The War Years | Celtic Games | Tournaments | Honours

Celtic during World War Two

This section is for all the events which affected Celtic (fans, players and staff) during World War Two.

Rest in Peace to all those who died and our sympathies to all those who lost loved ones through those difficult years.

First Team Manager

- Jimmy McStay (Celtic Manager 1940-45)

Players

Celtic lost players and staff to the war effort (both voluntary and due to the call-up).

Players & other staff members from Celtic to have served/enlisted (both those playing to have signed up or have previously played for the first team):

- Seton Airlie (Army)

- Oliver Anderson (Royal Artillery)

- Alec Boden (Army and a Physical Training instructor, became a Sergeant)

- Joseph Leo Coen (RAF)

- William Corbett (Royal Navy)

- Tom Doyle (Forces)

- Robert Duffy (RAF)

- Cornelius Ferguson (RAF)

- Willie Gallacher (Royal Engineers)

- John Hunter (Navy)

- Willie Lyon (Scots Guard)

- Henry McCluskey (Royal Engineers)

- Joseph McCulloch (Royal Scots Fusilliers)

- Patrick McDonald (Royal Navy)

- John Reid McKay (Army)

- Roy Milne (RAF)

- George Paterson (RAF)

- John Paton (RAF)

- Joseph Rae (Royal Navy)

- James Shields (RAF)

- William Waddell (Army)

- John Watters (Navy)

(If there’s any missing staff/players in the above then please contact us to add them to the above).

Notable supporters

- James Maley (Spanish Civil War veteran)

- James Stokes (awarded Victoria Cross for bravery)

Celtic in World War Two

The Second World War was a catastrophic period that left a permanent scar on communities globally. In Scotland, the impact as elsewhere was massive with air bombings by the Axis powers bringing the battle to the homes of the soldiers as much as on the battlefields themselves.

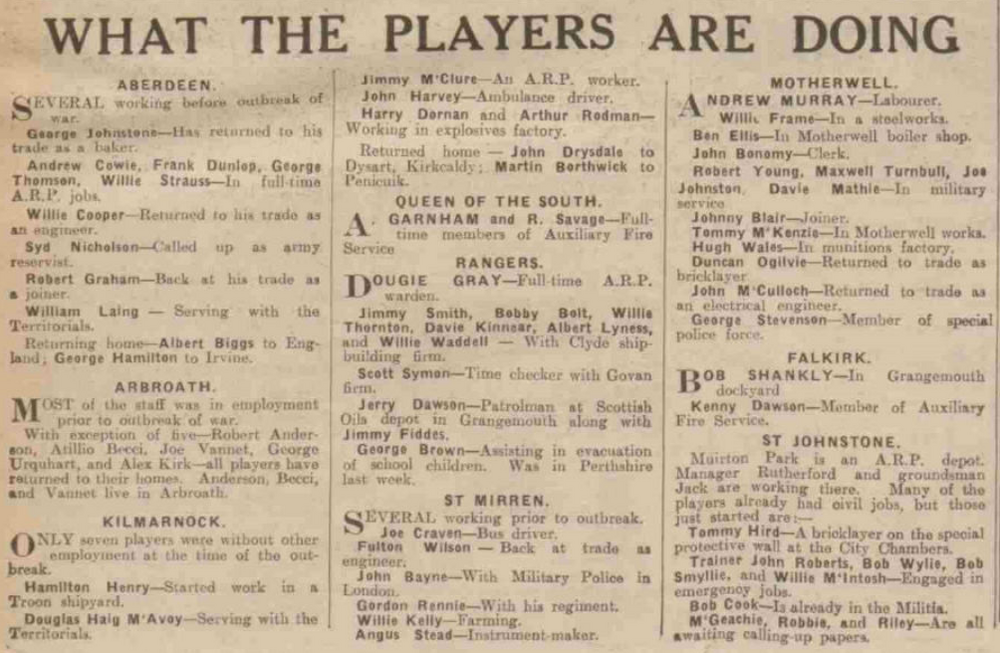

As for Scottish Football and Celtic, inevitably it was to be heavily impacted as well. An edict was released after the declaration of WW2 that all forms of mass entertainment (including football) were to be abandoned. In time, this was relaxed but a revised league set-up was brought in with separate West and East leagues to lower travel and costs, Celtic playing in the 16 team West Regional League. This lasted for just one season before an SFA suspension on the league led to a ‘Southern Scottish League‘ being set-up, and a parallel one for the north. As for the cups, the Glasgow and Charity Cups still carried on. Other competitions picked up or began later on (such as the Regional League Cup).

