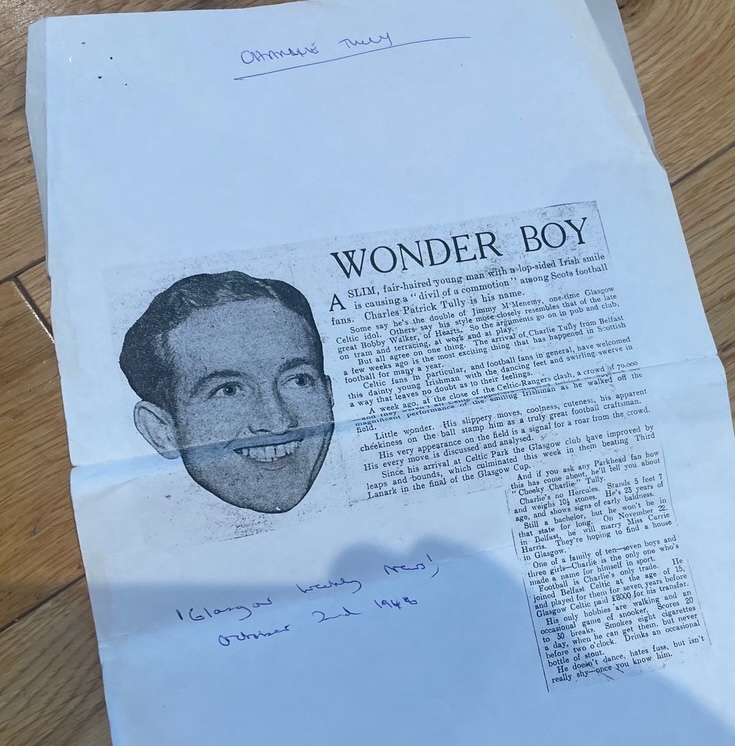

Charlie Tully

By Tommy Mac (Thomas Mc Sorley)

Footballer Charlie Tully was my greatest hero, in more ways than one.

In 1948 I was in the Army when Celtic signed Charlie Tully from Belfast Celtic for the enormous signing on fee at the time of £8,500. Of course we were hearing about him by way of the Forces Radio, but he was to play a part in my life I couldn’t even dream about at the time. He was so popular in Glasgow that the joke doing the rounds were like: The Pope was visiting Glasgow and Charlie Tully was showing him around. The people in the crowd turned to each other and said, “Who is that with Charlie Tully?” His prowesss on the football pitch was becoming legendary.

The letters I received from my father were full of wonder at this player and he sent me all sorts of cuttings from newspapers telling of his exploits. One I can remember seeing for myself when I got home was the match against Falkirk at Brockville. Tully took a corner kick and scored direct, but the referee ruled the goal out because the ball was outside the corner arc. So Tully grabbed the referee and took him accross to the corner where the kick was to be re-taken. What did Tully do? He promptly took the kick again AND AGAIN SCORED DIRECTLY!!

But I am getting ahead of myself as this was in the future. So to go back to 1948… In October of that year I had my accident and was in a very bad way indeed. In so much of a bad way that the Army decided to bring my father over to Italy to see me, telling him on the way over that he was probably coming over to bury me. When my father arrived I was still drifting in and out of consciousness, which lasted for five days and nights. Sometimes when I awoke I could see my father with the tears running down his face.

Still when I had stabilised, he took a life-sized poster of Charlie Tully and pinned it above my bed. He said to me, “Come on son, you will have to get better so you can come home to see this wonderful player. He is even better than Patsy Gallagher.” Now! For my father to admit to something like that meant that Charlie Tully must be very special indeed. From then on I gradually improved and the doctors all agreed that the poster of Charlie Tully might have been the vital spark I needed to make me want to live. My chances before this looked very shaky.

My Dad stayed with me for nineteen days. He was made a Sergeant in the Yorkshire Light Infantry so that he had a place to stay and my mother would get an allowance all the time he was with me. He only left me after my leg was amputated and my condition had been reduced from Critically Ill to Seriously Ill – this was just Army jargon, but it meant I was going to live after all and so my Dad could go home. It took a whole year to get home, plaster of paris gradually being removed from my arms, my head, my pelvis and eventually my leg (when the stitches were removed) showing signs of healing, enough for me to get about on crutches.

