European Cup in Lisbon, we trained with them every day,” he said. “They helped us develop as players along with the manager, Jock Stein, and it was just a marvellous group of young players. We played together in the reserves, developed a strong bond and then we were fortunate, the bulk of us, to make it into the first-team.

“I always enjoyed the Rangers games because invariably we would beat them. We knew what it meant to the supporters, but we knew what it meant to ourselves, there was no better feeling than beating them.

“There were other games, European games that were special. There were the two games against Leeds United, particularly at Hampden, but the biggest disappointment in my life was when we lost the European Cup final to Feyenoord. Our problem was we thought we were going to beat them before a ball was kicked and unfortunately that wasn’t the case.”

Davie Hay (2013)

“At the time it was very nerve-wracking. I remember training at Celtic Park and we would do a warm up of four laps around the pitch.

“I would be at the back with Kenny Dalglish, I was about 17-years old and he was 18. Big Billy McNeill was at the front and we were talking to each other, whispering, “That´s Billy McNeill up there!” After watching the European Cup, and having been part-time for a year, we were now on the park, running around the track with that squad.

“Everyone trained together, wee Jimmy was there, everyone. And after the first lap I thought I was going to wake up, it was so surreal. The players took us into their fold, wrapped a big blanket around us and looked after us for the next two or three years.”

Danny McGrain (2013)

The 1968 picture

The 1968 picture

The Celtic team flew from Glasgow airport on Friday 31st May 1968 to compete in the under-21 tournament, ‘Europeo Juniores Di Calcia Caligaris Torneo XII’. They returned undefeated.

The full line up from this photo in Casale Monferrato, Italy is as follows:

Back Row (Left to Right) – Jackie Clarke (trialist on this tour and signed for two seasons on the back of it), John Gorman, Bobby Wraith, Billy Murdoch and Paul Wilson.

Front Row (Left to Right) – Lou Macari, Danny McGrain, George Connelly (Captain), Davie Hay, John Murray (Vice Captain) and Hugh (Aidan) McKellar.

Squad players who made the trip but who are not in the photo are Tommy Livingstone, Fred Pethard, Kenny Dalglish, Tony McBride, Pat McMahon, Johnny Hemphill, Jim Clark and Victor Davidson.

(Info from Paul John Dykes from his 2013 book, ‘The Quality Street Gang’)

A Celtic select line up to take on Newtongrange Star in 1969.

From the 2013 Book launch, a reunion of QSG members

Left to right:

Denis Connaghan, David Cattanach, Donald Watt, Paul John Dykes (book author), Frank Welsh, Tony McBride,

Hugh ‘Adie’ McKellar, John Murray, Ward White, Jim Clarke, Billy Murdoch, John Taggart, Bobby Wraith,

Paul Wilson, Ray Franchetti and Stevie Hancock (out of picture).

The Quality Street Gang, the last hurrah of Celtic’s golden age

http://www.worldsoccer.com/blogs/celtic-quality-street-gang

World Soccer

March 29, 2014

0 Comments

The Quality Street Gang were expected to supplant the Lisbon Lions as the next great Celtic side, but the new generation didn’t quite live up to the hype.

Kenny Dalglish

Kenny Dalglish in action for Celtic against Atletico Madrid during the 1973-74 European Cup semi-final.

As the ink dried on his Anfield contract in August 1977 and another record-breaking cheque was inevitably cashed by the Parkhead powerbrokers, the departure of Kenny Dalglish signalled the end of a golden era at Celtic Park.

Only ten years earlier, his green and white hooped predecessors had blazed a trail around Europe, bringing the ‘Big Cup’ home to British shores for the first time after a spectacular, quintessentially underdog victory against the mighty Internazionale of Milan. In just two years, Jock Stein had worked his own brand of sorcery on this hitherto unspectacular group of footballers and crafted them into the champions of Europe with only the minimum of domestic acquisitions. But as he stood at the pinnacle of European football, Stein already had designs on Celtic’s next generation of home-grown talent.

Milan’s glitterati had grown old and Stein’s Celtic had knocked the twice World Club Champions off their pedestal in breathtaking fashion. These eleven Scottish individuals, who would be known ad infinitum by the moniker of The Lisbon Lions, had certainly served Stein well and he was not about to let them go the same way as Helenio Herrera’s ‘La Grande Inter’.

How do you replace such an iconic captain and leader of men as Billy McNeill, who possessed all the natural qualities of a born winner? Or a winger of such supreme individual talent and panache as Jimmy Johnstone, whose strength and mesmerising dribbling ability bamboozled defences all over the world? Or the commanding and peerlessly influential and talismanic Bobby Murdoch, who could pass the ball with a range and precision that could orchestrate an entire match? These were just some of the dilemmas that faced Jock Stein but the breaking up of this incredible Lisbon Lions dynasty was made a lot smoother by the sheer raft of talent that were waiting in the wings.

