| World War One | The War Years | Celtic Games | Tournaments |

A minute’s silence at Celtic Park

By: Newsroom Staff on 09 Nov, 2012 17:01 THIS Sunday, November 11, marks the 94th anniversary of the ending of the First World War. And there will be a minute´s silence in memory of all those who died in that war and in all other conflicts.

In 1918, at 11 minutes past 11 on the 11th day of the 11th month, the guns finally fell silent after four years of bloody fighting which claimed the lives of over 16million people

It was a conflict which affected individuals, families, communities and organisations in every country caught up in the war, and Celtic Football Club was no different.

As the world was plunged into war in 1914, all aspects of life changed and as millions headed off to the Front, the Great War was to have its affect on Celtic and a number of its players.

As the war progressed the implications for the game were significant. Player salaries were reduced, employment in munitions factories on Saturdays resulted in a sharp fall in attendance, both by spectators and players and the pressure to complete the fixture card was significant.

Indeed, Celtic was forced to play two matches, against Raith Rovers and Motherwell, on the same day in 1916 in order to comply.

Football grounds were viewed as an ideal venue for recruitment drives and during one such event Celtic manager Willie Maley endorsed a mock trench warfare at Celtic Park designed to lure players and spectators alike to the Front.

Such drives had their successes and the supporters and officials of Hearts and Queen’s Park watched as their first team players enlisted almost en bloc.Whilst there wasn´t a mass exodus from Celtic, a number of players did enlist and sadly, some failed to return.

Willie Angus, John McLaughlin, Archie McMillan, Leigh Roose, Donnie McLeod, Robert Craig and Peter Johnstone all played on the field of Celtic Park and fought in the Great War and for their lives in the fields of France and Belguim.

The story of Willie Angus, a reserve team player at Celtic Park is quite astounding. Angus was awarded the Victoria Cross in 1915 for his incredible bravery in rescuing his wounded commanding officer.

Despite coming under heavy fire in ´no man´s land´ near Givenchy in France, Angus risked his own life and was wounded over 40 times in the process.

As a result of the injuries he sustained Angus lost one eye and was invalided out of the army. On his return he maintained a close affinity to the Club and his bravery was officially acknowledged when a street in Carluke was named in his honour.

Welsh International goalkeeper Leigh Richmond Roose came to Celtic Park on loan from Sunderland in March of 1910. Securing his services at Celtic was the result of a somewhat bizarre deal.

Roose had tended the goal for the Wales v Scotland International at Rugby Park the previous week in a match which led to Jimmy McMenemy being injured as a result of some nasty play by Welshman Llewellyn Davies.

Thus when Celtic keeper Davy Adams was floored with pneumonia for the Scottish Cup semi against Clyde, it made perfect sense to secure the services of Roose as a form of compensation.

Unfortunately Roose, who was a doctor of bacteriology, failed to keep a clean sheet for his one appearance and Celtic lost the tie 3-1.

Roose was an extremely wealthy man, and a gentleman. Indeed, he apparently ran the length of the pitch to congratulate and shake the hand of the Clyde player who had scored the third goal and ousted Celtic out of the Cup.

Roose went on to play for Aston Villa and Arsenal before joining the 9th Royal Fusiliers in 1914. His repeated bravery led to the Military Medal in 1914. Sadly during the Battle for Montauban where hundreds lost their lives, Roose was pronounced missing in action, presumed dead on the 7th of October 1917. A dedication to his memory is inscribed on the Thiepval memorial.

Donnie McLeod signed for Celtic from Stenhousemuir on May 10, 1902. McLeod, dubbed ´Slasher´ due to his sheer speed and ability was a two-footed full back who was an instant hit with the Celtic support.

McLeod was an integral part of the side who kick-started the club´s unprecedented feat of six Championships in a row from 1904, and during his six-and-a-half years with the Celts he made 155 appearances.

McLeod´s partnership with Jimmy Weir was invincible and when he was transferred to Middlesborough in 1910 Weir followed him South to form a duo described as ´the most dogged, dour and fearless pair of backs in England.´

McLeod was in the 466th Battery of the 65th Royal Field Artillery and died in Belgium from injuries sustained in action on the 6th of October 1917. He is buried in the Dozinghem military cemetery in Poperinge in Belgium.

When Robert Craig arrived at Celtic Park he was the butt of a practical joke initiated by his new team mates. Signed from Vale of Garnock Strollers on the 10th of May 1906, Craig was convinced by his team mates that a large signing on fee was available and all he had to do was ask the rather stern Willie Maley.