Can you wonder, then, that my hero is Charlie Tully? He saved my life. I am convinced of this, and I am happy to say I went on to watch him play some wonderful stuff on the football pitch. His fondness for the bottle only made him all the more endearing and made him out to be just like “one of us.”

Next to Pele, he was the finest player I ever saw.

The Scotsman: A loyal servant

April 19, 2003

Author: JOE McAVOY

Tully’s reputation was cemented, as is often the case with Celtic’s greatest players, with an outstanding performance against Rangers weeks after his arrival. This catapulted him to the status of cult hero – “Tully Mania” gripped the East End. Unlike today’s iconic players, who crave lucrative contracts and fan adulation in equal measure, Tully was a great servant of the club, notching up 319 appearances and scoring 47 goals throughout an illustrious 11-year career. Most fans reckon he is the best inside-left ever to have played for the club.

“Do you enjoy playing for your country, Mr Ramsey?” asked Charlie. “I do, Mr Tully,” replied the ever-polite future knight. “Make the most of it today, then,” came back the irrepressible Irishman, “it might be the last chance you get.”

During the St Mungo Cup Final on August 1, 1951, Celtic were 2-0 down when Tully took a throw-in. He deliberately directed the ball off Dons’ Davie Shaw’s back to win a flag kick. Tully flighted over the corner, Sean Fallon scored and this started a comeback that saw Celtic run out 3-2 winners.

In the twilight of his career, Tully spent brief periods on loan to Stirling Albion and Rangers before leaving Scotland in 1959. He eventually went into club management in Ireland.

Charlie Tully was given a free transfer on Wednesday, September 2, 1959.

Tully made 319 appearances for The Bhoys during his 11 seasons at Celtic Park.

Charlie Tully died peacefully in his sleep on 27th July 1971 aged 47 at his home in Belfast, a few months after playing in a charity match at Meadowbank. During the funeral procession, the Falls Road was packed with mourners from both sides of the sectarian and footballing divide.

The hero who came to tea

Published Date: 19 April 2003(The Scotsman (link))

At the moment he was illustrating a Bible for schools. He’d shown me a drawing for the Cure at Capharnaum and, as an exercise, made me read aloud the caption: “They could not get in because the house was crowded out, even to the door. So they took the stretcher onto the roof, opened the tiles and let the sick man down .”

I was about eight or nine at the time. It was dead easy.

It was a Sunday and felt like a Sunday. Family Favourites was on the wireless. My father sat beneath the window for the best light.

“What you doing ?”

He held up the drawing.

“Abraham and his son, Isaac,” he said. A man with a white beard beside a boy carrying a tied-up bundle of sticks.

“Where is the victim for the sacrifice? That’s what the boy is saying.” My father put on a scary, deep voice and said,

“Little does he know …” He drew quietly for a while. The pen scratched against the paper and chinked in the ink bottle. He had a pad on the table and sometimes he made scratches on it. “Just to get the nib going.” Sometimes the pen took up too much ink and he shook it a little. “You’re no good if you can’t make something out of a blot.”

The hall door opened and footsteps came in off the street. My father stopped and looked up. It was my cousin, Brendan, who was a year and two months older than me. He was a good footballer.

“It’s yourself, Brendy.”

Brendan stopped in the middle of the floor and said, “Charlie Tully’s in our house having a cup of tea.”

“Go on. Are you kidding ?”

“No.”

My father gave a low whistle.

“This we will have to see.” He wiped his pen on a rag, then rinsed it in a jam jar of water. He blew on his drawing then folded the protective tissue over it.

“Come on.” All three of us went across the road. The only car parked on the street belonged to Fr Barney.

“Did Barney bring him?” Brendan nodded.

“And Terry Lennon.”

Terry Lennon was a blind church organist. He had a great Lambeg drum of a belly with a waistcoat stretched tight over it. He would sit in the armchair by the fire smoking constantly, never taking the cigarette from between his lips. A lot of the time he stared up at the ceiling – his eyelids didn’t quite shut and some of the white of his eye showed. Now and again he would run his fingers down the cigarette to dislodge the ash on to his waistcoat. Aunt Cissy called him Terry Lennon, the human ash-tray.

When we went in Terry Lennon was in his usual chair. Fr Barney stood in front of the fire with his hands behind him. On the sofa was a man, still wearing his raincoat, drinking tea. His hair was parted in the middle. He was introduced to my father as Charlie Tully.

“You’re welcome,” said my father. “Is that sister of mine looking after you?”