Out of a sense of community duty, Celtic lost both players and staff to the war effort (both voluntary and due to the call-up). Those who left Celtic (and other ex-Celts) to enlist included the men as listed on this page.

Add to this the number of young men sent to war who could have been given a chance at the club, and you can only now imagine the impact it was to have on society & the club. Others who remained at home, such as John Morrison, had to leave their roles with Celtic partly due to the difficulty of balancing playing for Celtic with their wartime roles (e.g. working down the mines etc). John Divers used to turn up at Celtic in his shipyard overalls after a hard day’s slog, and Celtic was never going to be able to take priority for them in these circumstances.

The Celtic Board didn’t exactly help by steadfastly refusing to pick players from the forces stationed in Scotland (as was allowed). For example, Stanley Matthews is one of the most lauded players of all time, and he played for Morton. An important loss was that of Celtic-mad Matt Busby, who made himself available to Celtic (as he was a big Celtic fan from Lanarkshire) when he was stationed in Scotland (at the time he was a top level player with Liverpool). Whatever the reason why he wasn’t taken on (e.g. unwilling/unable to pay inducements?), Celtic lost a quality player when we really needed one. Matt Busby himself said the spent three years in Scotland hoping to get the call to play for Celtic. It was ridiculous by the board.

Restrictions on crowd sizes and wages impinged on any club ambitions, and it was supposedly not the time to be planning for growth of the club. Yet others did, and Rangers in particular took much advantage of the circumstances to dominate the league and cup competitions. Despite the circumstances, to keep morale high across communities, there were still near enough full match programmes ongoing through these war years.

Celtic’s Playing Record

Frustratingly, Celtic’s playing record during these years was pretty poor. Most clubs (especially the smaller clubs) suffered badly from loss of local manpower and revenue, whilst certain establishment clubs were less impacted. Celtic as a larger club were able to draw in from a larger local pool but were unable to compete with Rangers who dominated the period partly due to favours from certain sections especially from the shipyards.

Most often, the Celtic manager wasn’t certain who could play due to the war effort and work until closer to kick-off, and explains why there were so many players over this period who played only a few or even just a single time for the first team.

However, in truth the management structure behind Celtic is much to blame for this as well. After 41 years of management by Willie Maley, former player Jimmy McStay was brought in from Alloa as manager in 1940. To summarise the attitude of the board towards Jimmy McStay, Bob Kelly (then a Celtic director) later described him as being a “part-time manager” and that Jimmy McGrory was really ear-marked for the role. Charming!

The Celtic board basically pulled the strings on team selection and treated Jimmy McStay dismissively. In effect, the board were a pale shadow of the forward thinking and practical men who had built Celtic in its early years, but rather now were just smug grandees of a venerable but decaying institution. Back slapping and self-congratulations (whatever for?) were the order of the day for Celtic’s directors, or just sticking their heads in the sand. You could add that the club’s own directors had a seeming indifference to Celtic’s performances in wartime football. This was demoralising for any player or manager, as what were they then playing for?

The squad was depleted not only due to the war, but also from the loss of some great players who could have stayed on such as John Morrison to Morton. Many a time Jimmy McStay had to patch together a side taking players from junior teams just to be able to get a full side on the pitch. There were some highlights, with Celtic signing a young Willie Miller and John McPhail and in 1944 Bobby Evans, all of whom in time became great players for the club.