Maley must have liked him as his petulance was rewarded with the acceptance of his signature and a three-year career with the Celts.

Craig spent most of his period farmed out on loan but did the business when it was required and in 13 first team appearances conducted himself well. Craig was recruited to the 5th Battalion of the South Wales Borderers and was wounded during a German attack on the town of Messines in Belgium.

He died from the injuries he sustained eight days later on April 19, 1918. He is buried in the Boulogne Eastern Cemetery.

Probably the best known Celt to have fallen in the Great War is centre-half and utility man, Peter Johnstone, who signed for Celtic on January 9, 1908. Johnstone made his debut in April the following year, the first appearance of 233 for the club. During this period Johnstone scored 19 goals.

Johnstone, a miner signed from Glencraig Celtic, was an idol of the Celtic faithful and was a deserved recipient of such accolade when he lifted his first Scottish Cup medal after the final with Clyde in 1912. In the same year he added another gong to his collection when Celtic met and beat Clyde in the Charity Cup final in an amazing tie that Celtic won by 7 corners to nil.

Johnstone was part of the infamous side who contested for the ´missing´ Ferencvaros Cup in Budapest against Burnley in 1914.

The game ended in a draw and it was reluctantly agreed that a return would be played in Burnley. Celtic won and the trophy never materialised but compensation was afforded to Johnstone and his team mates when they secured the Double in 1914.

Johnstone was eager to transfer from the field of play to the field of War, and was recruited to firstly the 14th Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in 1916 and latterly the 6th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders. He initiated this move in order to secure quicker passage to the Front. Whilst eager to defend his country.

Johnstone was also always willing to assist the Celts and during his army training he travelled overnight from England to help his team-mates oust Rangers from the Glasgow Cup on September 23, 1916.

To the absolute shock of the Celtic faithful Johnstone lost his life during the Battle of Arras which was fought on the 15-16th of May 1917. A Celtic Legend, Johnstone´s death was a huge loss to Celtic Football Club. A dedication to his memory is inscribed on Bay 8 of the Arras Memorial in the Fauborg d´Amiens Cemetery.

Celtic´s reserve side was also depleted due to the impact of the Great War and the following players also lost their lives. The list is not exhaustive.

Reserve team player John McLaughlin, whose previous career spanned periods with Mossend, Hibs and Renton was killed in action on May 10, 1917. McLaughlin, who served in the 11th Battalion of the Highland Light Infantry, is buried in the Etaples Military Cemetery.

Fellow reserve player Archie McMillan died of his injuries between the period of the 21st and the 23rd of November of the same year during an attempt to capture the village of Fontaine Notre-Dame in Northern France.

McMillan andeight of his regiment lost their lives in what was a successful mission. He is buried in the Rocquigny-Equancort Rd British Cemetery, Manancourt. On this day, where pausing for reflection is the tradition, we should perhaps take a few moments to remember the Celtic legends who were so greatly affected by the horror of war.

Celtic & the Xmas Truce of 1914

On Ian McCallum – WW1 & Celtic

David Sleight with A Celtic State of Mind – Fact, Fiction and Fraserburgh: it’s a Grand Old Team to play for

On Friday, 2 August, 2019 / Football / Leave a comment

As I was walking down the lane

I was feeling fine and larky oh

A recruiting sergeant said to me

Wouldn’t you look fine in khaki oh?

For the King he is in need of men

Come read this proclamation oh

And a life in Flanders for you then

Will be a fine vacation oh

The above lines from the song “Recruiting Sergeant” reflect, perhaps, the perception that many Celtic fans today have of the attitude of the Glasgow Irish towards Britain’s participation in World War One (the “Great War”) – a period that witnessed tumultuous events on both sides of the Irish Sea.

And so it was an education to listen to Ian McCallum last week on the “A Celtic State Of Mind” Podcast. McCallum has so far written, published and distributed (!) three books of what will eventually be a quite magnificent six volume history of “The Celtic, the Glasgow Irish and the Great War”. The series sets out to tell the story of the Irish community in Glasgow and their support for and attitudes towards the British war effort over the course of WW1. It truly is the definitive account of that particular passage of history and one that has Celtic Football Club running as a constant thread throughout. The fourth book in the series – “The Blood Sacrifice” – is due to be published very shortly. I can’t wait.

McCallum talks of the very significant drop in attendances at Celtic Park during the early years of the Great War (90000 in season 1914/15 alone) as Celtic supporters enlisted. These supporters were volunteers – conscription was not introduced until 1916.