Charlie Tully nodded.

“The best gingerbread in the northern hemisphere,” said Fr Barney. “That’s what lured him here.”

“Where’s the old man?” said my father.

“The last I saw of him was heading up to the lavatory with the Independent.”

“He’ll be there for a week.” My father turned to the man in the pale raincoat.

“I bet he was delighted to see you, Mr Tully – he’s a bit of a fan.”

“Oh he was – he was.”

“So – how do you like Scotland?”

“It’s a grand place.”

“Will Mr Tully have a cigarette?” Terry Lennon reached out in the general direction of the voice with his packet of Gallagher’s Greens.

“Naw, he only smokes Gallagher’s Blues,” said Aunt Cissy and everybody laughed.

“If you’ll forgive me saying so Mr Tully,” said Terry Lennon, “the football is not an interest of mine. You understand?”

“I do. You were making some sound with that organ this morning.”

“Loud ones are great.” Terry Lennon laughed. “Or Bach. Bach is great for emptying the place for the next mass. The philistines flee.”

There was a ring at the door and Brendan went to answer it. When he came back he said it was Hugo looking for a drink of water.

“And run the tap for a while,” said Aunt Cissy laughing. “Bring him in.”

“The more the merrier,” said my father.

“Wait till you hear this, Mister Tully. Our Hugo.” Brendan went into the kitchen and ran the tap very fast into the sink. He carried a full cup into the room and called Hugo from the door. Hugo edged into the room and accepted the cup. There was silence and everybody watched him drink. Hugo was a serious young man who was trying to grow a beard.

Fr Barney joined his hands behind his back and rose on his toes. He said, “So you like to run the tap for a while ?”

“Yes, Father.”

“And why’s that?”

“The pipes here are lead. And lead is poison. Not good for the brain.”

“The Romans used a lot of lead piping,” said Fr Barney, winking at Charlie. “Smart boys, the Romans. They didn’t do too badly.”

“No – you’re right, Father. But maybe it’s what destroyed their Empire,” said Hugo. “Being reared to drink poison helps no-one.”

Fr Barney sucked in his cheeks and rolled his eyes.

“I need a whiskey after that slap down.” Aunt Cissy moved to the sideboard where the bottle was kept . “Cissy, fill her up with water, lead or no lead. Will anybody join me? What – no takers, at all?”

He held up his glass. “To Mister Tully here. God guide your golden boots.”

Granda came downstairs and had to push the door open against the people inside.

“What am I missing?” he said.

“A drink,” said Fr Barney. Granda looked around in mock amazement.

“He’s getting no drink at this time of the day,” said Aunt Cissy. Granda was still wearing his dark Sunday suit and the waistcoat with his watch-chain looped across it. On his way to mass he wore a black bowler hat.

“It’s getting a bit crowded in here,” Granda said, looking around the room. “Reminds me of the day McCormack sang in our house in Antrim. There was that many in the room we had to open the windows so’s the neighbours outside could hear him.”

“Count John McCormack?” said Charlie Tully.

“The very one.”

“How did the maestro end up in your house?”

“Oh, he was with Terry there, some organ recital.”

“And what did he sing? ”

“Everything. Everything but the kitchen sink. Down by the Sally Gardens, I hear you calling me.”

“It was some show,” said Terry Lennon, putting his head back as if listening to it again.

“Would you credit that?” said Charlie. “I met a man who knows Count John McCormack.”

There was a strange two note cry from the hallway, “Yoo- hoo.”

“Corinna,” said Cissy and pulled a face. The door was pushed open and Corinna and her sister, Dinky, stood there.

“Full house the day,” said Corinna. She eased herself into the room. Dinky remained just outside.

“The house is crowded out, even to the door,” said my father.

“Is there any chance of borrowing an egg, Cissy. I’d started the baking before I checked.” Cissy went into the kitchen and came back with an egg which she handed to Corinna.

“Thanks a million. You’re too good.” Corinna stood with the egg between her finger and thumb. “What’s the occasion?” She vaguely indicated the full room.

“Charlie Tully,” said Cissy. “This is Corinna Coyle. And her sister Dinky.” Cissy pointed over heads in the direction of the front hall. Dinky went up on her toes and smiled.

“A good looking man,” said Corinna.

“Worth £8,000 in transfer fees,” said Fr Barney.

“He’s above rubies, Cissy. Above rubies.” And away she went with her egg and her sister.