The first season was a disaster with countless defeats, and Celtic’s remaining end-of-season league positions throughout the war years were generally poor, although the first team recovered to come second in two seasons towards the end. In light of that this was against opposition with limited resources, some of whom were in a worse state then even Celtic’s, then this was a collapse for the club. Must add that many other strong teams weren’t even in this league but playing in the parallel North-East League such as Aberdeen, Dundee Utd, Dunfermline etc. So most likely if the full league was in play then Celtic would have been pushed even lower down the tables.

| Season | League | Position |

| 1939-40 | West Regional League | 13th |

| 1940-41 | Southern League | 5th |

| 1941-42 | Southern League | 3rd |

| 1942-43 | Southern League | 9th |

| 1943-44 | Southern League | 2nd |

| 1944-45 | Southern League | 2nd |

| 1945-46 | Southern League | 4th |

Possibly, a better barometer to gauge Celtic’s ability was the performances in the cups, and that again was poor. In this truncated Scottish set up, Celtic only won two peripheral trophies in six years, the Glasgow Cup (1940) and the Charity Cup (1943) and both of them were against limited opposition. Rangers ran away with everything as their arch-disciplinarian (Bill Struth) pushed his weight about, their most dominant era until the early 1990’s. Another measure for Celtic was that in 25 games against Rangers, Celtic only came out on top in four matches against them. Says it all really, Celtic had sunk.

Limited access to resources is a point that restricted Celtic, but that was the same if not worse for certain other teams, and there were clubs in towns with far more limited financial resources and connections upending Celtic during these years. For example, Queen of the South finished second in 1939-40 and Morton were second in 1942-43.

The lowest point during these barren days came after a game against Rangers in 1941 at Ibrox, where after a disputed penalty decision, Rangers players surrounded and hounded the referee. This led to trouble brewing at the Celtic end terracing of the stadium. The authorities as punishment shut Celtic Park down for a whole month! They harked back to a meeting agreement back in 1922 (which was chaired by Celtic grandees). However, Rangers’ were censured by the SFA but were lightly treated in comparison to Celtic. It was an excessive punishment and a nonsense, but due to wartime it was difficult to escalate the matter and Celtic were further hampered.

Rangers and their sympathisers simply had their hands on the controls and nothing was to get in their way. It helped them that they pulled strings that the bulk of their players got jobs in the local shipyards to avoid signing up for front line duty. One Rangers player even sued the Sunday Mail newspaper after having described him as a “draft dodger”.

The manager never really had a sniff at the team selection, and was treated more in an honorary position even though on accepting the job he was told he would have full control. Basically, Jimmy McStay was on a hiding to nothing. His problem ultimately was he was too much of a gentlemanly character. Sadly, he was made to carry the can for Celtic’s decline by the board, and at the end of the war he was dismissed in preference for Jimmy McGrory.

Disgracefully, Jimmy McStay found out about his dismissal through the press whilst on holiday. A great old stalwart like Jimmy McStay deserved better treatment. He was possibly not the right man for the job, yet if he wasn’t fully responsible for team selection then shouldn’t those who did (e.g. the board) not also step down? Not the last time the Celtic board had not realised the irony of their decision-making.

Any high points? Fans still turned out in their numbers. Showed just how important Celtic was to the long suffering community that fans still came to watch what was then a club in decline. Apart from that, not much good sadly.

One match reporter, Alan Breck of the Evening Times, caustically wrote after a 2-0 victory over Queen’s Park in 1944:

“I have never seen a Celtic team that depended so little on the arts of inside-forward play… these present-day Celts have no ball-play or combination… they beat a man by holding or pushing… I hope – with peace just around the corner – the Celtic people realise how much they have to do.”

Post-War

When the war ended in 1945, it was time for the country to rebuild, and that very much included Celtic. The War Years ended up marking a poor time for the club not just on the field but in particular its board management as well.

Post-war, Celtic continued to suffer with Rangers carrying on strongly having come out comfortably well from the war. Give or take a few bright spots, such as the wonderful league & cup double in 1953-54, it was not really until Jock Stein’s return in the 1960’s that Celtic finally regained its glory days.

One final notable event was the ‘Victory In Europe‘ trophy. To celebrate the end of hostilities on the European continent, in 1945 the Glasgow Charity Cup committee presented the ‘Victory in Europe‘ Cup which would be awarded to the winners of a charity cup final. Rangers were invited to participate but declined as they had a forthcoming cup tie against Motherwell (how patriotic of them). This allowed Queens Park to step in and play Celtic in the match which Celtic were to go on to win by one more corner kick. A bizarre ending to a difficult time for all.