Despite the phenomenal success of his team over the previous few seasons, Jock Stein had possessed the foresight to plan ahead and had signed a procession of prodigious Scottish talents, who had been learning their trade from the very best in European football on the Barrowfield training ground every day since their arrival at the club. Inconspicuous young men whose indoctrination into the Celtic way had been gradual and methodical. These young cubs were reared to replace the Lisbon Lions, the most celebrated football team in the history of the Scottish game.

Jock Stein almost simultaneously crafted two football teams in the late sixties and early seventies, that would ensure Celtic could enjoy utter dominance of the Scottish game for virtually a decade. His young collection of reserve team players would experience many talents, triumphs and tragedies throughout the most successful period in the history of Celtic Football Club and he believed they were so capable that he made a proposal to install them into the Scottish Second Division in 1968. Many clubs feared that they would win the league. The Scottish press christened the Lisbon Lions‘ heir apparent, ‘The Quality Street Gang’ and tales of the precocious second string’s successes have become the stuff of Celtic folklore.

During one almost mythical encounter with Partick Thistle in August 1968, and with Celtic needing at least seven goals to win their Reserve League Cup section over Rangers, they ran out 12-0 winners with Lou Macari scoring four goals.

Two months later Scotland’s national team boss, Bobby Brown, asked Jock Stein to supply him with opposition for a warm-up practice match. Stein sent him the Quality Street Gang and the kids destroyed a full Scottish International team, featuring Ronnie Simpson, Colin Stein, Eddie Gray and Billy Bremner, 5-2. Scotland defeated Denmark nine days later.

The 1969-70 Glasgow Cup Final was still a prestigious enough tournament to attract a near 60,000 crowd on a Monday evening and Jock Stein again took the opportunity to showcase some of his finest protégés. A George Connelly-inspired Celtic, with six Quality Street Kids in the line-up, swept a full-strength Rangers team aside and ran out 3-1 winners.

By the time of the 1970 European Cup final, some of the Gang had already forced their way into this great Celtic side and within a few more years many more would become household names. Indeed, many observers believed that the omission of George Connelly from Stein’s San Siro starting line-up had a major bearing on the outcome of Celtic’s second European Cup final in just three years.

The Quality Street Kids were the highest scorers in British football in season 1970-71 and Kenny Dalglish, who hadn‘t yet made his mark on the first team, scored an astonishing sixteen goals in just six games as the reserves wrapped up a League, League Cup and Second XI Cup treble. Their closest rivals, Rangers were defeated three times in just eight days in the League and two-legged League Cup Final. The scores read: 7-1, 4-1 and 6-1.

Kenny Dalglish had scored 43 goals in two seasons with the reserves but his exploits were being monumentally eclipsed by Lou Macari, who netted 91, and the highly-rated Vic Davidson, who scored an emphatic 92. Both Macari and Davidson’s totals also included a spattering of first team goals.

Celtic’s stylish babes were destroying all reserve competition before them and although Jock Stein’s vision of them developing in the more competitive Scottish Second Division had been rebuffed by the SFA, he was at least able to challenge them by regularly staging Lisbon Lions versus Quality Street Gang practice matches at training. Instead of being over-awed by the legendary first-team figures, these cocksure kids fancied their chances and occasionally won the largely-attended bounce games.

So why has the wider football community not heard of the Quality Street Gang? Unlike Sir Alex Ferguson’s extensively lionized class of ’92, many of these underlings to the nonpareil Lisbon Lions capitulated in dramatic fashion and the gang broke up before realizing their incredible collective potential.

Some of the fabled Quality Street Kids went on to become revered throughout the football world with players such as Kenny Dalglish, Danny McGrain, Lou Macari and Davie Hay achieving incredible success for club and country in the seventies and into the nineteen eighties but while the fortuitous few attained incredible glories, there were other phenomenal talents who fell by the wayside in spectacular style.

Scotland’s 1973 Player of the Year, George Connelly, from a small mining village in Fife, walked away from the game at just 26. He had been compared to Franz Beckenbauer and was the natural successor to the seemingly indestructible Billy McNeill but mental illness, alcoholism and a disdain for the limelight drove him out of the game at a lamentably young age.

Tony McBride was a “pocket edition of Jimmy Johnstone” according to Jock Stein but he failed to make a single first team appearance on account of his frequent brushes with the law, much to the annoyance of the taskmaster Stein.