“So,” said Granda, “will we ever see Charlie Tully playing again on this side of the water?”

“Maybe.”

“Internationals,” said Hugo.

“But it’s not the same thing,” said Granda, “as watching a man playing week in, week out. That’s the way you get the whole story.”

“There’s talk of a charity game with the Belfast boys later in the year,” said Charlie.

“Belfast Celtic and Glasgow Celtic?” Granda was now leaning forward with his elbows on the table. “There wouldn’t be a foul from start to finish.”

“Where’d be the fun in that?” said Fr Barney. “Cissy, I’ll have another one of those.” Cissy went to the sideboard and refilled the glass.

“Remember you’ve a car to drive.” Barney ignored her and pointed at my father, “Johnny there would design you a programme for that game. For nothing. He’s a good artist.”

“Like yourself Charlie,” said Granda.

“Is that the kinda thing you do?” Charlie said.

“Yeah sure,” said my father. Barney started mock shouting as if he was selling programmes outside the ground. Some of his whisky slopped over the rim of the glass as he waved his arms. My father smiled.

“Have you been somewhere – before here?”

“On a Sunday morning?”

Barney looked over to Charlie Tully. “Johnny does work for every charity in the town. The YP Pools, the St Vincent de Paul, the parish, even the bloody bishop – no friend of mine – as you well know – his bloody nibs. Your Grace.” He gave a little mock inclination of the head. Cissy ordered Brendan out of his chair and told Barney to sit and not be letting the side down.

“So Charlie,” said Granda, “the truth from the insider – is there no chance of Belfast Celtic starting up again?”

“Not that I know of.”

“We gave in far too easily. In my day when somebody gave you a hiding, you fought back.”

“Aye, it’s all up when your own side makes you the scapegoat,” said Aunty Cissy.

“I mean to say,” Granda’s voice went up in pitch. “What were they thinking of ?”

“The game of shame.”

“A crowd of bigots.”

“They came streaming on to that pitch like .. like .. bloody Indians.”

“Indians are good people,” said Hugo.

“…and they kicked poor Jimmy Jones half to death. Fractured his leg in five places. And him one of their own. It ended his career.”

“Take it easy, Da,” said Fr Barney and slapped the arm of his chair.

“You were at the game?” said Charlie Tully.

“Aye and every other one they’ve ever played,” said Granda. “I don’t know what to do with myself on a Saturday afternoon now. I sometimes slip up to Cliftonville’s ground but it’s not the same thing.

Solitude. It’s well named.” Granda was shaking his head from side to side. “I just do not understand it. What other bunch of people would do it? The board of directors,” he spat the words out.

“The team gets chased off the pitch, its players get kicked half to death and what do they do? OK, we’re going to close down the club. That’ll teach you. In the name of Jesus…” Granda stopped talking because he was going to cry. He looked hard at the top of the window and he kept swallowing. Again and again. Nobody else said anything. “Why should we be the ones sacrificed? Is there no-one on our side who has any guts at all?”

“Take it easy,” said my father. “They have the sectarian poison in them.” He reached out and put his hand on Granda’s shoulder. Shook him a little. Granda recovered himself a bit and said, “It would put you in mind of the man who got a return ticket for the bus – then he had a row with the conductor – so, to get his own back, he walked home. That’ll teach them.”

There were smiles at that. The room became silent.

“It was a great side,” said Charlie Tully at last. “Kevin McAlinden, Johnny Campbell, Paddy Bonnar …”

“Aye.”

“And what a keeper Hugh Kelly was.”

“Aye and Bud Ahern…”

“Billy McMillan and Robin Lawlor.”

“Of course.”

“Jimmy Jones and Eddie McMorran and who else?”

“You’ve left out John Denver.”

“And the captain, Jackie Vernon.”

“And yourself, Charlie,” said Granda. “Let’s not forget yourself, maestro.”

Sometime later that year – which became known to Granda as “the year Charlie Tully called” as opposed to “the year McCormack sang in the house in Antrim” – I noticed drawings and sketches of my father’s lying about the house. They were of players in Celtic hoops in the act of kicking or heading a ball. Their bodies were tiny but their heads were made from oval photos of the real players.

It was many years later – half a century, in fact – before I would remember these drawings again. My father died when I was 12 and my mother was so distraught that she threw out all his things.

If she was reminded of him she would break down and weep, so every scrap of paper relating to him had to be sacrificed.