However, the difficulties didn’t end there. In 1946, Celtic played Rangers in the final of the Victory Cup (a one-off summer tournament). The match was a travesty with the referee biased and blatantly giving Rangers decisions. The referee was believed to also be tipsy. This caused a furore, the sending off of George Paterson and then further havoc. It led to a disgraceful heavy punishment for Celtic’s George Paterson as Celtic Chairman Bob Kelly recalled:

“The most unfair punishment ever meted out by the referees committee was to George Paterson. The cruelty of his sentence was shattering to both player and club“.

It sadly was to set the tone for Celtic for the post-war period.

Quotes

“Rangers might not want favours from referees, but they certainly get them.”

Journalist Bob Crampsey citing a Daily Record columnist

“They keep talking about it now when it comes to the attendances they are getting , but when you go way back to 1945 there was nothing, you couldn’t do anything, there was nowhere for people to go. Every away game other than Ibrox the gates were closed for the game. Ibrox held something like 120,000 at the time so that was the only away game that the gates weren’t closed. It was a good time and believe it or not I got £2 per week with ten bob off for income tax, thirty shillings players were getting for playing in the first team. Players like Malky MacDonald. Willie Miller, Johnny Crum, George Paterson , it’s amazing really but that’s what they were getting as well.”

Bobby Evans

League

League Table 1939-40

League Table 1940-41

League Table 1941-42

League Table 1942-43

League Table 1943-44

League Table 1944-45

League Table 1945-46

>>League Table 1946-47

Tournaments

Books

Songs

From “Not The View” Fanzine

Note: Above says “Divers: did a bunk to Ireland”. From our records, this is untrue. From our records, John Divers continued to play for the Bhoys during the regional competitions of the war years but would turn up at Celtic Park in overalls having come straight from a hard shift in his war job at the shipyard. He played for Celtic throughout the war (with a loan spell at Morton).

Articles

Rangers dominated wartime football but should their titles be recognised in the record books?

Football’s last big shutdown is still sparking debate

By Andrew Smith (note: Andrew Smith is ex-Celtic View editor)

Saturday, 21st March 2020, 8:57 pm

https://www.scotsman.com/sport/football/celtic/rangers-dominated-wartime-football-should-their-titles-be-recognised-record-books-2504693

However Scottish football is reassembled when the coronavirus pandemic does eventually subside, decisions taken over how to settle the outstanding issues of the 2019-20 campaign will be inevitably subject to feverish debate.

And if any proof were required as to the ceaseless arguments that can ensue from global events shutting down football, a petition started in 2017 might be a decent starting point. It came from a Rangers supporter who called on the Scottish football authorities to recognise the 12 trophies the Ibrox club won during the years of the Second World War when no official football competitions ran.

The desire of this fan to have his club “going for 61” doesn’t quite equate with the form of the game that did ensue from Britain declaring war on Germany on 3 September, 1939. A mere day after a full card in the Scottish League – the fifth round of matches in that aborted season – concluded with clubs that had travelled distances to play dashing home in order to beat the first night of the blackout.

The fact the blackout of football lasted fewer than two months is indicative of the hold the game held over the nation – and the government’s assessment as to the purpose it could serve. It was considered games would boost morale and prevent boredom setting in which, it was feared, could give way to social disorder.

The football played in the war years across this country – the Scottish League suspended any tournaments under its direct auspice until 1946-47, the end of hostilities in 1945 coming too late for a normal league format then to reintroduced – was chronicled with typical flair and forensic focus by peerless game historian Bob Crampsey in his centenary history of the Scottish Football League.

What he picks apart is not the sport as we know it, or as existed before Germany invaded Poland. It is a period of ever-changing league formats and star-embossed teams courtesy of stellar English-based players stationed in Scotland – the likes of Matt Busby, Stanley Matthews, Tommy Lawton and Frank Swift – guesting for clubs, and a dominance by Rangers that they would only enjoy again in the 1990s. A dominance helped, not so much by their players finding reserved employment in the shipyards as is still grumbled over, but weak refereeing. On the latter matter, Crampsey cites a Daily Record columnist who was moved to declare: “Rangers might not want favours from referees, but they certainly get them.”

Yet the Ibrox club were the true architects of their own success. Driven by über-manager Bill Struth’s belief that it was a patriot’s duty to deliver footballing entertainment during a time of strife, their attitude to wartime football contrasted with Celtic’s. A complete irrelevance during this period, the east end of Glasgow club were rudderless after jettisoning the godfather figure of Willie Maley. His three-decade, 30 major trophy managerial career was ended against his wishes during the first war league. Celtic were further hampered by their unique refusal to play guest players, losing Celtic-daft Busby to Hibernian as a result.