Brian McLaughlin was good enough to break into the first team at just 16. Yet his unfortunate and tragic downfall was prompted by a brutal career-threatening onfield assault in 1973 at the hands of a journeyman Aidrieonian thug, who is remembered for nothing else in the game. McLaughlin had it in him to be the Lubomír Moravcík of his generation but his sparkling career was molested and his grotesque injury literally brought a tear to Jock Stein’s eye.

The enigmatic Pat McMahon became Celtic’s first post-Lisbon signing and burst onto the scene in the 67-68 season with his Beatlesesque flowing locks and fresh-faced good looks. McMahon was an intellectual, who had trained in the Priesthood as a youngster before moving down to London. Much to his chagrin, he returned to reserve team football after 5 goals in 6 first-team matches and his Celtic career hit the skids. Oddly, he made no further first team appearance and was released after just two seasons.

And there were more. Paul Wilson could be considered something of an unsung hero of the wider Gang as his Celtic career was both lengthy and successful with his place in the club’s history being assured by virtue of his Scottish Cup-winning performance of 1975. Vic Davidson was undoubtedly a player who progressed on a level footing with Dalglish and Macari but only up to a certain point before his career tailed off and his potential was to be eternally considered as unfulfilled. Influential and popular members of the gang, Davie Cattanach and Jimmy Quinn were slightly older and their successes were enjoyed mainly at reserve level. And then there was John Gorman, a player who proved beyond doubt that Jock Stein was wrong to let him go. Not to mention the huge amount of talented young players who didn’t make it for any number of reasons, many of whom may consider themselves as unlucky as they may have succeeded at any other time in the history of Celtic Football Club.

The Quality Street Gang is as much a story about the transformation in attitude from those loyal Brylcreemed round-collared 1960s servants, who encapsulated Jimmy McGrory’s 1950s pipe-smoking discipline, to their floppy-fringed, sideburned superstar counterparts of the 1970s.

By the time of their European Cup semi-final first leg against Atlético Madrid in 1974, Celtic had reached two finals, four semi-finals and two quarter-finals in European competition in just eleven seasons.

However, the Quality Street Gang were already fragmenting and Lou Macari had joined Manchester United for more pay in 1973. Davie Hay would follow him across the English border for Chelsea 1974 after going on strike with George Connelly over pay conditions and it wouldn’t be long before Kenny Dalglish left to become the King of the Kop. Celtic fans were left wondering just what might have been had the Quality Street Kids all reached their peak in the green and white hoops of Celtic.

Over forty years on, it is easy to get trapped in time when looking back through the scrap book of a football career which promised so much. The teenage Celtic babes of 1968, who seemingly had the world at their feet when they posed for the baying Scottish press in their green Celtic blazers at Glasgow airport prior to their Italian international youth tournament, may all have had the same destination stamped on their airline ticket on that Summer’s day in May but they would all ultimately travel on vastly different journeys over the next four decades. Some would enjoy the emphatic highs of the game at the very top level whilst others would suffer a far more grim fate in living with the melancholia that hangs heavily over the harsh reality of what-might-have-been.

The Quality Street Gang were brought up by the greatest football team Scotland has ever produced and the result was a group of young prospects who even threatened for a spell to emulate their predecessors. The kids were cultivated on the Barrowfield training ground and the Lisbon Lions passed on the torch so that their successors could continue their incredible forays into the latter stages of European football’s most prestigious tournament. Celtic won nine successive league titles but never reclaimed the honour of winning the European Cup for a second time. If only the Quality Street Kids had all hit their peak together there is no doubt that the Parkhead side would have lifted that glorious prize more than once.

With such a blend of monumental successes, likeable rogues and enigmatic underachievers it is perhaps no surprise that the 2013 Quality Street Gang book is now being adapted for a major documentary film by director, Luke Massey. Celtic and Liverpool fan Massey, on the back of his success with war horror film Armistice, opted for this intriguing group of young footballers as his next project after reading the book over Christmas.

The bittersweet tale of unfulfilled potential has struck a chord with football fans for generations. Many of us can relate to the peculiar, all-too-human idiosyncrasies, which often contribute to the downfall of some of our greatest cult heroes. Icons who threw it all away at the mercy of alcohol, slow horses, loose woman or all of the above, and worse. We seem drawn to these slightly broken characters and their urchinular charms and, once we have become intoxicated by their incredible talents, we always have it in us to forgive their irresponsible ways; we always have another last chance to hand out to them because we know they will always let us down. That’s why magnificent players like Robin Friday, Andy Ritchie and George Best became and remain cult icons of the British game. Perhaps we see a human side and fragility to them that we can identify and sympathize with.

Despite the magnificent successes of Dalglish, Hay, McGrain and Macari, as the end credits roll on The Quality Street Gang, Celtic fans will be left wondering, “what if?”

By Paul John Dykes

Tony McBride