Recently, I was in Belfast and I wondered if there might be a copy of the programme lying around Smithfield market. I found a small shop entirely devoted to football programmes, so I went in and told them what I was looking for – a Belfast Celtic v Glasgow Celtic match programme from the early 1950s.

The man looked at me and said: “Put it this way. I’m a collector and I’ve never seen one.”

I was disappointed. Then he said, “If you do catch up with it, you’ll pay for it.”

“How much?” I was thinking in terms of 20 or 30 quid.

“A thousand pounds. Minimum.”

I’m not really impressed by that kind of rarity value – but in this case I thought, “Good on you, Johnny. After all the work for charity.” If that price is accurate I don’t want to own the real thing – but I wouldn’t mind seeing a photocopy. A photocopy would be good. Above rubies, in fact.

Tully after Celtic

The career of Cheeky Charlie Tully was one spent in the brightest of lime lights and when he made his final tearful, bow at the Celtic Supporters Rally at St Andrew’s Hall in November 1959, the 3,000 Celtic fans cheering him to the rafters, as he prepared to leave the Hoops, were under no illusions – they knew Charlie would stay close to the headlines, no matter where he went.

Cork in Ireland would be the first destination and as Charlie prepared to line out at Hibernians as player/manager. Cork’s Chairman, John Crowley, was hoping his new player/manager’s boots would still have a sprinkling of Tully magic to help his team make an imprint on the Irish football scene.

And he didn’t have to wait long for the magic to arrive, as Hibs hurtled towards the FAI cup final in 1960, only for a fall at the final hurdle against Dublin’s Shelbourne.

In March of that year, the Mardyke club also recorded their biggest ever win, firing 10 goals past a helpless Transport club, as spectators and reporters and news men swelled the gates.

Three future Lisbon Lions would feature in Cork in May 1960, as a youthful Celtic side played an exhibition match against Charlie’s new club. Celtic Chairman Robert Kelly’s fondness for Tully hadn’t waned and, even after a strained finale to his career in Glasgow, he was happy to be in Charlie’s company once again.

A wonderful black and white image of the day captures the two sides and the magic of the time.

As Bertie Auld, John Clark and Neilly Mochan crouch in the front row of the lineup, standing at the back is a 20 year old Billy McNeil, with his arm draped lovingly around his hero, the ageing Charles Patrick Tully.

Despite his advancing years, Charlie played on, until, on January 8, 1964, he accepted a managerial post closer to home, with Irish football minnows Bangor FC, based in the seaside town on the north coast of County Down.

Before Charlie arrived for his first of two spells at Clandeboye Park, Bangor had finished joint bottom of the league with Cliftonville. They were also without a home win all season – their record reading two draws and six defeats as Tully rolled into town.

Things were so bad Charlie quipped; “Even the seagulls have deserted Clandeboye!”, but on a shoestring budget, and with his famous Irish blarney, Charlie began to set the league alight.

He used his personal magnetism to lure very useful players, including a famous ex-Celt in Willie Fernie, along with Italian-born winger Stevie Ginalti, also from Glasgow.

Both were drawn to an unremarkable club to play for a remarkable man and Tully also drew handy Dubliners Sonny Rice and Eamonn Farrell.

Life was tough in the trenches and the ever-enthusiastic and sometimes volatile Tully could reach a volcanic boiling point in the dugout. He wore his heart on his sleeve, abhorred anything less than a professional approach to football and was in constant ‘hot water’ with the powerful figures who ran the Irish Football Association and the Irish Football League.

On one occasion, Charlie burst onto the field of play to remonstrate with a referee, earning him a red card and a heavy league fine.

His player and assistant manager Jim Emery once remarked ‘In modern day football, Charlie would be banned every other week because he always called a spade a spade!”

On another occasion, he fired a broadside at the make-up of the Northern Ireland international squad, made flippant pokes at both soccer commentator Ronald Rosser and IFA President Harry Cavan, leading him again to be hauled over the coals by the IFA.

He was a reporter’s dream and a snappers delight, perching his trademark Trilby hat at a jaunty angle to match his carefully created ‘Cheeky’ persona for the photographers to aim their lenses at and his Bangor team, affectionately dubbed the ‘Seagulls’ regularly made the headlines.

Irish news reporter Denis O’Hara, who would later be Charlie’s Ghost Writer at the morning daily, would make occasional trips from Belfast to Bangor, reporting on how Tully and the minnows were progressing.