The initial league set-ups established in September 1939 were curious in their parameters. The desire not to have clubs travelling far because of transport and safety issues led to the formation of regional West and East leagues, each with 16 teams. That meant teams being set aside. Brechin City, Forfar Athletic, Edinburgh City, Leith Athletic and East Stirling were the unfortunates. It was decided two of the smaller Edinburgh clubs had to give up a senior league presence and Leith lost out to St Bernards on the toss of a coin.

Separating east from west meant Hearts, Hibs and Aberdeen being detatched from Glasgow’s big two and their gate receipts. The decisions resulted in the Tynecastle club immediately expressing concerns over their ability to remain solvent. Sound familiar? That came even as the SFA declared all players’ contracts void only three days after the country had entered the war.

Scotland did become a mecca for guests, though, because the maximum wage of £2 per week was almost double that on offer from the English game, at least until 1943.

Crowds for the 1939-40 campaign, as it was, weren’t sufficient to prevent most clubs losing money, Celtic posting the biggest losses. Only three clubs made a profit, Rangers foremost among them. Much has been made of the Ibrox club retaining their players while such as Hibs, with 30, and Motherwell, who had 13, delivered many men to the front. Celtic supporters of a certain vintage will argue blind their club lost many influential players in contrast to their ancient rivals. Yet Crampsey notes that both clubs were criticised for the “microscopic contribution” they made to the war effort in this respect. He states that, of the 22 players that were regular first-teamers immediately before the war, only two from each “ended up in uniform”. Rangers’ Willie Thornton did so with enormous distinction, earning a Military Medal for his valour in Sicily.

The disquiet of clubs in the east to the west/east format meant they rejected its continuation into the 1940-41 season. As a result, Hibs and Hearts joined the Southern League then established. It meant Aberdeen being left high and dry because then Tayside big hitters Dundee had no interest in playing wartime football, a disinclination shared by St Johnstone, who rented out Muirton Park so they couldn’t be co-opted. A northern league didn’t get off the ground at that stage even in the face of the SFA, in unprecedented fashion, stating they would cover any losses incurred by clubs. Meanwhile, Kilmarnock were placed on ice because Rugby Park was requisitioned for fuel storage by the army, who rebuilt it following the war.

Supporters started to rediscover their appetite for football as the war dragged on, and so did teams in the north. By 1941-42, a Northern League was established, with Rangers having such a big squad they fielded a reserve team in it. And won it… at least the spring version, with the autumn edition claimed by Aberdeen. Football was played 11 months of the year then.

It was during this period that guest players really began to bring colour to the Scottish game. Matthews turned out for Morton and Airdrie before playing a couple of games for Rangers. His Ibrox days produced a curious symmetry. His wife Betty was the grandchild of Tommy Vallance, sometimes known as one of the club’s “gallant pioneer” founders, despite actually joining the fledgling Rangers one year into their existence. Busby, meanwhile, proved to be a key figure in the post-war rise of Hibs, thanks to his posting with Scottish Command.

The Bellshill-born sergeant was desperate to play for Celtic but they would not drop their opposition to selecting army weekenders, and their loss proved the Leith club’s gain. The great Liverpool inside forward played 40 games in Hibs colours, a Summer Cup win over Rangers his most notable outing, Another cup final against the Ibrox men was lost on the toss of a coin after it finished goalless and the other deciding factor, corners, was a 2-2 tie. More than that, though, Busby was considered to have proved a crucial mentor to the teenage Gordon Smith. The subsequent Famous Five icon made his senior breakthrough as a trialist during the war years and, aged only 16, announced his arrivial when he scored twice to help Hibs to an 8-1 win over Rangers in May 1941.

Other oddities were seeing English international keeper Swift front up at Hamilton Accies, his Three Lions team-mate Tommy Lawton appear for Morton, Bill Shankly guest for Partick Thistle and Stan Mortensen, inset, do a decent turn for Aberdeen. To name but a few.