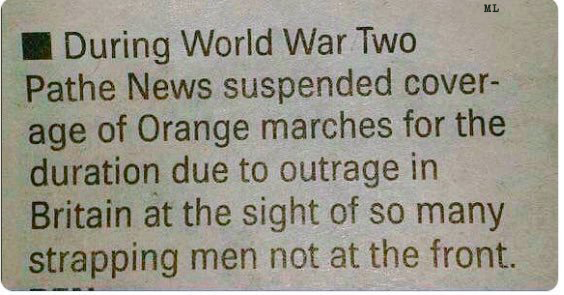

McCallum goes on to explain the extraordinarily difficult circumstances in which the Celtic team was forced to play during WW1. Football was cancelled in England but the Scottish League made the decision to play on. McCallum details how the Celtic players, in common with those at other clubs, had to accept a massive wage cut and return to their former trades while turning out for the team on a Saturday. In doing so, he dispels the myth that Willie Maley found “safe” jobs for his players during the war; the Celtic players were treated no differently to those elsewhere. Some received white feathers by way of thanks; it must have been horrendous.

And yet that Celtic team won ten league titles, five Scottish Cups, eight Charity Cups and nine Glasgow FA Cups (these latter tournaments were no small affairs, attracting huge galleries) during the period from 1905 to 1917. The Celtic sides of that era included some of the greatest Celts of all time: Patsy Gallacher, Jimmy Quinn, Jimmy McMenemy, Sunny Jim Young, Jimmy “The Sniper” McColl and the man they called “The Icicle” – Alec McNair. Between the sticks was Charlie Shaw (256 shut outs in 492 appearances) and at centre half was Peter Johnstone.

Johnstone was the most famous Celt and, arguably, the most high profile British footballer killed during the Great War. He spent the first two years of the conflict down a mine, emerging to play for the Hoops on a Saturday, but joined the army in 1916 and was blown to smithereens at Arras the following year. He has no known grave. McCallum explains that rivalries were set aside as news of his death filtered back home. “Glasgow fell silent”, he says.

McCallum also debunks the notion that Celtic should today surrender the 1914/15 league title to Hearts on the basis that Celtic pipped Hearts to the title that season and that many of the Hearts first teamers were part of George McCrae’s Battalion (also known as the 16th Battalion, the Royal Scots). Their participation and that of players from other teams in the East, including Hibernian, ensured that within a week McCrae had 1350 men – a phenomenal effort. McCallum explains that many of the Hearts players never actually left Edinburgh but were involved in “military training” and available to play on a Saturday – not very different, perhaps, from the lot of the Celtic players employed in “war related” work for twelve hours a day from Monday to Friday.

With Celtic having no game on Saturday, I listened to the ACSOM podcast en route to Fraserburgh for a Highland League match between the local side, known as “The Broch”, and Wick Academy. Why? Why not? Daniel Gray, in the latest edition of The Nutmeg (the excellent Scottish Football Quarterly) describes the Highland League as almost a footballing idyll, one “providing a glimpse of everything the game can be”.

I know what he means: this is senior football and as hard and unyielding as the granite of the houses that surround Fraserburgh’s Bellslea Park as it clings to the coast in this most north easterly corner of Aberdeenshire. But it is also an incredibly friendly league and one where loyalties run deep. It is not at all unusual for players to play for the same team for a decade or more; all but one of the Wick first team live in Wick or neighbouring Thurso.

I wrote last time of the match that Celtic played against Liverpool in April 1989 to facilitate the Reds’ return to football after Hillsborough. And there in the Fraserburgh board room was another reminder of why Celtic is such a special club: proudly displayed next to the bar is a poster for the match that Celtic played against Fraserburgh at Bellslea on 28th April 1970 – just a week or so before the small matter of the European Cup Final in Milan!

But Celtic were in Fraserburgh for a very worthy cause: the match was played to raise funds for the families of the five men who perished in the Fraserburgh Life Boat disaster in January of that year (the third such disaster to afflict Fraserburgh in the twentieth century).

And this was no Celtic second string that was sent north. Alongside the match poster is a picture of the two teams lining up side by side before the game. The ruddy, wind-swept faces of Murdoch, McNeil, Lennox, Wallace, Auld, Craig, Hay, Johnston and Hughes stare back at me. Celtic means different things to different people but we can be proud of our history for more reasons than one. It really is a grand old team to play for…

![[Untitled] [Untitled]](https://wikifoundryimages.s3.amazonaws.com/5953998c4748723cee070e35b1a19eba)