He recalls how he once saw Charlie barracking a player for hitting a corner kick wide – a cardinal crime in Charlie’s eyes.

After two years, he moved inland to manage Portadown FC before returning to Bangor in January 1968 for an historic managerial spell.

On May 22, 1970, the madcap Messiah led Bangor to the Promised Land by winning their first senior trophy.

It took four collisions with north Down neighbours Ards at Solitude (three 1-1 draws, then a 3-2 win) to clinch the County Antrim Shield.

One euphoric Bangor youth, clamouring for Charlie’s autograph afterwards, cried out to Charlie: “Mr Tully, does this win get us into Europe?”

The reply was typically Charlie Tully, as he chuckled: “No son, it doesn’t even get us into County Antrim!”

Seven months later, Bangor also bagged the old City Cup, proving Tully’s magic hadn’t deserted him.

Despite his successes at Bangor and Cork Hibs, Belfast Celtic were Charlie’s real passion and he always felt these roles were simply rehearsals for the day the Grand Old Club would return to dominate Irish football with him at the helm.

In an interview shortly before his death, in an article in which he is pictured clasping the European Cup, he laid out his plans for working with surviving board members to resurrect the Belfast Stripes.

With typical Tully bluster, he declared that within two years he would have Belfast Celtic in Europe, using a mix of promising youngsters and veteran Glasgow Celts Bertie Auld, Stevie Chalmers and Charlie Gallacher, whom he planned to recruit.

Charlie regularly crossed the Irish sea to visit the team and the city who had adopted him as a favourite son.

A major Scottish travel company had secured Charlie’s services for the trip to Portugal in 1967 and as 30 plane loads of Scottish Celts disembarked in Lisbon, there to greet them was their hero.

Denis O’Hara remembers him being mobbed by adoring fans and the adulation extended to the official Celtic travelling party who immediately invited Charlie to attend the pre-game meal in Estoril with the players and their families, with a starry eyed Irish News journalist in tow.

After the victory, Charlie was asked for his thoughts on the game and one journalist brazenly asked Tully whether he would have made the team on that hot night in Lisbon.

With typical Irish charm and a fair degree of modesty, Charlie responded, ‘Ah now, sure maybe I could have taken the corners’, with the memories of Charlie scoring directly from the set-pieces flooding back to the hacks.

He continued to follow Celtic and in 1970, it seemed certain that the European Cup would once again land on Scottish shores and following the 1967 European Cup milestone, there was high hopes of a second success.

On March 4, 1970, Celtic secured a quarter final tie against top Italian side Fiorentina in what promised to be another nail-biting saga after a coin-toss win over Benfica.

Charlie always had free access to Celtic Park, thanks to his old colleague Sean Fallon of Sligo – Jock Stein’s shadow at Celtic – but on this night he stuck with O’Hara, standing at the back of the old claustrophobic and creaking Press area, by pretending to be a Media Messenger.

During the action, Tully’s trademark Trilby took to the air, Frisbee-like, in a show of instinctive emotion, landing on top of a crusty Italian soccer writer.

On learning the culprit was none other than Charles Patrick, the same journalist rose from behind his typewriter and asked for Tully’s autograph!

Beating the Italian giants propelled Celtic into a mouth-watering war with Don Revie’s white-shirted Leeds United, widely regarded as one of the best teams in Europe.

Jock Stein’s side upset the script with an April semi-final, first leg, 1-0 win at Elland Road and a ticket for Tully to gain entry to the Press Area of Hampden Park was duly obtained.

The gripping second-leg showdown was a sensation!

Leeds leveled through Billy Bremner and when John ‘Yogi’ Hughes regained the initiative for the Hoops, Charlie’s trademark Trilby was once again flung down the row of press seats, landing on the typewriter of the late Hugh ‘Sniffer’ Taylor of the Daily Record.

An agitated pressman roared: “Who did that?”, but when Taylor looked round and saw Charlie standing up and cheering the Hughes’ goal, he simply waved, and shouted; ‘Congratulations Charlie!”

No doubt, the press men remembered fondly how Charlie once kept them stocked with incredible stories and they were willing to forgive him his boisterous love for the club he adored.

Sadly, destiny would visit the Netherlands in the final, as an up and coming Feyenoord side shocked a complacent Celtic by taking the European Cup and breaking the hearts of Stein’s Glasgow Hoops.