The desire to have such fabled performers cost St Mirren dearly, however. They were fined for illegal inducements to Everton’s Jimmy Caskie and Manchester City’s Leslie McDowall – as were the two players – and five of their seven directors received lifetime bans from football activity.

An unedifying episode – the Paisley club made a scapegoat for a transgression then common – the same could be said of the large-scale riot that came during a Rangers and Celtic game in September 1941. That led the Glasgow Lord Provost Sir Patrick Dollan to implore the chief constable – who decided upon the staging of fixtures and ground capacities – to call a halt to the teams’ meeting until after the war.

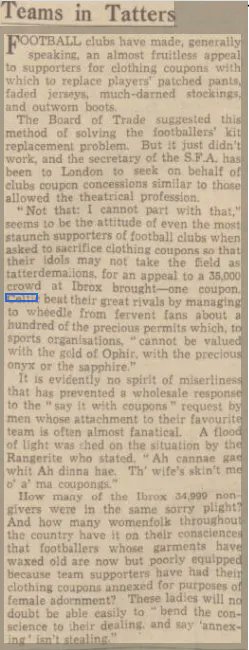

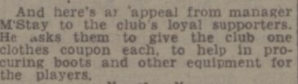

The unreal times were betrayed by the fact that a complaint to Morton by Clyde over the length of their grass in June 1941 was rebuffed with the revelation that the mower blades had been chipped by shrapnel left on the pitch following bombing days earlier. Equally, the fact that clubs were appealing to fans for their clothes coupons within the year after obtaining kit had become arduous as the result of rationing told all was so very far from normal.

Celtic would be relieved this was so after losing 8-1 to Rangers in the new year derby of 1943, the Parkhead club not even fussed about retaining players despite starting to turn a profit as crowds ramped up.

By the following season, Dundee were back in the fold following a fear that to do otherwise might result in their closure. Their jolt back to life came as a consequence of local businessmen embarking on a failed summer 1943 bid to buy Dens Park and turn it into a greyhound track.

They showed what a miss they had been by posting record attendances in the now-renamed North-Eastern League. A crowd of 15,000 turned out for a derby meeting with neighbours United.

The Rangers juggernaut continued in the Southern League and Struth’s determination to maintain standards during the war had much to do with the domination that the Ibrox club continued to hold when the Scottish League came back into being in 1946-47. Hibs and Aberdeen became their principle rivals in the immediate post-war period because they too sought to develop players and their team structures.

Scottish football’s war years did have one undoubted success, though, that can be deemed official. The desire to fill blank weekends created by the 30-game structure of the Southern League was behind the formation of the Southern League Cup. It took the form of four sections of four teams (Northern League teams weren’t allowed to compete in it until 1945-46) to decide semi-finalists. Essentially the forerunner of a League Cup that was first contested in 1946-47, the war lies behind why it remains part of the Scottish football calendar eight decades later. However, whatever petitions might be brought forth, history shows there is no rationale for placing Scottish football’s war efforts into the official record books.

Aberdeen Press and Journal:

This appeared in the Daily Record

The response by fans was poor and the Aberdeen Press and Journal blamed women for it! However in fairness, things were very tight everywhere.

Daily Record:

Willie Woodburn, the Rangers player given a life-ban for a series of violent on-field incidents ending with a head-butt, was a true Ranger in every sense. “When war broke out, Willie, like many other Rangers was fixed up with a job in the Clyde shipyards so his career was not affected” according to the Rangers News of 10 May 1972. ”

The Celtic Story during the Great War and World War Two

By Editor 14 July, 2024 No Comments

[The Celtic Story during the Great War and World War Two]

Football did not stop in war-time. In both 1914-1919 and 1939-1945 football continued to be played. There was never any total cessation during either World War.

Another look back through The Celtic Park archives to enjoy the work of legendary Celtic historian David Potter who passed away last July.

Celtic 1915-16

Let us return to football played in the difficult times of the two wars of the 20th century. There is a huge difference between Celtic’s performance in both wars – and the reason was Willie Maley.

In 1914 -19, Maley, in his late 40s was at the height of his powers, already the most important man in Scottish football with a persona and an aura about him, and he was able to ensure through his many contacts that most of his superbly talented side of 1914 were able to get jobs in the munitions industries.