In November 1970, when Celtic came to Dublin to play Waterford United at Lansdowne Road in a European Cup tie, Charlie was given a standing ovation during half-time, as Celtic fans spilled onto the pitch to cheer their hero.

Charlie’s aide-de-camp, Jim Emery, remembers the eventful trip, and the supporters chanting Charlie’s name as he waved at them from the stand.

On the trip home, they stopped at Drogheda in County Loth to visit a bar belonging to the Irish Tenor Patrick O’Hagan, who once filled the halls of the Empire theatre in Glasgow.

Celtic fans returning from Lansdowne Road soon found out that Charlie had decamped and the bar was reduced to standing space.

At one point, Charlie was pulled from the pub on the shoulders of the throng to be carried along the street shoulder high.

At closing time, O’Hagan slipped Charlie back to his family home, where, over nips of poitín, the Tenor treated the gathering to songs from his son Johnnie – who would later spellbind the entire continent of Europe, as Johnnie Logan, with his hit single ‘What’s another year?’

Unfortunately Charlie wouldn’t see another year.

On a Monday night deep in mid-summer 1971, as war raged all around the Falls Road, Charlie took his usual place at the end of the counter at Beacon’s Bar, his closest friend and former Belfast Celtic team mate Jackie Vernon at his side.

Glasgow Celtic had tried to buy Jackie, back in the 40’s, but refused to meet the asking fee, believing £10,000 was far too much to pay for a defender.

Instead, Robert Kelly parted with £8,000 for a skinny wing wizard called Charles Patrick Tully and the rest is history.

As the two men digested the weekend’s football results and planned their days ahead, neither realized they would never see each other again.

In the early hours of Tuesday, July 27, Cheeky Charlie Tully, aged 47 years old, slipped quietly out of the world in his St James’s Road home with his sweetheart Carrie Harris by his side.

Telegrams flooded in from around the world for the man who had died too soon and the front pages of Ireland’s tabloids replaced stories of bombs and bullets with the sad tale of the loss of the Clown Prince of Football.

One reporter, The Observer’s John Rafferty, remarked sadly that; “It was strange (that Charlie) should have gone so peacefully. It was not his way in life!”

In Glasgow, Celtic were preparing their own tributes and Jock Stein immediately informed the entire Celtic team that each would be required immediately to travel to Belfast as an official party to pay their respects to the man who saved Celtic when he dragged them almost single handedly from the doldrums of the 1940’s.

However, in a town preparing to be convulsed by the ravages of internment without trial, the Royal Ulster Constabulary had other ideas, informing the Glasgow club that they would not be responsible for their safety while entering through the Ports.

Stein did arrive in Belfast, undeterred, with club Captain Billy McNeill and the two men shouldered Charlie’s remains with another Celtic legend, Bertie Peacock as it left the church of Saint John the Evangelist, close to Charlie’s home.

On his final journey to Milltown Cemetery, where Celtic fans will gather on the 40th anniversary of Charlie’s death this year, Tully would have no doubt revelled in the fact that he could still pull the biggest crowd in town, even if he would have to accept that, in death, this was one game he could never win..…..

Obituary from The (London) Times, 29th July 1971

A loyal servant

BORN in Belfast, 1924, Charles Patrick Tully signed from Belfast Celtic in June 1948. The names were the same, the strips were the same, even the clubs’ aims were the same – to alleviate the plight of beleaguered working-class Catholics.

Tully’s reputation was cemented, as is often the case with Celtic’s greatest players, with an outstanding performance against Rangers weeks after his arrival. This catapulted him to the status of cult hero – “Tully Mania” gripped the East End. Unlike today’s iconic players, who crave lucrative contracts and fan adulation in equal measure, Tully was a great servant of the club, notching up 319 appearances and scoring 47 goals throughout an illustrious 11-year career. Most fans reckon he is the best inside-left ever to have played for the club.

His most notable game was in a 1953 cup tie against Falkirk at Brockville, when Tully scored not one but two sensational goals – direct from the corner kick. (Not even Beckham could bend it like that, twice.) Celtic were 3-2 winners. Tully had already scored a goal from the corner flag in 1952, when, earning one of his ten international caps for Northern Ireland against England, he scored another brace to level the match. It became something of a habit.

In the twilight of his career, Tully spent brief periods on loan to Stirling Albion before leaving Scotland in 1959. He eventually went into club management in Ireland.

Tully died in 1971 aged 47 at his home in Belfast, a few months after playing in a charity match at Meadowbank. During the funeral procession, the Falls Road was packed with mourners from both sides of the sectarian and footballing divide.

The Pat Woods Files – Charles Patrick Tully

By Matt Corr 12 July, 2024 No Comments

[The Pat Woods Files – Charles Patrick Tully]

The Pat Woods Files – Charles Patrick Tully

Charlie Tully

Part 1: Wonder Boy

A few months back, legendary Celtic author and historian Pat Woods shared some old newspaper articles with me, all relating to the life and career of Charlie Tully, a wonderful Celt whom Pat had the privilege to see play in those hoops. Charlie was the source of so many hilarious stories over the years, many of which Pat shares with relish. We agreed at that point that with Charlie’s centenary on the horizon, we would hold off until then to publish.

The great man would have celebrated his 100th birthday yesterday, and often joked that he wished he had been born a day later, ‘just for the craic!’

The first article we want to share is from the Glasgow Weekly News of 2 October 1948, seven days after Charlie had teased and taunted the Rangers defence as Celts won a League Cup sectional clash 3-1 at Celtic Park. That was a third straight win in the competition for the Hoops, having earlier beaten Scottish champions Hibernian 1-0 at Celtic Park and Clyde 2-0 at Shawfield, and 48 hours later Jimmy McGrory’s men lifted a first trophy since the war, beating Third Lanark 3-1 in the Glasgow Cup final in front of 87,000 spectators at Hampden.

Of course, Celtic of that era being Celtic, they then proceeded to lose the next three League Cup games to exit the competition, including a 6-3 home defeat by Clyde!

The war years had been frustrating and cruel to Celtic supporters, but two beacons of hope had arrived in recent times, a wing-half called Bobby Evans and now this genial inside-forward from Belfast, Charlie Tully. Here is how the Glasgow Weekly News reported on his impact back in October 1948.

Charlie Tully on the ball

The article is headed Wonder Boy…

“A slim, fair-haired young man with a lop-sided Irish smile is causing a ‘divil of a commotion’ among Scots football fans. Charles Patrick Tully is his name.

Some say he’s the double of Jimmy McMenemy, one-time Glasgow Celtic idol. Others say his style more closely resembles that of the late great Bobby Walker, of Hearts. So the arguments go on in pub and club, on tram and terracing. At work and at play.

But all agree on one thing. The arrival of Charlie Tully from Belfast a few weeks ago is the most exciting thing that has happened in Scottish football for many a year.

Celtic fans in particular, and football fans in general, have welcomed this dainty young Irishman with the dancing feet and swirling swerve in a way that leaves no doubt as to their feelings.

A week ago, at the close of the Celtic-Rangers clash, a crowd of 70,000 – and they weren’t all Celtic supporters – lingered behind to applaud the magnificent performance of the smiling Irishman as he walked off the field.

Little wonder. His slippery moves, coolness, cuteness, his apparent cheekiness on the ball stamp him as a truly great football craftsman.

His very appearance on the field is a signal for a roar from the crowd. His every move is discussed and analysed.

Since his arrival at Celtic Park the Glasgow club have improved by leaps and bounds, which culminated this week in them beating Third Lanark in the final of the Glasgow Cup.

And if you ask any Parkhead fan how this has come about, he’ll tell you about “Cheeky Charlie” Tully.

Charlie’s no Hercules. Stands 5 feet 7 and weighs 10½ stones. He’s 23 years of age [he was 24 at that time] and shows signs of early baldness.

Still a bachelor, but he won’t be in that state for long. On November 22, in Belfast, he will marry Miss Carrie Harris. They’re hoping to find a house in Glasgow.

One of a family of ten – seven boys and three girls – Charlie is the only one who’s made a name for himself in sport.

Football is Charlie’s only trade. He joined Belfast Celtic at the age of 15 and played for them for seven years before Glasgow Celtic paid £8,000 for his transfer.

His only hobbies are walking and an occasional game of snooker. Scores 20 to 30 breaks. Smokes eight cigarettes a day, when he can get them, but never before two o’clock. Drinks an occasional bottle of stout.

He doesn’t dance, hates fuss, but isn’t really shy – once you know him.”

Hail, Hail,

Matt Corr, with grateful thanks to Pat Woods for provision of this article.