Full time professional football was not allowed, and every player had to be either in the forces or in some war-related industry before he was allowed to play football on a Saturday afternoon. It was far from satisfactory, but it was better than the trenches, and Maley worked hard to keep his men out of the Army.

Odd behaviour, in some ways, for the son of a soldier, but for Maley, Celtic came first.

Maley’s hard work made sure that Celtic were able to win the League in 1915, 1916, 1917 and 1919. There was no Scottish Cup played in the War, but the Glasgow Cup and Glasgow Charity Cup continued.

The Glasgow Cup was won in 1915 and 1916, and the Glasgow Charity Cup every year other than 1919. From November 13 1915 until April 21 1917, Celtic did not lose a single game, meaning that they were undefeated in the calendar year of 1916.

In April 1916, they played two games on one day, won the pair of them and in so doing won the Scottish League. The dominance of the other teams was extraordinary.

Celtic 1916-17

World War I was, thus, a remarkable time for Celtic, and it was not that they didn’t have their problems. Peter Johnstone joined up and was killed in 1917, Patsy Gallacher was (irrationally) suspended from football for eight matches in 1916/17 for “bad timekeeping” at his job in the shipyards, Sunny Jim’s long and illustrious career came to an end after a bad injury in 1916 and several men, notably Andy McAtee and Joe Dodds were drafted into the army in the “comb-out” of 1918, even though they might have thought themselves protected against this.

There were times when players were delayed by war-time transport, and the team would have to take the field with only 9 or 10 men … but that was wartime football for you! 1918/19 was maybe in some ways their best triumph, because for much of that time, with the country at sixes and sevens in any case, there was also a pandemic going around called the “Spanish flu”. Jimmy McMenemy was a sufferer, but recovered and Celtic duly won the League.

One cannot imagine just what all this did for the supporters. The supporters had little enough to be happy about in other respects. Heavy casualties in the war, labour problems and uncertainties about relatives in Ireland were serious things to cope with, but at least their team was superb.

Maley always made sure that the results were telegraphed to the War Office so that soldiers would know the results within an hour or so, he sent footballs to men in the trenches for lulls in the fighting, and he and William Wilton of Rangers were frequently seen in Glasgow hospitals talking to wounded soldiers. Celtic also continued their admirable work for charities.

Rangers manager William Wilton

Patsy Gallacher was “the most talked about man in the trenches”, it was claimed, and it would be wrong to think that football was peripheral to war-time life. Absolutely not so! Football and the infant cinema which showed films of Charlie Chaplin were of vital importance to morale.

1939-46 was a different matter, altogether. Maley was 71 when the war started, and was ailing. He had had all sorts of depressive illnesses, was morose, curmudgeonly, anti-social and, plain and simply, just difficult and awkward. He had fallen out with the Board over having to pay income tax on an honorarium which they gave him in 1938 for 50 years’s service, and it would have been better if he had announced his resignation immediately after the Empire Exhibition Trophy of 1938.

He eventually resigned/ retired/ was sacked/ (take your own spin!) in early New Year 1940, leaving the Board to appoint Jimmy McStay as his successor, ignoring the better qualified Jimmy McMenemy.

McStay had been a great captain, and he might have been a great Manager in other circumstances, but 1940 was a bad time. Basically he was asked to fill the huge vacuum the Maley had left at a time when both Celtic FC and football itself were in turmoil – and could not do it.

Celtic manager Jimmy McStay

Rangers on the other hand did exactly what Celtic had done in the previous war. Struth was not called “ruthless Struth” for nothing, and he protected his players. Celtic were nowhere, and the only club that put up a semblance of resistance to Rangers were Hibs. Celtic suffering badly with the absence of Jimmy Delaney whose broken arm took two years to heal, and lacking any real initiative and leadership had to be content with two trophies – the Glasgow Cup of 1940 when they beat Rangers 1-0 in the final, and the Glasgow Charity Cup when they beat Third Lanark 3-0.

Against that, there was abject failure in other competitions with the 8-1 defeat by Rangers on New Year’s Day 1943 a particular low point. Sadly, in spite of the support staying with them, the depression stayed on until well after the war, until Celtic won the Scottish Cup again in 1951. Although there were a few excuses for war-time failures (they were indeed unusual times), the Board must stand condemned for the post-war gloom.

David Potter